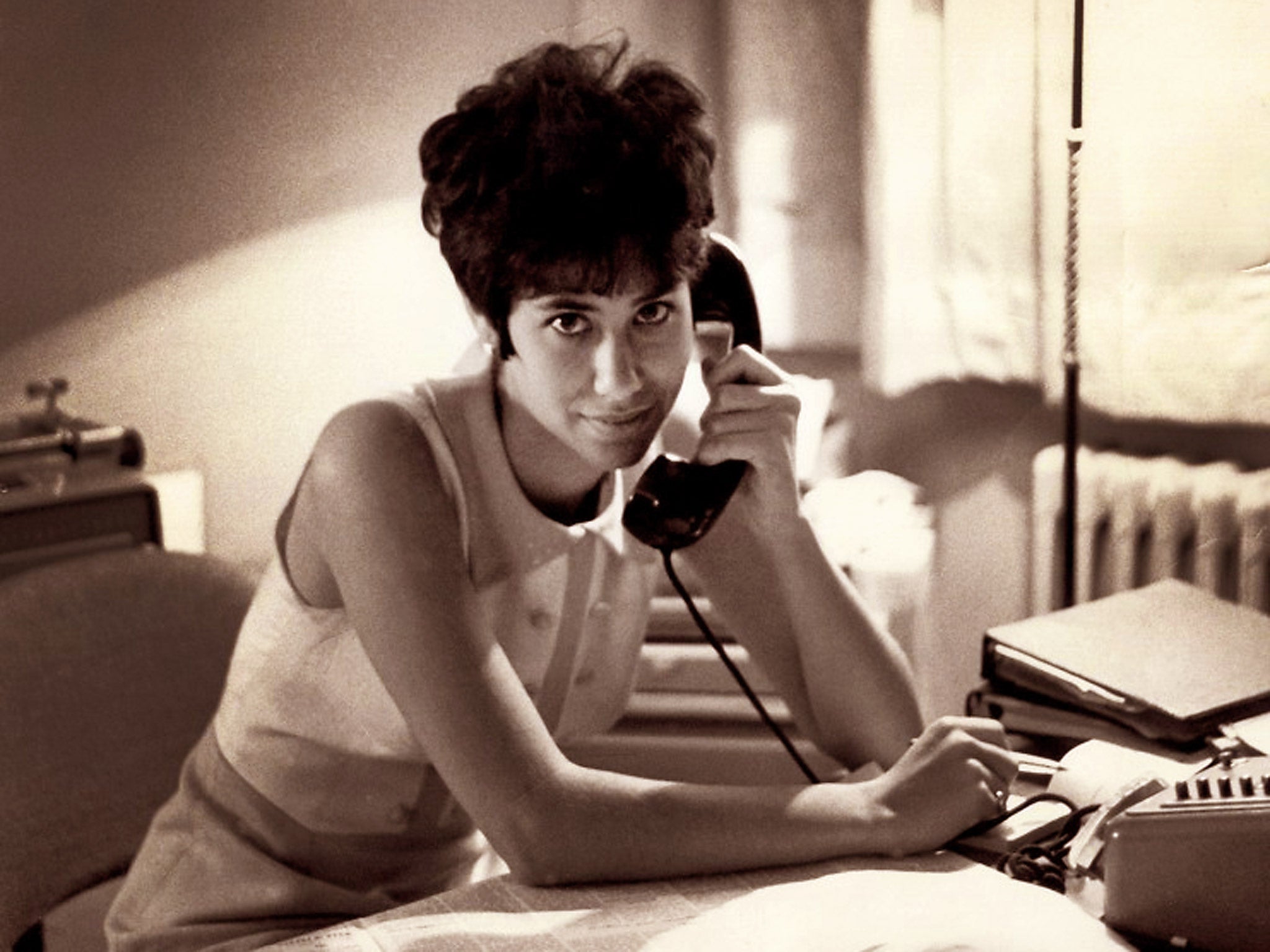

How a fed-up group of ‘Good Girls’ beat the ‘Mad Men’-era sexists

Fed up with hitting the glass ceiling at Newsweek in the 1970s, a group of women sued the magazine, demanding better opportunities for advancement. Now their story has been turned into a new series on Amazon Prime

In the late 1960s, the national researchers at Newsweek magazine were known as “the Dollies”. The Dollies were all women, and when they handed over the results of their work to their male bosses, they were apt to hear about their “perfectly pointed breasts.”

The Dollies were stuck in place, consigned by decades of tradition to a secondary role, with little hope of promotion. The boys did the writing and got the glory. The girls did the journalistic spadework and fetched the coffee. It felt like the natural order to many of the Dollies. They’d grown up in a world that accepted this kind of system, after the fashion of Mad Men, and even though lots of them had gone to elite schools and were crackling smart, they were constrained by the limits of what they could imagine for themselves. They were “polite, perfectionist, good girls who never showed our drive around men,” Lynn Povich, a former high-ranking Newsweek editor, writes in her book, The Good Girls Revolt, the inspiration for a fictionalised television series of the same name from Amazon Studios that began streaming on Friday.

Povich was one of the leaders of a group of Newsweek women who sued the magazine in 1970 demanding better opportunities for advancement in a case that eventually set in motion seismic changes at the venerable publication and had a ripple effect across the media landscape. They assembled 46 cohorts, recruiting new plaintiffs one by one in hushed, nervous conversations in the Newsweek ladies’ toilets or behind closed office doors. Their attorney was a young civil rights lawyer with a spectacular afro and a fearsome demeanour named Eleanor Holmes Norton – now the District of Columbia’s longtime congressional representative.

The book that inspired the series was published in 2012, but Povich says she resisted allowing it to be adapted for the screen. She warmed to the idea after Lynda Obst, the executive producer of Sleepless in Seattle, took an interest. In an era when Hollywood is often criticised for the paltry number of women in leadership roles, Povich likes the idea that women, including show creator Dana Calvo, a co-executive producer of Narcos, were among those heading the production. But Povich says she insisted that the series not be tethered to the nonfiction model. “I didn’t know if they were going to get it right – most real stories that get translated don’t come out the way you want them to,” Povich says one afternoon over lunch on New York’s Upper West Side. Another thing gave her pause about naming names in a nonfiction rendering: “There was going to be sex.”

Lots of sex. Only a few moments pass in the pilot before a young researcher slips into the Newsweek infirmary for a steamy quickie with one of the big-shot correspondents. In the real-life Newsweek offices, a married male editor regularly used the infirmary for trysts, Povich says. Some elements of the series, as is often the case, bother actual participants. Mary Pleshette Willis, a novelist and former Newsweek researcher, was irked that writer Nora Ephron, who worked briefly at Newsweek, plays such a central role in the pilot. Ephron is deftly portrayed by Grace Gummer, the daughter of Meryl Streep, who played a character inspired by Ephron in the film Heartburn.

“She had absolutely nothing to do with it. She left before we organised... it was to me a sort of inaccuracy that irritated me,” says Willis, who otherwise enjoyed the pilot. Lucy Howard, a plaintiff who went on to have a long reporting and writing career at Newsweek, thought the pilot was fun but chafed at the portrayal of the male editors and writers, whom she remembers as brilliant journalists. “They came through like fools,” Howard says. Calvo says she wanted to make a “fun, sexy, adrenaline-filled” series and that the production was designed to “serve the story – not the history. ”

Povich is tall and poised, with striking blue eyes and a long face that is all sharp angles. She has inhabited a rarefied world of media and cultural elites but enjoys a kind of comfortable, unpretentious anonymity. “I’m not Nora Ephron,” she says. At 73, Povich, who became the first female senior editor at Newsweek and later served as editor in chief of Working Woman magazine and helped launch MSNBC.com, no longer occupies high-energy newsrooms. She takes tap-dancing lessons now, she says with a smile and a tiny shrug. She grew up in Washington, the daughter of famed Washington Post sports columnist Shirley Povich. His friendship with Katharine Graham – the publisher of The Washington Post, which also owned Newsweek – helped her land a low-level job in the magazine’s Paris bureau. She later moved to New York to work as a researcher. The back-of-the-book offices were “action central,” where editors and writers would go to “take a nap for an hour or two, albeit with a female staffer,” Povich writes. The former Newsweek writer Jane Bryant Quinn told her that “randy writers and editors would cruise the newcomers letting them know that their so-called careers would be helped if they joined the guys for drinks.”

Povich, who was married at the time, got caught up in the freewheeling vibe and had an affair with a Newsweek colleague. When she told her husband – filmmaker Jeffrey Young, son of a prominent restaurateur – he confessed that he’d been having an affair, too. They tried to work it out but would later divorce. Povich had a few dates with actor Warren Beatty before marrying her current husband, then-Newsweek editor Steve Shepard. The good girls’ revolt began with a researcher named Judy Gingold, an Oxford-educated scholar who’d been attending feminist consciousness-raising meetings. When Gingold called the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, the woman who answered the phone scoffed at her plan to negotiate with the magazine’s higher-ups in hopes of changing the pattern of relegating women to researcher roles. “Don’t be a naive little girl!” the EEOC official told her. Gingold, following the EEOC official’s advice, began secretly recruiting allies.

Gingold and the others opted not to include several women who were dating top editors or writers because they were worried about their secret plans being disclosed. The good girls couldn’t afford a high-powered law firm. But Eleanor Holmes Norton, then an American Civil Liberties Union attorney, was intrigued by their cause, in part because it presented an opportunity to expand the public notion of civil rights. “Feminism was only beginning to be understood as a civil rights issue,” Norton recalls in an interview. The Newsweek women would meet at Norton’s apartment on West 104th Street in New York, where the new attorney, who was pregnant, advised them while slicing raw onions, her pregnancy craving. “You gotta take off your white gloves, ladies,” Norton told them. “You goddamn middle-class women – you think you can just go to Daddy and ask for what you want?”

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

On 26 March, 1970 – in sync with Newsweek’s “Women in Revolt” cover hitting newsstands – they filed their lawsuit. The New York Daily News headline read: “Newshens sue Newsweek for ‘equal rights.’” The article noted that there were 46 plaintiffs, “most of them young and most of them pretty.” It was an awkward spot for Povich, who considered herself part of a “Washington Post family.”

“She wasn’t very helpful in the beginning,” Povich says of Graham. “Most people wouldn’t know it. They only know her as this great courageous publisher... Over the years, I grew to admire Kay’s courage, especially during Watergate.” In later years, Graham would be frank about being slow to embrace the feminist movement. Norton has said she and Graham would become friends many years later, and she described the publisher as “a true convert” to women’s rights. Within weeks, the plaintiffs agreed to a settlement with the magazine that promised “substantial rather than token changes,” including invites to the editorial lunches and a commitment to identifying women who were candidates to become senior editors. Some women also got tryouts as writers. But few felt they got a real chance to succeed. Pleshette Willis’s boss wouldn’t publish anything she wrote. When Povich wrote her first cover story, a piece on the fashion designer Halston, the editor Osborn Elliott sent her a note: “Congratulations on losing your virginity in such style.”

By late 1972, the women had had enough. Norton had moved on to New York City’s Human Rights Commission, so they found another lawyer, Harriet Rabb, and filed another lawsuit. This time they got Newsweek to make firm commitments. The magazine promised that by the end of 1974, one-third of the magazine’s writers and domestic reporters would be women and that by the end of 1975, one-third of the journalists hired as foreign correspondents or transferred into those posts would be women. As a result of the pressure brought to bear by the lawsuits, they also got to participate in writer training programmes, although some women were still so insecure after years of being second-tier staffers that they would turn in their work for review under pseudonyms.

Lucy Howard became Emily Bronte. But she would leave Bronte behind. Howard went on to have a 39-year career at Newsweek, serving in the Washington bureau and eventually being promoted to senior writer. Might the transformation of a good girl who hid behind the name of a 19th century novelist to “Lucy Howard, senior writer”, have happened without a lawsuit concocted in a ladies’ bathroom? Howard has no doubt about the answer to that question: “No way in the world. ”

‘Good Girls Revolt’ is available to stream on Amazon Prime now

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments