How Le Creuset became top of the pots: Inside the factory creating modern heirlooms for daily life

There are cooking utensils, and then there’s Le Creuset. Thea Lenarduzzi travels to Picardy to find out how this most venerable of brands entered not just our kitchens but our hearts

Frédéric Sallé pushes the last of his boeuf bourguignon to one side and claps his hands. A slight man in his mid-forties, wearing mustard trousers and workman's boots, M Sallé is enjoying a meal in the airy annex of a factory in windswept north-east France. He is in a mood to celebrate.

It was here in the town of Fresnoy-le-Grand (population 3,000) that the manufacturer of everyone's favourite pots and pans was first established in 1925 – a brand so synonymous with France that one of its flame-orange casserole dishes might as well adorn the national coat of arms. And as Le Creuset – literally, “the crucible” – turns 90, M Sallé, the factory manager, is one of those charged with helping to ensure that the company's future is as successful as its past.

Le Creuset pots rank alongside Farrow & Ball paint, Anglepoise lamps, and Mogensen leather sofas as arbiters of middle-class style the world over; so much so that the author Christopher Matthew got a book out of the idea – The Man who Dropped the Le Creuset on his Toe, and Other Bourgeois Mishaps.

A peer survey confirms this, with reasons given for using a Le Creuset including: aesthetic appeal; versatility; reliability; sentimental value; that it is virtually indestructible but comes with a lifetime guarantee, just in case; and its reassuring weight – roughly the same as the large, organic, free-range chicken (ethically sourced by a local butcher) that users are wont to place inside it. Above all, Le Creuset provides a stable backdrop to the shifting patterns of culinary life as expressed in everything from a rushed late-night pasta sauce to an eight-hour braised shoulder of lamb with apricots and ginger. It specialises in the kind of food that is difficult to get wrong – the one-pot wonders that comfort us from childhood through to old age.

But it takes energy to create such a sense of ease. “Every day the plant uses two times the electrical supply of the whole town,” M Sallé says, as he taps his spoon across the crust of a crème brûlée – another classic from the Le Creuset repertoire. Does he live in fear of power cuts? “It would be a disaster, yes… but we have measures in place,” he says enigmatically. He has overseen 40 tours of the facility in almost as many weeks, but it's clear that he's raring to go round again.

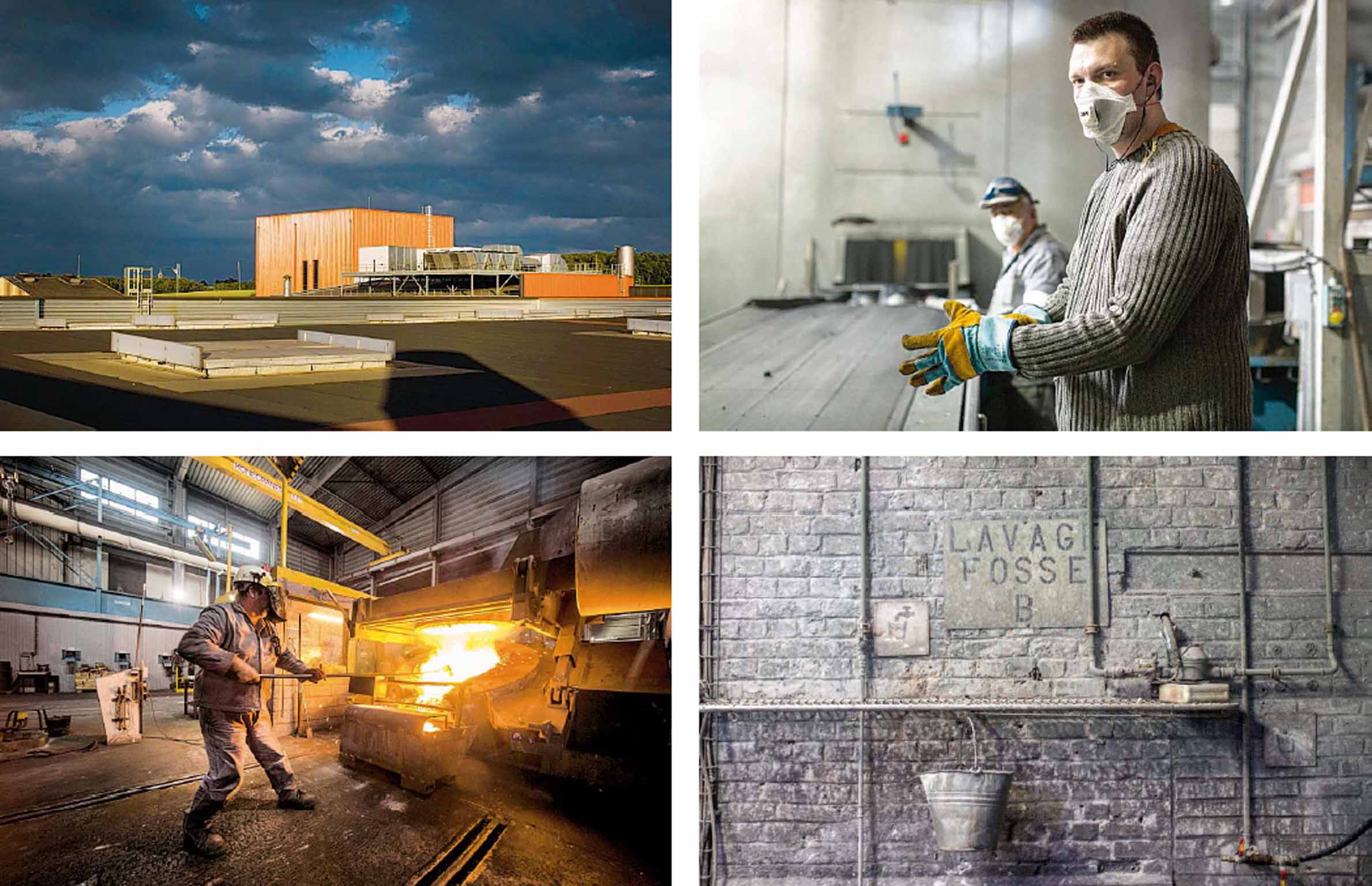

The Le Creuset complex nestles among brown-and-green-striped fields farmed for sugar beet and wheat. It also sits at a historic crossroads for the transportation of coke, iron and sand – the raw materials that go into every cast-iron pot and pan still forged on the site. Not much has changed over the years in the area surrounding the factory, but a great deal is changing within its walls.

A £100m redevelopment – allegedly paid for in cash by Paul Van Zuydam, a South African businessman who bought the company in 1987 – has allowed the plant to double its capacity: 20,000 pieces are now turned out every day. At the expansion's heart is a bright orange tower: the new foundry, a beacon in an otherwise bleak landscape of high unemployment and First World War sites.

Le Creuset itself must have been something of a beacon when it first appeared in French shops and department stores, the brainchild of two Belgian industrialists, Armand Desaegher and Octave Aubecq. Little is known about the men except that they met at the Brussels Fair only a year before opening the factory and offering employment in an area devastated, economically and emotionally, by war.

The partners' aim was simple, and it still applies today: to position the brand at the forefront of culinary technology and design, combining specialisms in casting, enamelling, and consumer psychology in a range of covetable pots and pans. At > a time of empty seats around the kitchen table – an estimated 700,000 Frenchwomen were widowed by the First World War – the arrival of Le Creuset must have been particularly cheering, as though the stoicism of the nation had been captured and coated in 1920s verve.

As food rationing slackened, Le Creuset rode a wave of culinary modernisation, set in motion by Georges August Escoffier, a blacksmith's son who reignited national pride in the kitchen. (The British may prefer to remember him as the Savoy's first head chef, who refused to learn English lest it contaminate his dishes.)

Meticulously engineered pans found eager customers then as they do now: thin cast iron – “still the thinnest and lightest,” says M Sallé – allows for even heat distribution and superior heat retention; long-lasting enamel resists staining and the absorption of flavours; and the pale interior makes it easy to monitor food as it cooks.

The brand remains steeped in foodie philosophy, which, says Ingrid Lung – now senior brand manager at Le Creuset's London office, having started her career at the company 16 years ago (“My first job… my mother was thrilled!”) – accounts for its resilience. Like the best French fashion houses, the company doesn't release sales figures, though Van Zuydam regularly reports double-digit growth.

A glance at the anniversary microsite, lecreuset90.com, which encourages you to “share your stories”, confirms Mme Lung's theory. There are recipes for okonomiyaki, Durban fish curry, and dark chocolate and almond soufflé. A YouTube channel dedicated to Le Creuset offers “Harvest to Heat”, a series riffing on the farm-to-table ethos, as well as a popular strand in which chefs take on the “five-ingredient challenge”. Then there are the thousands of fan videos, from the pedestrian (“How to fry an egg using a Le Creuset skillet”), to the topical (“The perfect holiday goose”). A spin-off category demonstrates how to care for your treasured pot.

The care factor is, in fact, over-emphasised, M Sallé and Mme Lung agree. As well as being dishwasher-proof, unlike many cast-iron products, Le Creusets require no seasoning; enamel is already the most even and hygienic sealant around. They are also designed to withstand even the most enthusiastic scraping.

The brand prides itself on creating modern heirlooms which, far from sitting in the attic, participate in daily life before being handed down. The internet is woven through with stories of “the pan my grandmother gave me”, “the pot I was given when I got married in 1973, and didn't know how to cook…” And Le Creusets are the focus of these stories like no other brand, cited with pride and a sense of communion.

But the question arises: how can the company maintain healthy sales if the goods are outlasting their owners? “To stay relevant is the hardest thing,” says Mme Lung – people need to want to update their collection. This year saw the first redesign of the original 1925 model in 50 years. “The handles are easier to grip, and the ridges on the lid are more prominent, too, purely for the look,” Mme Lung explains. The new lid handle is heat-resistant and more ergonomic – though it still provides a steady plinth, when you upturn the lid, on which to rest a heavy roasted bird while you deglaze the pot for gravy.

The brand has always embraced trends, developing grills (in the 1950s, when grilling was first linked to healthy eating), fondue sets, woks and tagines. Recent years have seen the advent of paella and pizza pans, tapas and balti dishes. There have been collaborations with chefs, including, in the UK, Ollie Dabbous and the Chiappa sisters – “We don't pay them,” Mme Lung is quick to point out. “We know they would use us anyway so we just > ask them to share the experience.” A “Gastro-Pub” range of oven-to-table cookware, devised in tandem with the chef Tom Aikens, has just launched.

Expansion into accessories – everything from spatulas to glass decanters – is key. As with most foodies, branching into wine has long been part of the equation, says Mme Lung – ever since Van Zuydam bought Hallen International Inc from its founder, Herbert Allen, who had invented the first “screw-pull” corkscrew in 1979. Allen, so the story goes, was having dinner at home in Texas when his wife challenged him to come up with an uncorking device that required no tugging whatsoever. That he was nearly 80 and still at the cutting edge of design must have struck a chord with Le Creuset. Van Zuydam bought the patented technology a couple of years before Allen's death, in 1990, ensuring its legacy. The original now resides at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, while its offspring – including the updated lever model, now made by Le Creuset – are Christmas-list staples.

But it all began with the cocotte, coated by Desaegher and Aubecq in Volcanic-Flame orange, inspired by the molten iron used in production. The name translates as “small oven”, and this year, in honour of Le Creuset's foundation, 1,925 replicas went on sale for £299 each, complete with a certificate of authenticity.

After the cocotte came a steady stream of models, each blending forward- thinking with heritage. By the mid-1950s, Le Creuset was exporting across Europe, but the most significant change was that 50 per cent of production was being shipped straight to the US. And Julia Child – the rollicking Cordon Bleu-trained Californian who, in books and TV series, encouraged Americans to embrace a French approach to food (“Get good and loaded and whack the hell out of a chicken”) – was largely to thank. So established is the Le Creuset-Child connection, Mme Lung says, that, when the film Julie & Julia was released in 2009, starring Meryl Streep as Child herself, “sales whooshed”.

The UK also came on board, an awareness of Le Creuset all part of the culinary awakening brought about by the food writer and champion of French cooking Elizabeth David. While rationing dragged on into the mid-1950s, David fired people's imaginations with books such as French Country Cooking. Selfridges took the first orders of Le Creuset in 1961 and, a few years later, David herself opened a shop in Pimlico specialising in imported kitchen equipment; her pamphlet “Cooking with Le Creuset” became a domestic fixture. Perhaps by way of recognition, the brand introduced a signature shade of blue, inspired by the Gauloises that David loved to smoke.

The company's logo is a representation of the crucible – the creuset – in which all its cast-iron pots are conceived. Here, M Sallé explains, unfazed by the spitting lava behind him, 15 per cent pure pig iron is blended with 35 per cent recycled steel and 50 per cent iron, at a temperature of 1,500C for 40 minutes. If the consistency isn't perfect, subsequent enamelling will fail. The precision couldn't be further from Child's slapdashery.

Next, impurities are removed with a long wooden spatula. Though the factory's work is increasingly automated, this stage requires a “human touch”, M Sallé says. The liquid is transferred to a casting machine, and poured into sand moulds, formed by “male” and “female” parts that fit together as you would imagine, leaving a 3mm space. The moulds are filled at a rate of 500 an hour, with each being used only once – “so each piece is unique”, Mme Lung adds. This requires an endless supply of sand (98 per cent of which is recycled), which is stored in towering blue vats intersected by yellow pipes and steel funnels. Richard Rogers himself might have designed it.

After cooling, pieces are blasted with grit and then fettled, smoothing the edges. Though much is still done by hand, “robots” were introduced eight years ago. “It's tough work,” says M Sallé, “and we're in a state of permanent innovation.”

Innovation is what Le Creuset is founded on, since Desaegher and Aubecq first coated cast iron with enamel. “Scientists say it's impossible,” M Sallé explains. “Metal expands when it's heated, but enamel can't – it's glass – at 200C it shatters. It's extremely difficult to perfect this technology. And that's why we have no competitors.”

His confidence is itself rooted in solid, sometimes pleasingly rudimentary, science. “We test ours against all others” – by which he means “imitators” such as Denby, Lakeland and even Tesco, who would lure buyers with cheaper alternatives. Tests include being whacked with a hammer – “You see? It marks. But here” – whack – “no mark” – and being held up to flames, steam, boiling oil.

Each piece passes through six inspections, carried out by specialists capable of spotting the most inconspicuous of inconsistencies. This too contributes to the high cost of the finished product, explains Mme Lung, the smallest round casserole costing £75. “Le Creuset outlet” and “Le Creuset sale” are among the most common related internet search terms – an indication not only of the comparatively high prices but also of our determination to snap up our own nonetheless.

Colour remains one of the most effective ways of keeping people interested, says Mme Lung, but each one can take up to six months to perfect. “Colour is one of our most important features – we offer 100, where others can do only 10.” These range from the classic – Cerise, Volcanic, Cotton – to the quirky – Chiffon Pink, and Elysée Yellow. (The latter was reintroduced this year for a limited run and one can only wonder what took them so long: Marilyn Monroe's Elysée Yellow 12-piece set sold for $25,300 in 1999.)

Attempts to reach beyond the brand loyalists – primarily women aged 35 –55 – and appeal to men as well as young urbanites, have included ranges in Satin Black and Ink, Cassis and Teal. It's all part of a strategy devised by Van Zuydam to make Le Creuset truly global. This year, he announced a five-year plan to open 100 new stores a year, right across the world. This kind of presence, as well as the continued development of stoneware and stainless steel ranges, is sustained by a similarly global network of factories – in China (accessories), Thailand (kettles and ceramics), Portugal (stainless steel), and the US (enamel cleaner). For cast iron, though, “it's very important to stay in France”, says M Sallé – for the emotion and psychology of the brand, if not for the accountants' peace of mind.

For M Sallé, it all comes back to the crucible: if the recipe isn't right, if your equipment lets you down, if your heart isn't in it, all is lost. At the end of it all, you need to have the confidence to be able to use and abuse your cookware. “Japanese visitors are so cautious and respectful. So I like to pick up the lids and throw them about.” He smiles. He's made his point. This factory specialises in beauty that lasts, and can hold its own. Even in a power cut.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments