Hamish McRae: Ukraine lags far behind even the poorest European state but there is a way forward to a wealthy future

Economic View: The EU takes over a quarter of Ukraine's exports, but it could be so much more

What would it take to turn Ukraine into a successful economy? It is certainly in the overwhelming self-interest of the West, and indeed of Russia, that it should be so. Yet while in many senses the country has made some real progress over the past decade, the tantalising possibility is that it so easily could be doing much better. The prime task for the EU is not to give the country handouts – though it will need substantial emergency funding – but rather to nudge it towards rapid and sustainable growth.

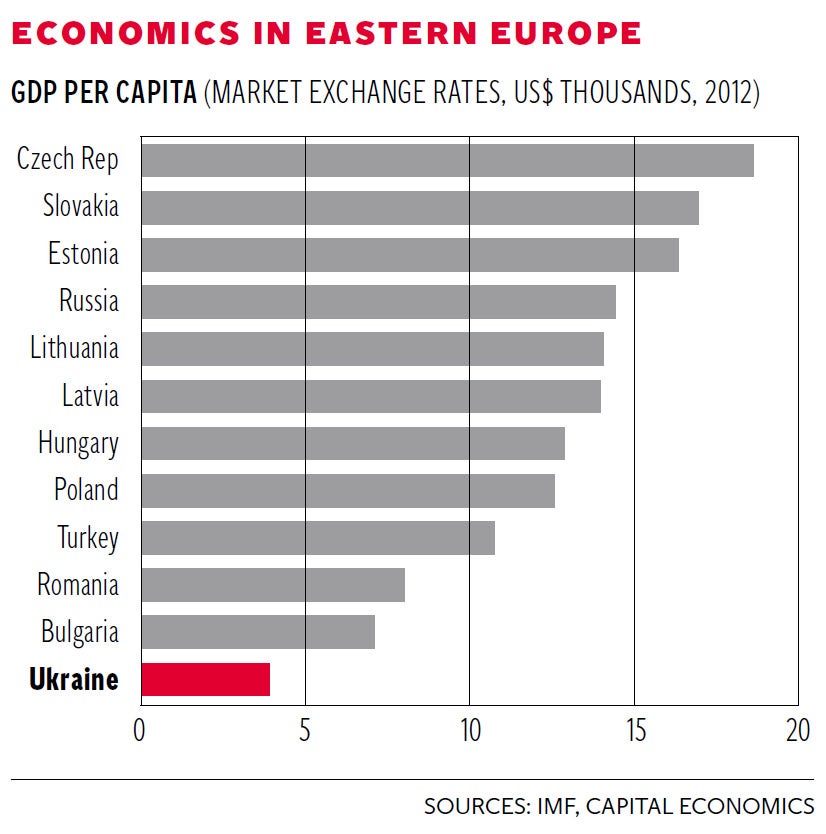

The background is that while the country is potentially rich, like the other parts of Soviet bloc it suffered a decade of disruption following the break-up of the Soviet empire. Then, from the late 1990s through to the financial crisis of 2008, it enjoyed rapid but uneven growth. But it was particularly devastated by the fall-out from that, suffering worse than the eastern European states of the EU, and worse than Russia. Since then there has been a recovery, but an uneven one. As you can see from the graph, GDP per head, at least as officially measured, remains far below even the poorest EU members, Bulgaria and Romania. It is also lower than Turkey, and much lower than Russia. The gap in actual living standards will not be as great, certainly in the western and northern regions, for official data understates the level of economic activity. But there is no escaping the harsh fact that Ukraine is at the bottom of this league table, and far below where it should be. There is a wide gap and the EU can help to close it.

The first thing that has to be done is emergency funding. There is widespread agreement that the country needs money fast, but rather less so on the quantity. Estimates range from $15bn (£9bn) to $25bn. As always in this sort of crisis, credibility matters as much as hard numbers, for a sizeable EU/IMF support package coupled with the establishing of a credible government would attract capital inflows. There is a current account deficit to be financed, running at $15bn a year, but were capital to flood back into the country, reversing the flow of recent weeks, the absolute amount of support need not be much more than that. Yesterday the central bank promised measures to stop the capital flight. We will see whether these work.

Coping with the emergency is straightforward enough. Nudging the country towards the wealthy future that is within its grasp is vastly more complicated. At the moment the EU takes over a quarter of Ukraine's exports, roughly the same as Russia, but it could be so much more. That is why the proposed trade deal matters. What it has to offer the EU is not just raw materials and agricultural produce, though those are the two areas of excellence that usually spring to mind. (Did you know, by the way, that Ukraine is the world's largest exporter of sunflower oil?) It can offer a well-educated and sophisticated workforce that is already performing well in modern industries such as information technology. Essentially Ukraine can be for Europe another Turkey: a fast-growing country on its borders than can do things that the EU countries can do but at lower cost. The trade deal would make it easier for the market to signal what those activities are.

There are, however, two less comfortable issues. One is the economic relationship with Russia; the other, governance. On the first, it is all very well for the EU to open its markets to Ukraine, and in practice the trade borders are pretty open already. But this has to be done in a way that does not antagonise Russia. In economic terms the country sits between two trading blocs. It is not either/or. Economic progress depends on trading with both. Somehow the politics have to be consistent with the economics. I suppose the obvious model would be Finland during the Cold War, a country that was non-aligned politically but operated a Western economic model. How you engineer that is another matter.

That leads to the question: how do you push the country towards a Western economic model? The potential impact of the trade agreement is helpful, not just because of the direct impact of increased exports to the EU. It is because it would also nudge the Ukraine towards Western standards of corporate governance. Estimates vary as to the extent to which corruption has damaged the Ukraine economy and it may not make much sense in trying to make those calculations. What we do know – and have seen even more visibly in Russia – is that any activity or behaviour that undermines the ambition and energy of the educated middle-class is a drag on growth. It distorts resources and pushes activity into rent-seeking behaviour. Clever people spend their energy on getting a larger share of the cake rather than on increasing the size of it in the first place. Russia has at a macroeconomic level got away with a pretty sub-optimal economic system thanks to its vast energy reserves and exports. But it has done so at the cost of a skewed economy, with energy and raw materials supplying 80 per cent of its hard currency earnings, an even higher proportion than in Soviet days. Ukraine does not have that option, and many would say a good thing too.

How do you change a system? How do you deal with corruption? There is a limit what can be done from abroad but there is a rough template, provided by the reform programmes of eastern Europe over the past two decades. There are several elements to this, starting with macroeconomic stability: a more-or-less balanced budget and sound banking and monetary policy. Eastern European countries have also put through a series of regulatory and legal reforms, which have greatly improved corporate governance. As a result we have an arc of rising prosperity among the EU's new member states. Changing business culture, though, is tough, particularly when it is intertwined with political culture. All one can say is that others have done it. This is not a journey without maps.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies