The science of sugar and spice

Coffee and beef, strawberries and basil – understanding the exquisite complexity of flavour pairings can transform the way we cook, discovers Clint Witchalls

Some people can make a tasty meal from random ingredients without recourse to a recipe book. Niki Segnit was not one of those people. She wondered what it was that caused her to lack confidence in the kitchen – a confidence that her mother had in abundance. Why did she have to slavishly follow recipes? How do you go from being good at recreating meals from recipes to creating something original and delicious of your own? There was a missing link.

In 2004, having lost her job in advertising, Niki found herself with lots of time to ponder this question. She decided to re-launch herself as a food writer and "being a bit of a swot" immediately began researching the secret to self-assured cooking.

"There was a lot in the ether at the time," Niki told me, when I caught up with her in Battersea. "There was all the Heston Blumenthal stuff – the bacon and eggs ice-cream – and Masterchef had just started again and they were always talking about flavour combinations. I decided, what I was lacking was an understanding of how to combine flavours, so I decided to get a book on the topic."

Only there wasn't one. It hadn't been written, so Niki decided to write it herself. In 2007, Niki hit upon the idea of compiling a thesaurus of flavours. When a trawl on the shopping website Amazon convinced her that no such thesaurus already existed, she was so excited, she almost hyperventilated.

"It was an enormous project and took me to all sorts of different places," says Niki. "It has completely changed my cooking and I'm still not bored with it, after two and a half years."

Niki originally hoped to come up with something resembling a Grand Unifying Flavour Theory "that would reconcile the science with the poetry and my mother's thoughts on jam", but was humbled by the enormity of the task. She settled instead for "a patchwork of facts, connections, impressions and recollections, designed less to tell you exactly what to do than to provide the spark for your own recipe or adaptation."

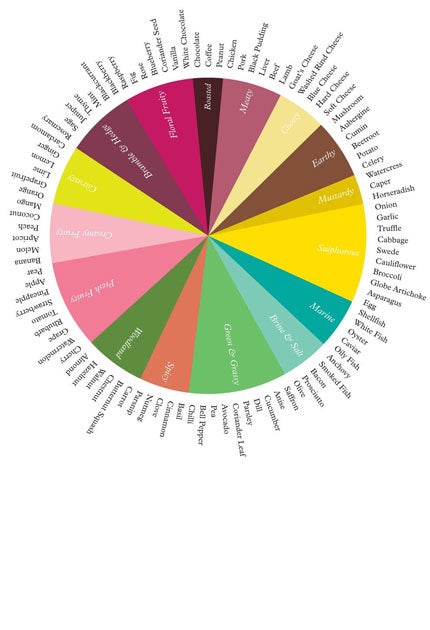

The Flavour Thesaurus takes 99 foods and pairs them against each other, from the classic: lamb and mint, to the exotic: pineapple and anchovy. Pairing 99 flavours equates to 4,851 unique flavour combinations. Sensibly, The Flavour Thesaurus pares this down to 980 combinations. Enough to keep even the most inquisitive gastronome busy for a while. If Niki had opted for flavour trios, she would have had an unwieldy 156,849 unique combinations to contend with.

The thesaurus groups flavours into categories such as: spicy, earthy, sulphurous, and so on. So, truffle and broccoli are sulphurous while cumin and mushroom are earthy.

Writing the book involved a huge amount of research. Aside from interviewing chefs and food scientists, Niki pored over hundreds of recipes and menus to extract the most commonly recurring flavour pairs. Nevertheless, some of the pairings are more niche than others.

Flavour is a complex topic and agreement on which food pairings work and which don't is somewhat arbitrary. Indeed, there were some flavour combinations that even Niki didn't get. "I think the chocolate and beetroot cake which has just done the rounds is terrible – unspeakable!" says Niki. "It tastes like a cake that's been dropped in the flower bed." Beef and coffee was also not one of Niki's favourites (see box).

So, what exactly is flavour? One aspect of flavour is taste. Our tongues can discern five tastes: salty, sweet, sour, bitter and umami (that there are specific points on the tongue to register each of these is a myth). "If you have a cold, you can still taste things," says Niki. "You can still taste that your Lemsip has that bitter taste and sourness. What you can't taste is the lemon flavour."

Flavour combines taste and smell. Flavours reach our olfactory bulb – where we experience smell – through our noses and through the backs of our throats. But there is a third dimension of flavour, called the "trigeminal senses" which allow us to perceive mustard and chilli as being hot, menthol and mint as cool, and tannins as puckerish.

Were there any flavour duets that surprised Niki, in a positive sense? "Yes. Bell peppers and eggs. It's an Italian American obsession in some places," says Niki. "I cooked green peppers until they were just about to collapse and cooked some eggs so that they were just scrambled and put them into this soft roll. It was one of those two-plus-two-equals-five combinations. Oh my god, just so incredible. Beautiful."

Another of Niki's favourites is a strawberry and cinnamon. As a sweet snack, she recommends making a strawberry jam and cinnamon toastie (see box). "It's not very sophisticated but it'll give you a GI [glycaemic index] high that will last for about five minutes before you get the most terrible crash," she says. "But boy it's a fairground ride."

Niki has a way of describing food that has me salivating. I'm grateful when it's finally time to sample the food Niki has prepared. "Here's something I bet you haven't tried before," says Niki, handing me a slice of tomato and a basil leaf. Basil and tomato is such a classic, yet when Niki asks me why I think the combination works, I'm stumped. How do I explain the enjoyment of this simple juxtaposition of flavours?

"OK. Try it with strawberry." Now, that's something I haven't tried and, to be honest, the idea seems wrong, yet it tastes right. Again, I have no idea why. It just does.

Next we try dried apricots stuffed with goat's cheese. It's kind of meaty and chalky at the same time. For Niki, it's redolent of lamb, but I'm not sure. Flavour can also be a lot to do with memory. Maybe Niki's tasted more apricot and lamb tagines than I have.

The Wensleydale and fruit cake combo – a traditional northern dish dessert, I'm told – is on a similar theme of dried fruit combined with a hard, salty cheese. Niki says cheese and apple pie was once a common grouping. In fact, in one US state it used to be against the law to serve apple pie without cheese.

"Try some of this," says Niki, handing me a plate of what looks like baguette smeared with Nutella and sprinkled with pine-nuts. I bite into it. The spread tastes sweet, but in a strange, earthy way.

"What's in this?"

"Pigs blood," Niki says, cheerfully. "It's an Italian blood pudding called sanguinaccio. I got it from Bocca di Lupo. I would have made it myself, but I my kitchen is too small for slaughtering a pig." Horrible as it sounds, blood and chocolate make a beautiful alliance.

The next pair is less bloody but more pungent: truffles and stilton. I try a slice of stilton dribbled with truffle infused honey. The truffle honey has a strong solvent hit to it and I'm immediately taken back to my father's dry cleaning business in Cape Town. I'm about 10 years old, leaning against a barrel of carbon tetrachloride, enjoying my first paid job.

Flavours can be a powerful shortcut to deeply buried memories. It took a mere nibble of a madeleine biscuit to kick-start Proust's seven-volume semi-autobiographical novel: In Search of Lost Time.

"I have a terrible memory and I never take any photographs," says Niki. "But I can really dazzle my husband with my memory if he can start me off on what we ate. I think it's incredible how the brain has a way of accessing information through food. Somewhere in your head, your brain knows the difference between your mum's cottage pie and a pub cottage pie and a ready-meal one."

We finish the "crazy aunt's cocktail party" – as Niki called it – with some homemade orange and coffee liqueur and almond and anise biscotti. Nothing outré, just elegant flavour combos.

Enjoying the heady rush of the liqueur, I wonder who the The Flavour Thesaurus is written for. "I wrote it for myself," Niki says. "I'm a bit too conservative when it comes to cooking so writing it made me more palate conscious; it made me more aware of what something tastes like. As a recipe slave, I was disengaged from what I was doing – just going through the motions, doing what I'm told. I'm good at that, but not necessarily being immersed in the sensual side of cooking."

Being a recipe slave myself, I quite like the idea of being a bit experimental. But I wonder if I have the time for it. And won't a lot go to waste? "Not much goes in the bin," Niki reassures me. "That's what I learned. Some things you think: I won't make that again, but you don't ruin much by being experimental."

The Flavour Thesaurus: Pairings, recipes and ideas for the creative cook by Niki Segnit (Bloomsbury, £18.99. To order this book at the special price of £17.09, including p&p, go to Independentbooksdirect.co.uk or call 0870 0798897

Perfect partners?

Coffee & Beef

Caffeinated red meat. Something to serve your most militantly health-conscious friends. Coffee is used in the American south as a marinade or rub for meat. It's also been spotted in fancier restaurants, perhaps because there's a well-reported flavour overlap between roasted coffee and cooked beef. But my experience suggests it's a shotgun wedding. I tried a coffee marinade on a steak and found it gave the meat an overpoweringly gamey flavour. Best to keep these at least one course apart at dinner.

Black Pudding & Chocolate

A mixture of chocolate and cream is combined with blood to make the Italian black pudding, sanguinaccio. If that doesn't sound rich enough to begin with, it's often embellished with sugar, candied fruit, cinnamon or vanilla. Sanguinaccio is sometimes made into a sausage form, like other black puddings, but is also eaten (or drunk) while still in its creamier liquid state.

Strawberry & Cinnamon

Strawberries have a hint of candyfloss about them. Cinnamon loves sugar and fruit. Warmed together, the pair gives off a seductively seedy fug of the fairground. For an irresistible sweet snack, dig out the sandwich toaster, butter 2 slices of white bread, spread one slice (on its unbuttered side) generously with strawberry jam, and the other with more butter and a good shake of ground cinnamon. Sandwich together, with the just-butter sides facing out, and press in the toaster till the bread is crisp, golden and, essentially having been fried rather than toasted, more like a doughnut than plain old jam on toast.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks