Hamish McRae: The Governor of the Bank of England has no idea what interest rates will need to be in three years' time

Economic View: If we get three years of above-trend growth we are going to feel pretty chipper

It is, as the baseball legend Yogi Berra put it, "like déjà vu all over again". The Bank of England's Inflation Report again acknowledges that the economy is growing much faster than it thought, and the Governor, Mark Carney, again asserts that interest rates won't go up any time soon and when they do it won't be by much. OK, maybe "asserts" is unfair, let's say "guides".

The new bit of guidance, that Bank rate will be "materially below the 5 per cent set on average" before the financial crisis, should be taken with the same scepticism as the Bank's forecast last year as to when unemployment would reach 7 per cent, the trigger point for an increase in rates. And yes, I know that was expressly intended not to be a trigger, but that was what the markets jumped on as the likely moment when rates would start to move.

The basic point here is that the Governor and the members of the MPC have no idea what level interest rates will need to be in three or more years' time. None. If that seems a bit harsh, consider this: could any member of the MPC have conceived in the summer of 2007 when rates were 5.75 per cent that in less than two years' time they would be 0.5 per cent?

Actually it is perfectly plausible that rates will be somewhat lower in the future than they have been in the boom years of the decade to 2008. There are a number of reasons why. For a start, governments around the developed world will seek to hold down their borrowing costs. The posh expression is "financial repression"; the more honest, "cheating less-sophisticated savers". Households, lured into the borrowing spree, are still paying down debts, so you don't need higher rates to curb their borrowing. Companies, suddenly squeezed by the banks, will be careful about getting into hock again. And banks themselves have been forced to pare down lending by capital and other requirements.

But that is only a guess. It is, conversely, quite possible that we may be in the early stages of another bubble in property and other asset prices. If that proves right, expect the asset prices to feed into current prices over the next three years. So if inflation at a consumer level goes back to, say 4 per cent, we may very well need rates above 5 per cent to curb it.

The reassertion of the importance of the inflation rate is welcome, but remember that the experience of the past decade has taught us about the huge cost of over-loose monetary policies, even when on the official measures inflation looked acceptable. There is an argument that one could use regulation over the supply of credit, rather than the price of credit, to stop bubbles occurring. But regulating the supply of credit, rather than its cost, creates distortions that damage the financial system in other ways.

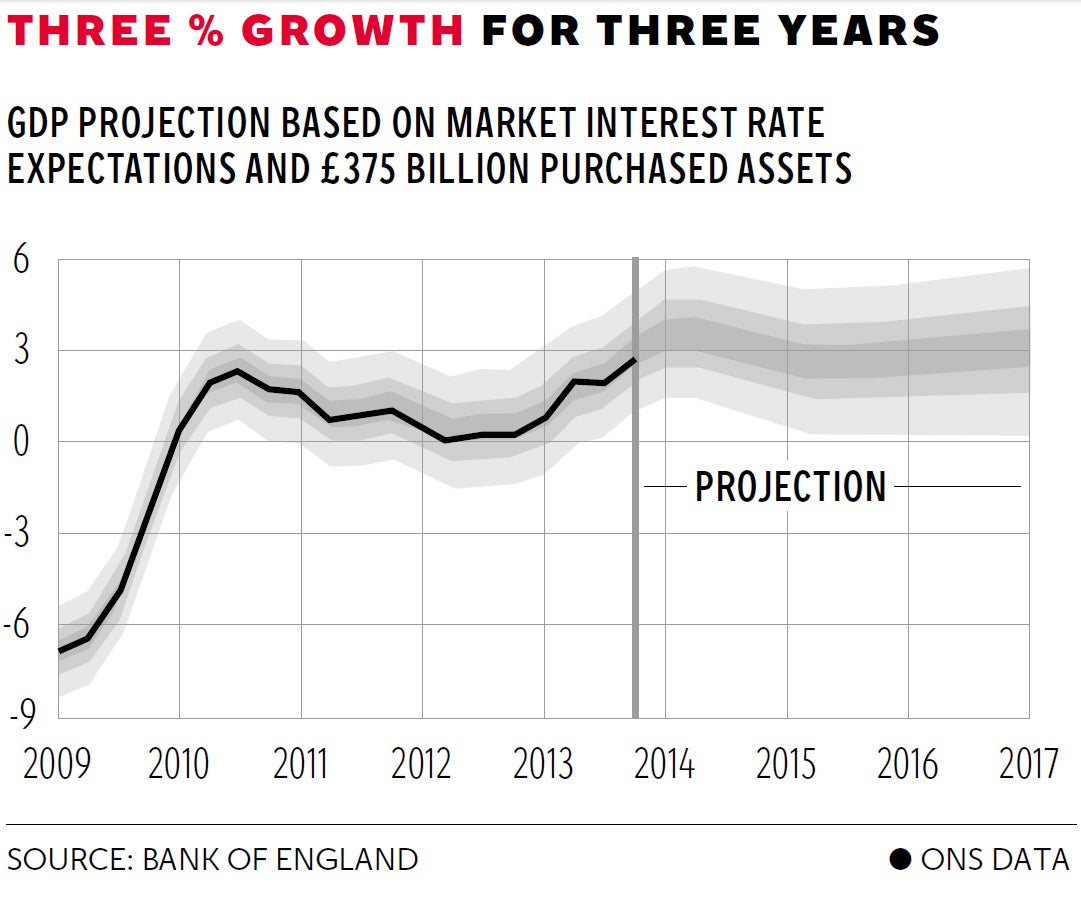

Have a look at the graph, the fan chart for growth over the next three years taken from the Inflation Report. The Bank expects that growth will be around 3 per cent a year through to the end of 2016, with the obvious possibilities that it might be higher or lower. But let's assume that this will turn out to be broadly right. Trend growth is 2.25 per cent, maybe a little more. What will three years of above-trend growth do to our attitudes about working, saving and spending? It may be that any latent animal spirits will be crushed by higher taxation, for the scale of the spending cuts necessary to eliminate the deficit look daunting. There may have to be higher taxes after the election. There may be some further economic shock out there. But if we do get three years of above-trend growth we are going to feel pretty chipper. The party will be going good and the task of the central banks will be to take the punchbowl away.

This leads to a wider question, not just a British one: what is the likely shape of the cyclical upswing that most of the developed world is experiencing? We cannot know but we can guess. Think global. The present cyclical upswing must have some way to run. Fiscal policy is two-thirds of the way back to normal – only half way here, but two-thirds in the US and fine in Germany. But the path to normality for monetary policy has only just begun. As for structural policies, that huge bundle of very different things from labour market reform to sorting out the banks, there has been uneven progress but nevertheless progress.

Put this together and you could conclude that the fundamental conditions for balanced growth are being re-established. There are places where policy is sub-optimal. Europe is the obvious example, not because of the clever patching by the ECB, but because of the flawed engineering of the system itself. But that cannot be fixed until there is some realignment of the members of the eurozone and that cannot be done yet. It needs another crisis. But to focus on the rigidities of the world economy is to neglect its flexibilities. You can see that in the UK, for we have managed to get growth going with credit flows much smaller than five or six years ago.

So the world economy should have several decent years to grind away at the debt burdens at every level and begin to restore living standards across the entire developed world. That seems to be the common-sense message of the Inflation Report. Meanwhile, I suggest that for guidance you don't listen to what the Bank says but watch what it does.

Or as Yogi Berra said: "You can observe a lot by watching."

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies