Budget 2015: Everything's coming up roses... no thanks to our political masters

Unpredicted economic events have combined to cut government costs while raising living standards

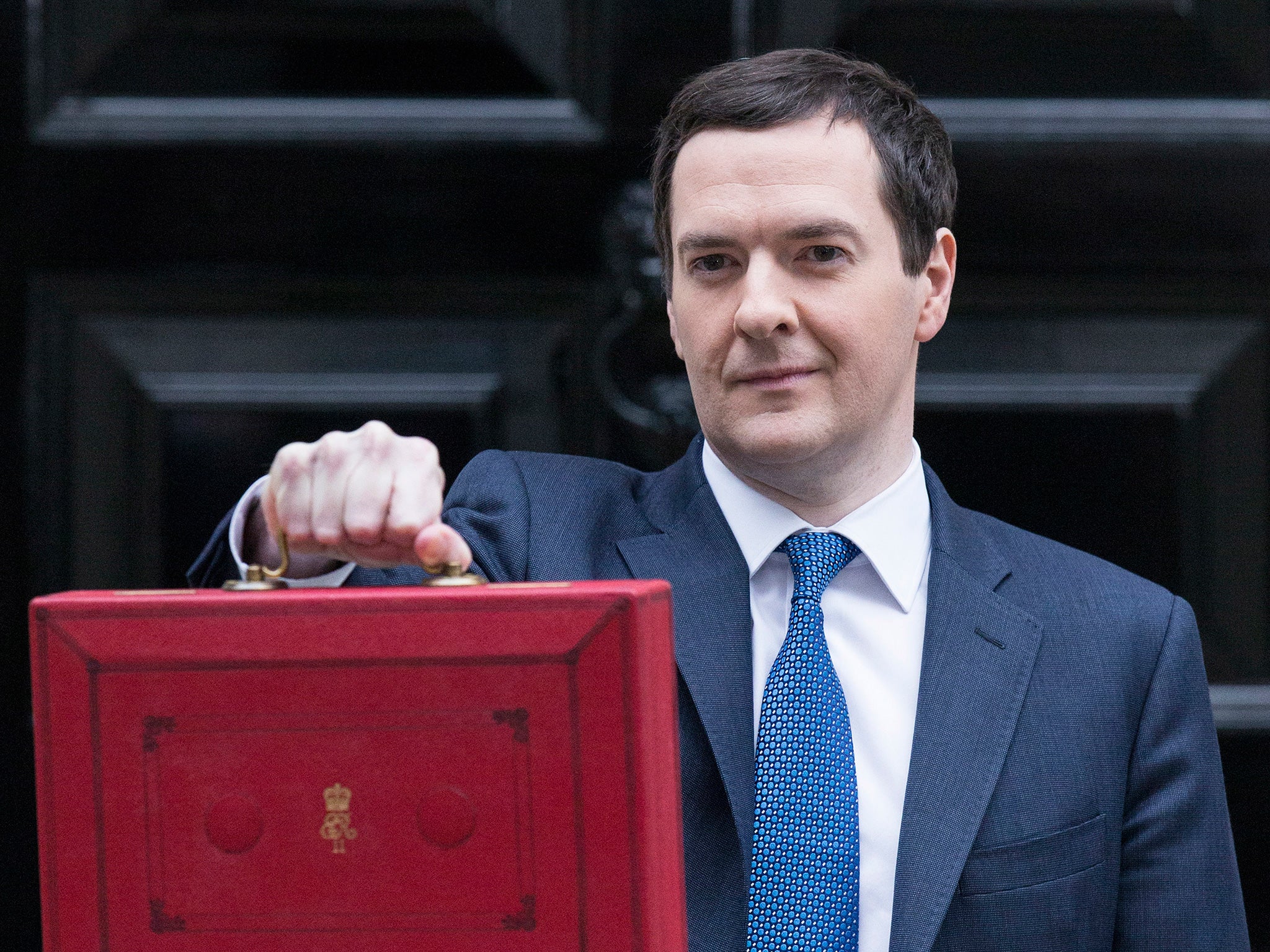

The politics will change but the maths won’t. Fortunately for our political masters – and more importantly ourselves – the maths is getting a little better. We will catch some feeling of how much better on Wednesday, when George Osborne gives the last budget of this parliament. It will be an interim budget, for even if the Tories lead the next government, policies will be trimmed after the election. But the economic backdrop to the budget remains the economic backdrop, and the news there is that in its early years at least, the next government is likely to catch more of a following wind.

There are three broad areas in which the outlook has improved, none of which has anything to do with the Government. One is the fall in the oil price; a second is a slight uplift in European growth; and the third is the fall in borrowing costs.

The fall in the oil price caught just about everyone by surprise. It halved in six months, a change that is at the extreme end of past experience. While we cannot know how long it will remain at present levels, it has already set in train a string of economic benefits, including a boost to living standards throughout the developed world, and in most of the emerging world too.

Though Britain is still an oil producer, it is, with the decline in North Sea output, a net importer. The result is that, coupled with some underlying growth in real wages, we have the fastest increase in living standards for a decade. About time too, you might say. It has also been the main force behind the improvement in our trade deficit, which narrowed in January to the lowest level for 18 months. True, the lower price leads to a shortfall in oil tax revenues, and more will have to be done to ease the tax burden on the industry. But the net loss of tax is quite small in the totality of Government revenue, particularly if lower energy costs lead to faster growth.

Europe is interesting, and not just for the shenanigans over Greece. Even before the European Central Bank (ECB) started its quantitative easing programme (QE), there were signs of a modest uplift in eurozone growth. It was uneven and will remain so. On balance, the ECB’s version of QE will probably disappoint. But some sort of spontaneous recovery was already happening. Car sales in western Europe were up 7.6 per cent in February, after an equally strong January, and once as large a sector as the automotive industry gets going, it pulls other chunks of the economy with it. German growth for 2014 has been revised up to 1.6 per cent, and retail sales are rising at their fastest pace for six years. Since poor demand in the eurozone has been the main drag on UK performance, any uplift is welcome.

The third big change is the cost of borrowing. European sovereign yields are now the lowest they have ever been. Yup, ever. German 10-year bonds hit 0.2 per cent last week. Some of us think that level is an absurd aberration, and will be seen as such in a few years’ time. But the side-effect has been to pull down borrowing costs of all governments, including our own. Ten-year gilts were yielding 1.7 per cent on Friday, a full percentage point lower than a year earlier and while not quite as low as they were three years ago, pretty stunning. Any reduction in the Government’s funding costs makes it easier for it to hit its fiscal deficit targets. Barclays calculates that lower-than-expected fund costs will cut spending by about £1.2bn this year. Thanks to this and other changes, it looks as though the fiscal deficit this year will be a couple of billion lower than the Office for Budget Responsibility expected in December, with further improvements in the years ahead.

What does all this mean for us? Politics being politics, there will be stuff about the Chancellor “giving away” a pre-election bonus – an infuriating phrase, since he is not giving away anything, merely taking a bit less. But the reality is that the next government, thanks to these following winds and assuming reasonable discipline on spending, should be able to correct the deficit over the next three years rather than the next five. That does not get us back to the original plan of the coalition to eliminate the deficit, but it goes some way towards it.

But do we need to have a surplus, or would it be adequate (as Labour proposes) just to start reducing the national debt in relation to GDP? In other words, would it be good enough to have a deficit of, say, 2 per cent of GDP? That should be the key economic question at the election: how prudent should the next government be? My judgement, for what it is worth, is that it would be safer to err on the side of prudence, because there is a strong probability of the next global recession happening during the next parliament. They seem to come at 10-year intervals and 2018 is not that far away.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments