Hamish McRae: How Europe can shore up its rescue of the single currency

Economic Life: In the early days being in the euro enabled countries to borrow more cheaply... now the reverse has happened, even for the AAA-rated

The long agony continues. The outcome of Europe's sovereign debt crisis is no nearer, nor indeed any clearer. But the scale of the problem is, if anything, growing and the damage caused by the weak official response is looming larger, even for non-euro countries such as the UK.

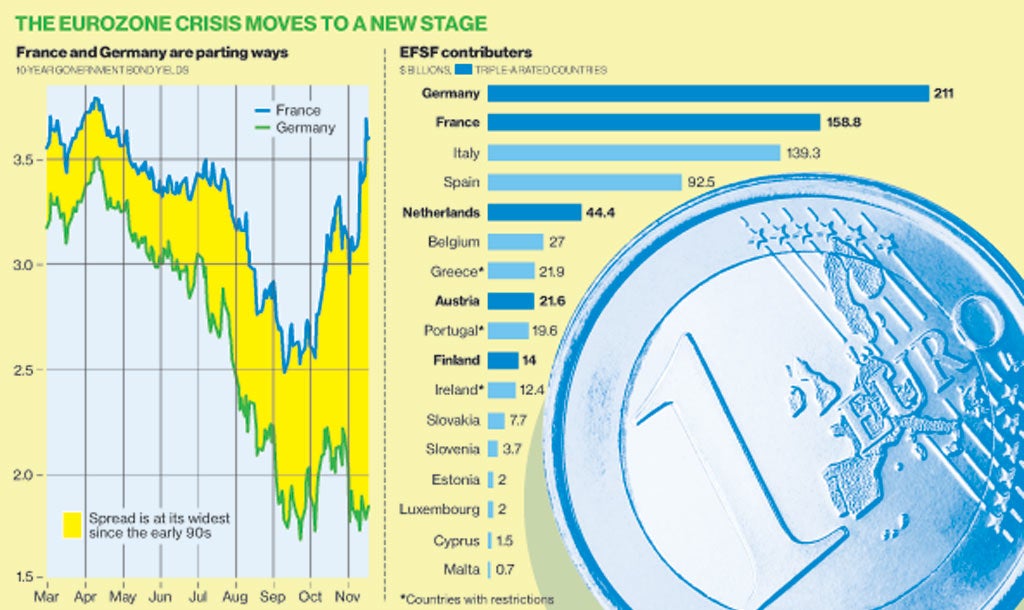

The element that has become clearer this week is that eurozone membership now carries an interest-rate burden for all members bar Germany. There was a bit of a kerfuffle yesterday as Spanish 10-year debt rose towards the 7 per cent crisis level but you can see this most clearly in the case of France. France managed to get away some five-year debt at 2.8 per cent yesterday, which does not sound too bad, but that is half a percentage point higher than it had to pay a month ago. More tellingly, the yield on French 10-year debt is now nearing 4 per cent – more than 2 per cent points higher than the equivalent German debt. (You can see this divergence in the top graph.)

Britain, by contrast, would have to pay around 2.2 per cent on 10-year debt. Yet the overall fiscal positions of Britain and France are broadly comparable. Both have AAA ratings and while France has higher debt levels, Britain has a larger deficit. So you could say that the penalty France is paying for being in the eurozone is about 1.5 per cent, maybe a bit more. What has happened is that in the early days of the euro, being a member enabled countries to borrow more cheaply than they otherwise would. But now the reverse has happened. Being a member carries a cost, and a cost even for countries with a AAA credit rating.

This loss of confidence in any bonds issued by eurozone countries, bar Germany, has weakened the ability of the region to help the weaker countries. I had not quite realised how bad things were until I started looking at the finances of the European Financial Stability Facility. (I am grateful to Louise Cooper at BGC Partners for these alternative interpretations of its initials: Europe's Flawed Survival Fund; Euro's Fund Smells of Failure; Expected to Fail, Sure to Fail; and Every Fumble Speeds Failure.)

Technically the EFSF has a AAA rating, thanks to the similar ratings of its two largest contributors, Germany and France (see second graph), and the idea is to gear up its core funds by making bond issues on the markets. So far it has raised €18bn this way. But in recent weeks it has really been struggling to raise the money as the price of its bonds has been falling since September. It had to postpone an issue and there are even rumours that it had to buy its own debt to shore things up, which rather defeats the object of the exercise. The notion that the EFSF can borrow hundreds of billions seems for the birds.

If the EFSF cannot borrow significant amounts of additional money it can only be a marginal player. So how else can Europe shore up its rescue operation? There are really only two broad options. One is that in some way or other Germany uses its borrowing strength to help the rest of Europe. The other option is to print the money.

The realisation that only Germany is strong enough to tackle – let's not say solve – Europe's sovereign debt crisis has led to the sharp change in German policy evident over the past 10 days. As Angela Merkel has sketched, to save the euro Europe has to move to a fiscal and political union. This is not the place to comment on the various political difficulties in the path of such a venture; they are obvious. But from a narrower mathematical perspective, it is worth noting that the scale of European sovereign debt is such that there is a danger that even Germany is not strong enough to provide enough of a back-stop.

No one can prove it but it seems to me that German debt is trusted for two reasons. One is because there is such resistance in Germany towards guaranteeing other countries' debt that anyone buying German bonds feels that the full ability of the German economy is behind them. The other is that if the eurozone breaks up you know you will get either a strong euro run by Germany, without the weaker members, or even a return to the Deutschemark. In other words, German euros are better than Spanish, Italian or even French euros.

In any case, this will all take time. Even if there were to be agreement on the path to fiscal union, it would take years to implement. So what happens in the meantime? You move to the option to print the money. I have been looking at a paper by Hans-Werner Sinn, president of the Ifo Institute in Munich, The Threat to Use the Printing Press. His is the clearest analysis I have yet seen of the power struggle going on over the role of the ECB in supporting the eurozone sovereign debt market and it starts with this: "Fortunately, Nicolas Sarkozy is not getting his banking licence for the EFSF. The Luxembourg rescue fund is not to buy government bonds of endangered countries with freshly printed money. The ECB, however, may continue to do this."

Professor Sinn notes that two German members of the ECB council have resigned in opposition to the ECB's purchase of bonds of European countries to shore up their price in the market, and that German MPs are also hostile to this policy.

But: "The Bundestag may indeed threaten to block the use of the EFSF rescue funds with further decisions in future should the ECB continue its bond-purchase programme, but ultimately the ECB is in a stronger position. It is the master of public finance in the euro area, and it can always start up its own rescue machinery if it deems the rescue efforts of the international community insufficient. It determines who is rescued and when and where, not the Bundestag or any other authority in Europe."

He notes that the ECB has been supporting Europe's periphery for four years by printing the money to support their banking systems and to finance much of their current account deficits. Since September it has actually been withdrawing funds from the German banking system, while continuing to flood money towards the periphery. He concludes: "The European parliaments have no control over this game. The European Central Bank Council is the true economic government of the euro area. As long as it retains its power, it can threaten the parliaments of the eurozone with the printing press and enforce comprehensive rescue measures, up to and including a transfer union."

The markets, of course, know all this. The danger is that the ECB ends up with more and more dodgy sovereign debt on its books and the eurozone faces an even greater catastrophe as and when these countries default.

Meanwhile, you can see why the premium demanded by buyers to hold all euro-denominated debt, bar Germany's, is climbing by the day. I know we are damaged by the cross-fire but the UK owes a huge debt to John Major for keeping us out of the euro in the first place and Gordon Brown for resisting Tony Blair's efforts to get us in later. Phew!

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies