Could full body transplants really be possible within two years?

Italian neurosurgeon Sergio Canavero believes so - and it's not quite as implausible as it sounds, says Steve Connor

In ancient Indian folklore Sita is in love with two men, her husband Shridaman and his hunky friend Nanda. Shridaman is the intellectual with the body of a wimp, while the muscular Nanda has little to offer in the upstairs department.With the help of divine intervention, the two men magically switch heads, confusing Sita no end because she can't decide which version represents her real husband. Heads seem so critical to our identity and personality, and yet it's the body that makes us what we are.

We are used to the notion of transplanting organs, and even faces, but head transplants? Indeed, the terminology itself is confusing, as such an operation really should be described as a "body transplant", given that it is the dead person who donates the body and the living recipient who keeps his or her head.

Sergio Canavero, the Italian neurosurgeon who is proposing to carry out the first human head (or body) transplant, is well aware of the ethical and philosophical issues posed by such an operation.

"The 'chimera' would carry the mind of the recipient but, should he or she reproduce, the offspring would carry the genetic inheritance of the donor," Dr Canavero wrote in 2013, when he first proposed that it would be two years before we see the first human head transplant.

Two years later, Dr Canavero has made the news again by proposing that it will take only two further years of research until we are transplanting the head from a patient with a broken body on to the neatly severed neck of a donor's freshly-dead cadaver.

"It will always be two years," he tells me, by telephone from Italy, where he heads the Turin Advanced Neuromodulation Group. "That's how long I need to organise the crew of surgeons."

Few other neurosurgeons go along with Dr Canavero's optimistic timeline, and a substantial number believe that such on operation could never be contemplated. Connecting blood vessels and tissues are not so much the problem, it's the fusing of one spinal cord to another so that the brain can communicate with the rest of the body. Dr Canavero, however, is adamant.

"We have the technology to do this right now in humans… we just need the ethical approval and the funding to do it," he says. He believes it could be done by cooling the bodies of both donor and recipient to the point of hypothermia. Once this has happened, the two spinal cords could be severed neatly with ultra-sharp blades and bathed in polyethylene glycol to help them anneal correctly, so that the head can communicate to its new body, and vice versa.

"This is of course totally different from what happens in clinical spinal cord injury, where gross damage and scarring hinder regeneration. This 'clean cut' is the key to spinal cord fusion," Dr Canavero says.

In 1970, American neurosurgeon Robert White famously carried out a similar head transplant between macaque monkeys. The monkey lived for eight days, although it was effectively paralysed from the neck down as no attempt was made to connect the two spinal cords.

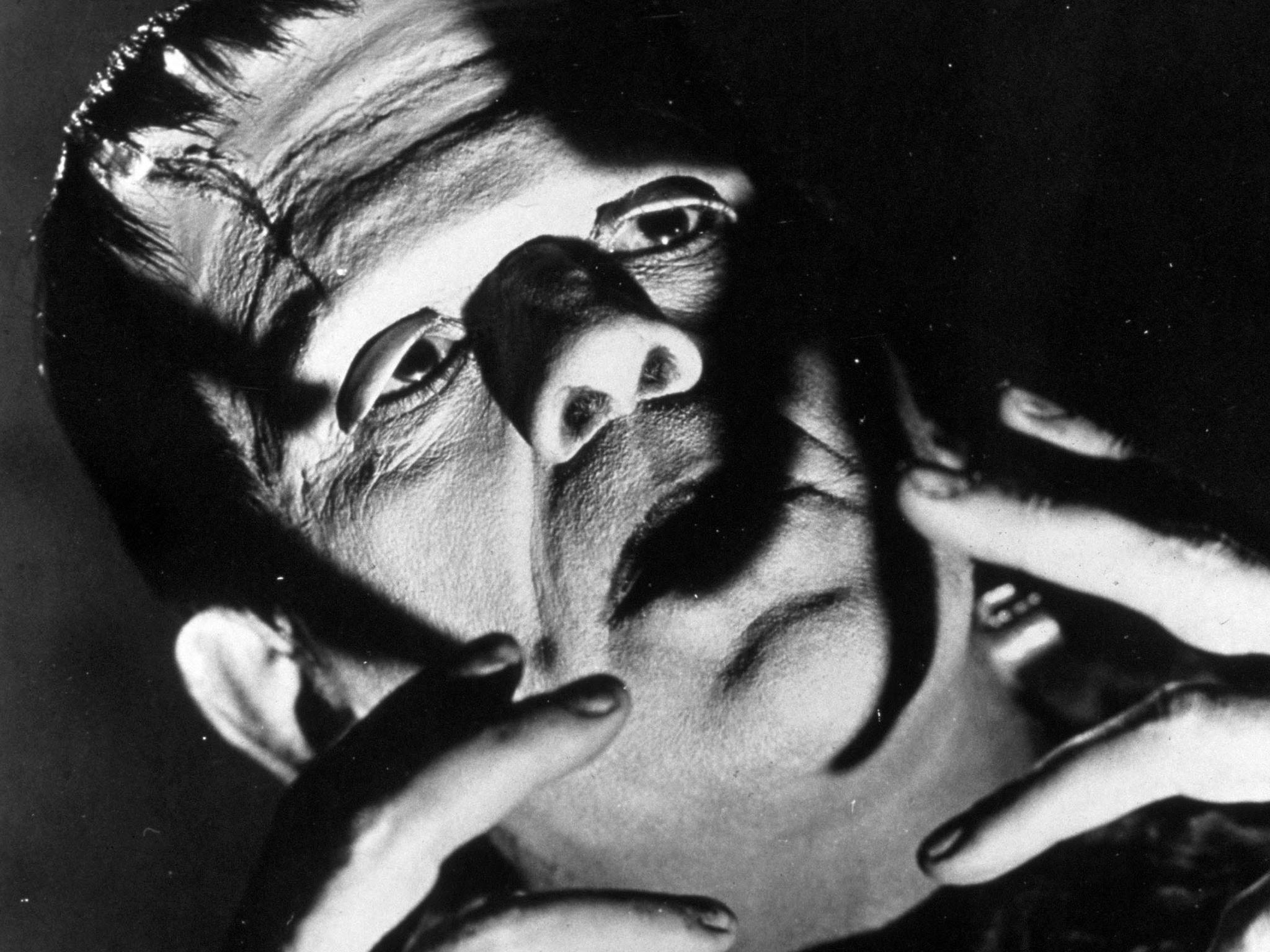

Nevertheless, Dr White predicted in 1999: "What has always been the stuff of science fiction – the Frankenstein legend, in which an entire human being is constructed by sewing various body parts together – will become a clinical reality early in the 21st century."

Dr White believed that such a radical procedure would be suitable for terminal cancer patients. Dr Canavero, however, suggests that it would be better suited to younger people suffering from conditions that leave the brain and mind intact but cause devastating damage to the body, such as progressive muscular dystrophies.

"They are a source of huge suffering, with no cure in hand," he says. "I really believe it will be done. It will be the new space race of the 21st century with America and China competing to be first."

But Dr Canavero is something of a lone voice. Harry Goldsmith, professor of neurological surgery at the University of California, Davis, was unequivocal: "The possibility of it happening is very unlikely."

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies