Something old, something new - the lure of historical brands for a new generation of fashion designers

Young British designers are increasingly coupling with centuries-old brands in an unlikely fusion of hitherto dusty heritage and the strikingly contemporary. It’s a mutually beneficial marriage, and proof opposites can prove very attractive, says Alexander Fury

Lately, fashion has become peopled by odd couples, strange twosomes grouped under a new favoured heading: “collaboration.” The ubiquitous conjunction for these two names is the letter “X”, a vote of confidence in the unlikely fusion of, says, a sports star with a skincare line (David Beckham x Biotherm), a pop star and a high street brand (Beyonce x Topshop), or even a television host and a preppy staple. The latter is just all-out weird, especially to British audience - Jimmy Fallon, host of American institution The Tonight Show, collaborated with J. Crew to create a pocket square-cum-phone case. Lots of cross-overs. And it’s a bit like Jonathan Ross making a line of pants with Marks and Spencer. Then again, the male model David Gandy has already done that…

Fashion designers collaborating amongst themselves has become commonplace – the newest incarnation, however, couples young brands with old in odd, May-December fashion romances, frequently with centuries separating the two. They work because they bring the best of both worlds – tradition and technique meeting innovative and experimental design. Rather than tearing down the establishment, young designers seem excited to join them, rifle through their archives, and help them create something new.

In itself, that approach isn’t so innovative – designers have been reviving moribund fashion labels for decades: Karl Lagerfeld’s spectacular resuscitation of the dusty and fusty Chanel in the eighties remains the benchmark, emulated by labels as varied as Gucci, Yves Saint Laurent and Balmain. The difference today is that it’s a two-way street, and a part-time (or even one-off) gig. Rather than being installed as creative directors, expected to revive entire labels, young designers are creating capsule collections as savvy one-hit wonders. And the brand they’re working with are esoteric and unexpected – Mackintosh, Morris & Co., traditional Savile Row tailors like Huntsman, handbag companies like Radley. Rather than the established, wide-spread dissemination of a designers’ style into a mass-market product (see Balmain x H&M, or Topshop’s collaboration with London labels like Mary Katrantzou, Christopher Kane and Marques’Almeida), it’s about intense focus of particular product areas.

Jonathan Anderson, for instance, turned to Mackintosh to create a trench coat that’s traditional in technique, but contemporary in shape.

It features idiosyncratic and utterly Andersonian design touches, like oversized, irregular horn buttons, or extended cuffs enveloping the hand. The block is Mackintosh’s, but Anderson exaggerated and adapted it. When it comes to the structure, it’s time-honoured. “We still use exactly the same technique for making a Mackintosh raincoat as we have done for almost 200 years now, so the process used for making these coats was entirely traditional,” says Mackintosh’s brand manager Sophie Wright, of the brand established in around 1830. That technique consists of two rubber-bonded layers of cotton, and hand-taped seams. Rubber is applied to the seams by finger, and then hand-rollered with tape to seal. “A coat maker trains for a minimum of 2.5 – 3 years to perfect our coat making technique,” states Wright. “It is extremely specialised and a true example of craftsmanship.”

That’s what attracted Anderson to Mackintosh - their craft. Expensive and old-school – or, indeed, just plain old. “I think that’s what kind of built the foundation of British fashion, that idea of resource, protection, of helping and trying to create something that is quite wearable in a way and very utility,” says Anderson. “ It was built on a very tailored foundation - and that doesn’t mean that we have to stay within that foundation… but I have always made sure that there is that element of tailored aspects [in our collections] with a nostalgic fabric, which is re-appropriated.”

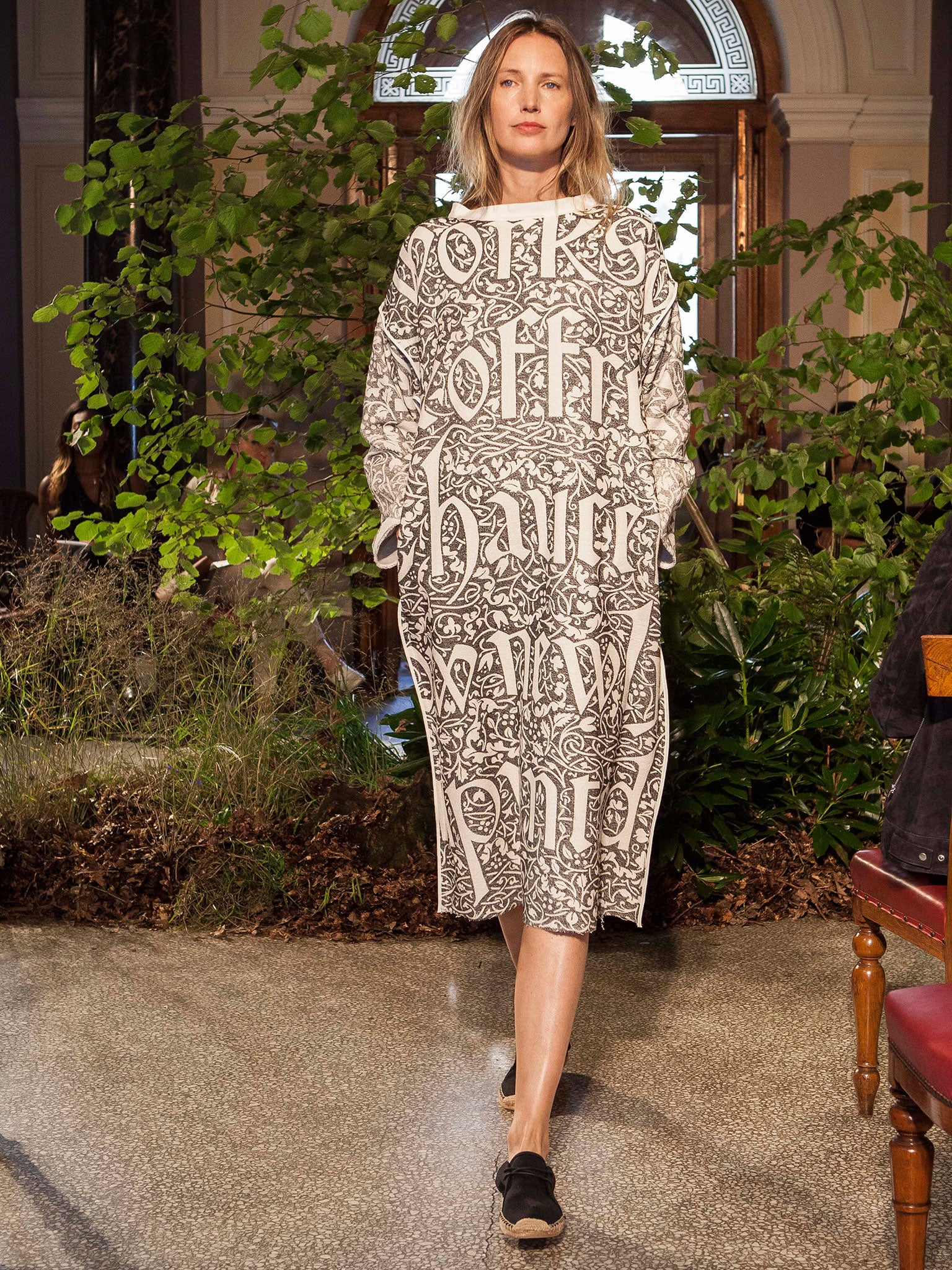

Anderson’s assertion is a succinct summary of a point of view often proffered by London designers, who turn to traditional British manufacturers, working with traditional methods, as a UK- equivalent to the techniques of haute couture. That world is rarefied, consisting of hand-made clothes produced by specialist Paris-based artisans. It’s costly and laborious – the cost due to the labour, which included workshops dedicated to such esoteric feats as bead embroidery, the dying and application of feathers, creating hand-cut and sewn imitation flowers, or complex hand-pleating. The methods used – like Mackintosh’s – go back hundreds of years. And they frequently also involve the hand, like Mackintosh’s finger-finished seams, or the William Morris prints used by young British designer Joe Richards in his spring/summer 2016 collection, pulled from the company’s archives and unchanged. “A lot of the fabrics for the collection were hand-printed in Bath, using really time-consuming techniques,” says Richards, whose collection used four Morris patterns, including a previously unseen design from Morris’ personal collection. The patterns were produced in exact scale and colour, “keeping every irregularity”. Namely – that sense of the hand.

While Paris closely guards the handwork of the haute couture – the one way of singling it out from increasingly elaborate ready-to-wear – Britain’s crafts reflect the country’s history as the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution. Hence, they’re more mechanised and less ‘unique’, but consequently more accessible. A J.W.Anderson x Mackintosh coat will set you back a hefty £1,650 – but that’s about a twentieth of the price of a piece haute couture, by conservative estimates. Britain’s equivalent of couture is Savile Row’s bespoke tailoring, which designers frequently turn to in order to imbue their clothes with added clout. Christopher Kane has collaborated with Norton and Sons on tailored womenswear coats, while in 2012 Alexander McQueen launched a one-off bespoke range with Huntsman to inaugurate the opening of McQueen’s menswear store on ‘The Row. The cost would be around £4,000-£5,000 for a suit, custom-made to your unique measurements and using techniques that – you guessed it – date back to the mid-nineteenth century, or further.

It’s not just about technique. The coupling of a young designer with a traditional brand is mutually beneficial. For the fledglings, there’s the immediate recognition of a name like Mackintosh or Morris – Richards was only six seasons into his own label when he collaborated with Morris & Co. for spring 2016, while the Morris company was founded in 1861. Moreover, the latter’s literal aesthetic imprint is plastered across millions of walls and sofas throughout the world – “making a dress look like a sofa cover did not interest me,” says Richards, but the familiarity of consumers with the patterns, and the name, undoubtedly drove both press and buyer interest.

On the flip-side, for the establishment there’s the frisson of the new, and a challenge to working practices that are often set in their ways. That’s even true of newer “establishment” labels – the handbag brand Radley, for instance, was only founded in 1998, but their techniques are rooted in age-old leather-working traditions. A collection with Jonathan Saunders – newly-appointed chief creative officer of Diane von Furstenberg – was a “reinterpretation” of heritage Radley styles, shapes and materials, according to the brand’s design director Natalie Bolton. “Jonathan opened us up to a whole new audience who may not have necessarily looked at us before.”

Broadening horizons is a key notion for both sides of the equation. These collaborations also enable designers to offer new products to excite consumers (and entice them to buy) without adding additional lines, weakening their aesthetic with multiple collections, or cheapening the brand. Indeed, Anderson’s Mackintosh mackintoshes retail for at least as much – possibly more – than his mainline creations; and Richard’s “Minimal Morris” was the theme of his entire spring/summer 2016 collection. As a new breed of collaboration, these marriages of old-school and new-wave are particularly satisfying, for the designers and brands involved, for the press to protelyse over, and, of course, for the consumer to buy. Who are, after all, the point of the whole damn thing.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments