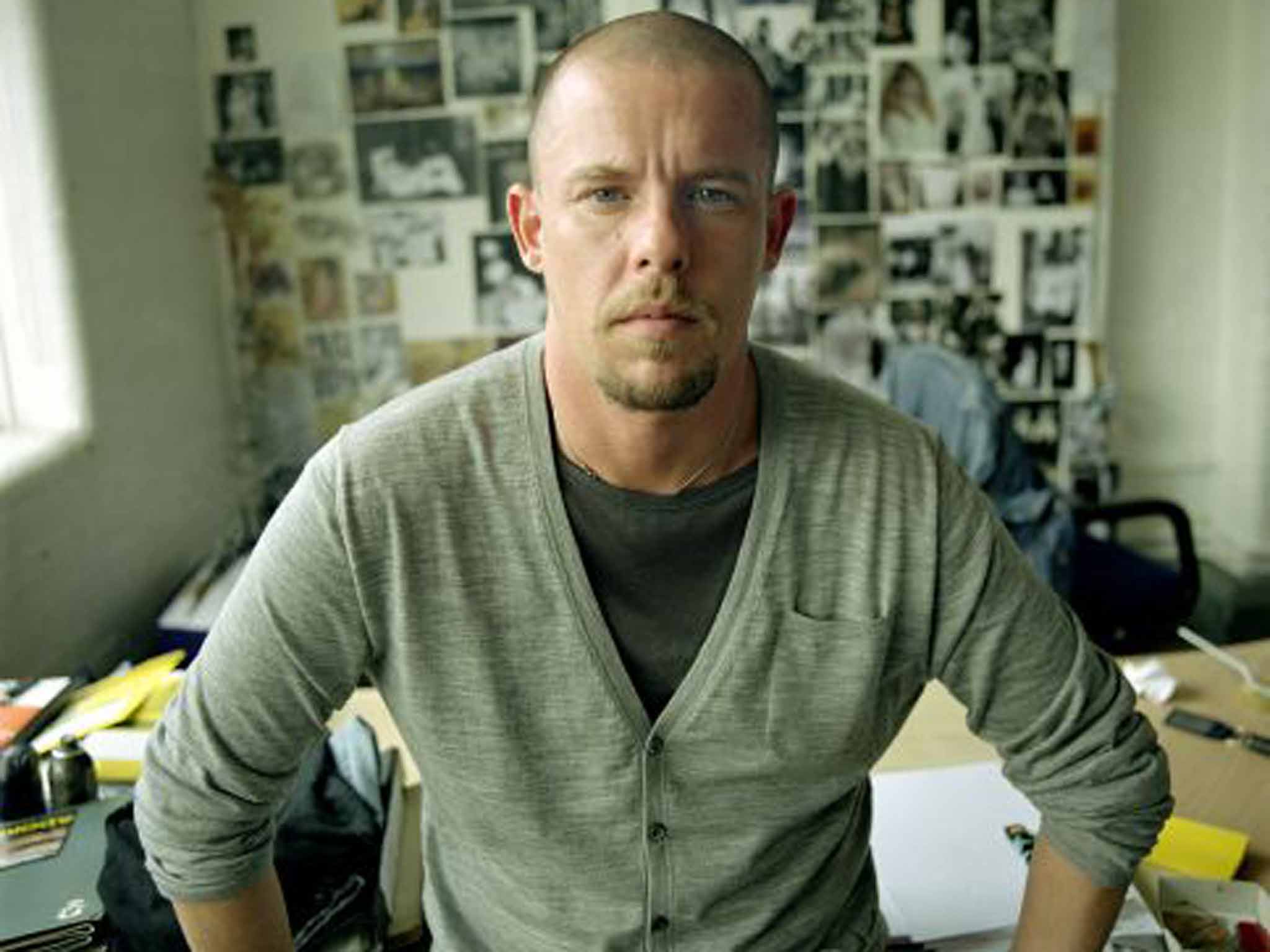

Alexander McQueen at auction: What makes a really great piece of fashion?

Rare catwalk creations by the late Alexander McQueen, including items from his controversial 1995 ‘Highland Rape’ show, go under the hammer today. Alexander Fury explains how these designs have become fashion legend

Tomorrow, a selection of Alexander McQueen garments will go under the hammer at Kerry Taylor Auctions, an auction house in Bermondsey, east London, that specialises in rare, historical clothing.

There’s something timely about this McQueen-heavy auction (there’ll be other designers’ work up for grabs, too) given that the London leg of “Savage Beauty”, the blockbuster exhibition charting the trajectory of the designer’s career, is due to open at the Victoria and Albert Museum early in 2015.

The sale collection is a micro-retrospective of sorts, spanning McQueen’s raw, early London work, through his time at Givenchy, increasing sophistication and commercial success, and on to his later Paris shows supported by the financial heft of the Kering group.

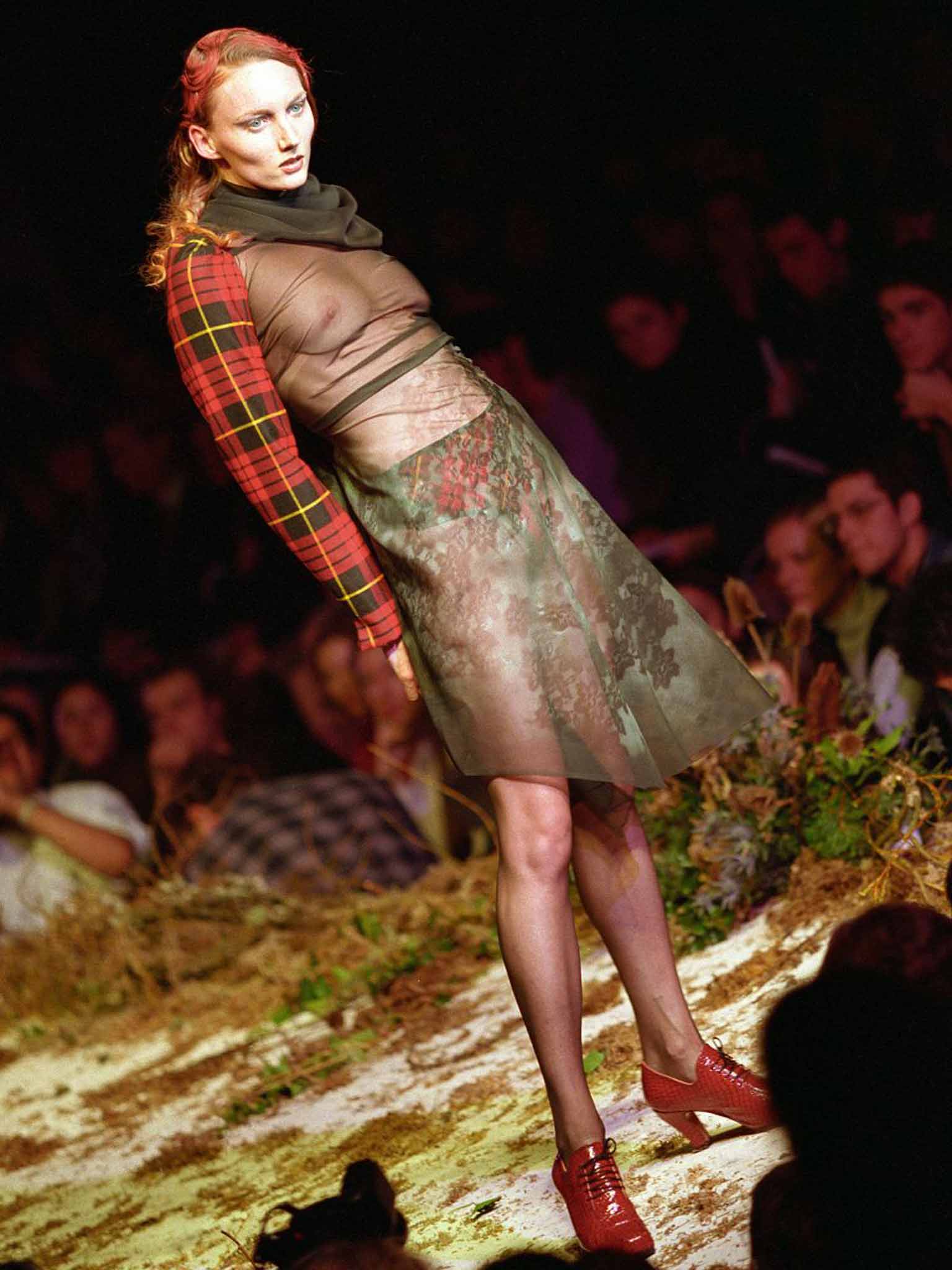

“There’s a really good cross section,” says Kerry Taylor, a former Sotheby’s auctioneer who founded her own house specialising in the sale of vintage fashion in 2003. “There things from “Highland Rape” [McQueen’s seminal and controversial collection from 1995, which despite accusations of misogyny, was inspired by England’s relationship with Scotland], the first ever bumsters… right the way through [to] beautiful haute-couture pieces from Givenchy.” And it’s all available for purchase, like the world’s greatest museum gift shop.

Taylor stages several auctions a year, but two are dubbed “Passion For Fashion” and consist of the finest examples that have crossed the threshold over the previous six months. Her buyers include numerous international museum collections, as well as private collectors, and fashion enthusiasts. Which raises questions about the reasons that people buy these clothes. To wear, or simply to have? For vanity or to covet?

Buying fashion like this is a little like buying a rare, incredibly expensive bottle of wine. Uncork it and it could taste like vinegar, as well as immediately losing all its value. So, perversely, the oenophile will keep their bottle corked, prized simply for its presence rather than for its taste. Likewise, fashion collectors may buy these garments purely for their scarcity and significance on a larger scale, rather than for the fact they’ll look good on the social circuit. That said, when I attended a quiet pre-auction viewing on Sunday, Taylor’s showroom was filled with various London vintage dealers and a well-dressed Middle Eastern couple who pawed through that Chanel and Hermès cache as well as a clutch of Azzedine Alaïa garments. Most of the items were barely three years old, and a fraction of the usual price.

Above and beyond the idea of “to wear, or not to wear”, Taylor’s wares raise more fundamental questions. Well, fundamental for those of us concerned with seam allowances and spray-starch. Namely, what makes a really great piece of fashion? What qualifies its place in the pantheon of the greats? Scarcity? The hand of the designer themselves? Or their creative vision being fully expressed, without the limitations of budget, regardless of who actually stitches the stuff? “It’s not all just in a name,” says Taylor. “It has to be a complete ensemble, it has to be from a very early rare collection. Or it just has to be beautiful – extraordinary in some way.”

So what is it that makes the McQueen pieces that Taylor is selling extraordinary, rare and historical? Well, a few of them aren’t, especially. Some are simply beautiful pieces of fashion. These include a couple of commercial variations on dresses from “Plato’s Atlantis”, the final womenswear collection shown by McQueen before his death in 2010. Said variations would have hung in stores across the world (37 directly operated stores and franchises, according to this year’s figures) and been bought by thousands of women.

They stand in marked contrast to an apparently nondescript pair of trousers. They’re narrow, made from grey suiting, sit low on the mannequin and are crudely constructed. Then there’s a plastic vinyl skirt with its hips slashed open, a busted zip and a kick-pleat that’s beginning to tear. Neither has the all-important McQueen label stitched into the waistband, nor the polish, precision or even beauty of McQueen’s later work. That’s because McQueen made them himself, on a domestic sewing machine, one-off pieces for friends or early catwalk shows that were little sold (if at all). You can’t get rarer and more historical than that.

McQueen’s work was consistently extra-ordinary – beauty, however, is in the eye of the beholder. Take the “bumster” trousers, which McQueen designed in the early 1990s. For the uninitiated, what those entailed were hipsters pushed to an extreme, a waistband falling so low on the torso that the crease of the wearer’s buttocks were exposed at the back. To McQueen, the bottom of the spine was the most erotic part of the body. The press only saw the similarity between McQueen’s design and sloppy, tugged-down trousers exposing a builder’s bum.

“They’re not pretty,” admits Taylor, speaking specifically of the trousers that she’s offering for sale today. “They’re really badly made, they’re really rough.” The trousers were made in 1992 following McQueen’s graduation from Central Saint Martins, for a friend of McQueen, a drag artist whose performance name is Ms Trixie Bellair. The pair is the prototype: McQueen borrowed them back to copy the “bumster” pattern for his first catwalk show, spring /summer 1994’s “Nihilism”. Their estimate (£800-£1,000) is incongruous given the actual quality (poor) of the garment itself. The vinyl skirt, shown on the catwalk as part of that controversial “Highland Rape” collection, is also basic. It’s been mistreated – the slashes on the hips are from the show, when the garment was opened at the sides, tugged down to sit lower on the hips. The seams were sealed closed with gaffer-tape. However, on another level the prices for these pieces seem remarkably low when compared to their importance as pieces of McQueen iconography. “I’m honoured to have them,” says Taylor. “I would hope that we would have interest from British institutions.”

Those institutions should be interested – and hopefully are – because the “bumsters,” and the selection of pieces from “Highland Rape”, are evocative of an entire period in British fashion, and culture. McQueen’s trousers were an extreme example of a low-slung waistband, later commercialised as the “hipsters” that dominated the high street and high fashion throughout the 1990s. And McQueen’s work finds a reflection in the output of the “Sensation” school of Young British Artists – his visceral fashion, which included transparent plastic bodices sandwiching tapeworms against models’ flesh are an aesthetic and conceptual counterpart to pieces by Jake and Dinos Chapman and Damien Hirst. I’m not saying these trousers are art, but they come from a similar cultural crucible.

The other items for sale are interesting for different reasons. At the viewing day I attended, potential buyers pored over the lots. It is a very different experience from the reserved, rarefied atmosphere of a museum exhibition of fashion. The majority of the garments are packed tight on rails, Chanel jostling Dior, crammed against an 18th-century frock coat and an unnamed mid-Fifties sable. The mood is halfway between a jumble sale and the wardrobe of an especially dazzling oligarch’s refined mistress. A selection of garments are showcased on mannequins – the really stellar stuff, such as a sweeping Elsa Schiaparelli coat from her 1938 “Zodiac” collection (one jacket from the same collection went for £132,000 at Taylor’s auction in May) or couture pieces by Yves Saint Laurent and Balenciaga. But even these can be manhandled off for you to twist inside out, or even try on. A number of Taylor’s customers purchase garments to wear: there’s a commercially canny selection of Chanel and Hermès handbags set to open the bidding that no museum would look at twice, but that many women would pay top dollar to own.

For her part, Taylor has always been convinced of the validity – ideologically and financially – of fashion and textiles at auction. In 1986, she re-established costume and textiles auctions at the New Bond Street saleroom of Sotheby’s – subsequently selling garments owned by Maria Callas and the Duke and Duchess of Windsor. Her auction house specialises in nothing but, and has sold garments whose prior owners include Audrey Hepburn, Elizabeth Taylor and Diana, Princess of Wales. “We’re famous for selling McQueen,” she says, of her own-name operation. “I was the first to try and sell McQueen ever at auction. I had some men’s clothing which I tried to sell when I was at Sotheby’s – probably [in] the late 1990s, or 2000.” She also sold Vivienne Westwood and John Galliano pieces, both of which also feature in today’s auction. The Galliano is a swagged frock-coat in gabardine, designed when both Galliano’s workroom and show were still based in London in the late 1980s; the Westwood includes a rare entire outfit from the designer’s 1987 “Harris Tweed” collection, complete with fabric crown. Museums and collectors alike would clamour for that.

There are, of course, those garments that any collector, and Taylor herself, would clamour for. “A Schiaparelli, from the ‘Circus’ collection,” she states, immediately. “I’d love to get a piece from Dior’s first collection… I’d love a really wonderful Poiret. I’d like something by Chanel, daywear, knitted jersey… It just goes on and on. The most valuable things are a combination of the best designer for that period, at their height; the best condition; the best example, with a label. And preferably owned by someone famous.”

That said, certain designers – such as McQueen – will always be collectable, although popularity waxes and wanes according to external circumstances. Exhibitions and label revivals cause both interest and prices to spike. “When they had the [Savage Beauty] exhibition in New York, I got £65,000 for a piece of ready-to-wear,” says Taylor, slightly incredulously. “They are so, so important.”

The issue with McQueen’s bumsters is that, for all their significance in the canon of his work, they aren’t especially spectacular. No museum could build an exhibit around them in, say, the way they could with the infamous Vivienne Westwood “super-elevated” platforms that caused Naomi Campbell to tumble at her autumn/winter 1993 show. The V&A made those a tourist attraction, selling posters featuring just the shoes.

Nevertheless, Taylor offers a simple and persuasive argument. “We won’t always have these,” she says, referring to the clothes that cemented McQueen’s reputation. “They are going to dry up. We will look back at sales catalogues like this and think ‘God, do you remember when...?’ This is an excellent time to be investing.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments