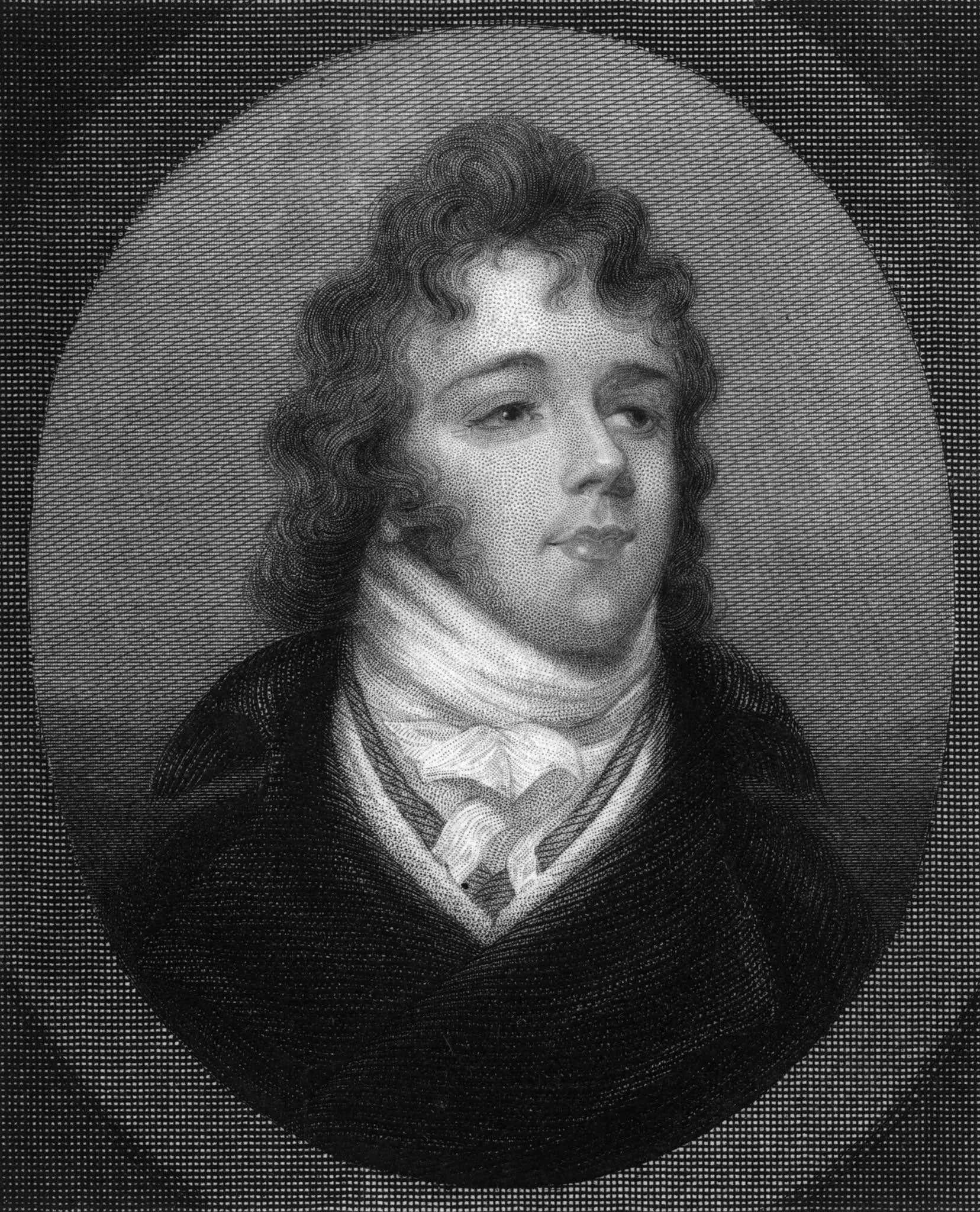

The Beau tie: Stylish Mr Brummell nailed neckwear for men

Plenty of stylish gentlefolk have contributed bons mots to the world of fashion. Throwaway phrases, mostly. Often apocryphal. Marie Antoinette never said "Let them eat cake", but the sly suitability of said saying, given her reputation for prodigious profligacy and flour-powdered poufed hairstyles, means it resonated in the popular consciousness.

But the name of one well-dressed gentleman, Beau Brummell, has become, in itself, part of the fashion lingo. They are bywords for masculine elegance, a scrupulous approach to sartorial presentation.

Brummell's approach to dress is often misinterpreted today as flamboyance, as is the notion of the dandy. Charles Baudelaire characterised the dandy as "the black prince of elegance", his attire noticeable not for its flamboyance but its perfection. As Brummell himself stated, "If John Bull turns round to look after you, you are not well dressed; but either too stiff, too tight, or too fashionable".

He was born George Bryan Brummell into a middle-class family in 1778: his father, a politician, aspired for Brummell to become a gentleman. Despite his humble beginnings, 'Beau' achieved just that. A friendship with the Prince of Wales, 'the first gentleman of England', assured Brummell's influence. His rise, coinciding as it did with the fall of the French Bourbon monarchy and a new sobriety in masculine dress, ushered in a new male aesthetic ideal. He quickly became the go-to oracle for fashionable fellows, the GQ&A of his time.

Brummell's trademark dark tailored coat, skin-tight nankeen breeches and highly-polished boots (said to be polished with champagne) were topped with a crisp, immaculately-starched cravat. Brummell spent five hours dressing each day, and gave the cravat his special attention. Once, a visitor observed piles of twisted cloth on the floor of Brummell's dressing room. Asking what they were, Brummell's valet wearily observed, "Those, sir, are our failures". They must have rankled Brummell, who once stated, "I have no talents other than to dress; my genius is in the wearing of clothes".

Ultimately, Brummell's extravagance in life, rather than purely in dress, brought about his downfall. He fled to France in 1816 to avoid gambling debts, another mark of a gentleman's lifestyle. His legacy, however, lives on. Could the flash City Boy power tie have existed without Brummell's focus on his own neckwear?

Indeed, would our contemporary masculine ideal, focused as it is on sartorial silence, the quiet perfection of the bespoke tailored suit, be quite so finely-honed? Brummell didn't invent it. But he ironed out the creases early on. As he himself asserted, his genius of wearing clothes, well, is how he is remembered. A statue of him stands on Jermyn Street, in the heart of London's menswear district. No better resting place, really.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies