Hamish McRae: You'd better sit down – stock markets are doing rather well

Economic Life

Whisper it low, but stock markets around the world have had the best January for 18 years. The MSCI all-country world index is up 5.8 per cent, while bank shares are up nearly 10 per cent – let's call that the Fred Goodwin memorial rally. And all this has happened despite the ongoing travails of the eurozone, travails that will doubtless continue for many months yet.

This revival of optimism does of course follow a profound loss of confidence last year. It is easier to have a great leap forward if you start from a fair way back. Still, it is marked enough and widespread enough to be worth respecting, and from our own narrow national perspective it is welcome.

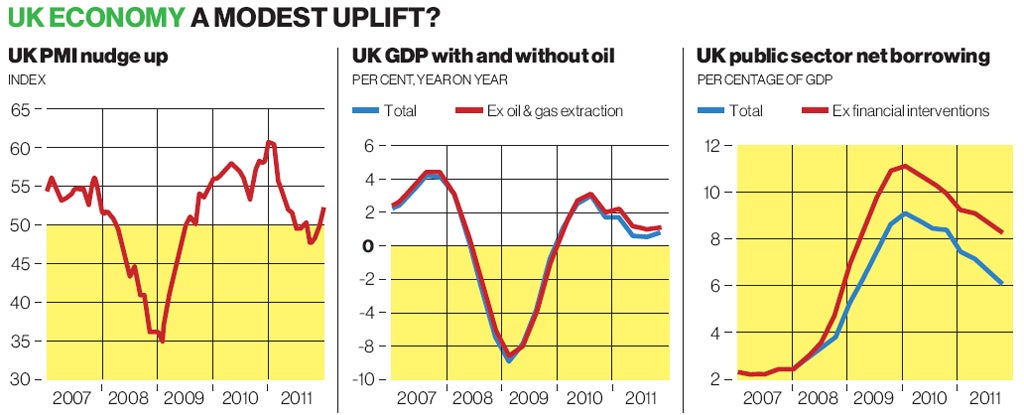

This recovery in confidence has been spurred by an uplift in industrial sentiment. It is pretty widespread, but you can see our own take on this in the first graph.

The UK January purchasing managers' index for manufacturing came out yesterday and surprised by climbing from 49.7 in December to 52.1. Any reading over 50 suggests growth and this is the highest since last May.

As you can see, this is not wild optimism by comparison with the days immediately post-recovery, but expansion is better than contraction. Companies in other countries have reported a similar lift in their mood.

This is an encouraging backcloth to our government's financial position, highlighted by the Institute for Fiscal Studies' Green Budget just published. The IFS is admirably apolitical as well as being hugely competent, so its analysis should be taken seriously.

Its paper is reported elsewhere, but it might be worth making a couple of points here. The most important one is that the Government is still on its (downwardly revised) course for correcting the deficit; indeed, it is running a little ahead of its target for this year, thanks largely to a £3bn underspend by government departments.

That leads into a debate as to whether the Government could or should ease up a little on its debt-cutting programme. The issue is whether the modest extra amount of money it might put into the economy would be offset by any negative impact on business confidence, or even some rise in market interest rates.

You can argue this either way. My own feeling is that £3bn in an economy of £1,500bn is no big deal. But there could be a case for using the money saved by the fact that the Government is borrowing more cheaply than it expected to make some modest tax cuts, particularly for the low-paid. The whole 50 per cent top tax rate matter needs to be tackled, but since this is revenue-neutral (or may even cut revenue in the longer term) that is a political rather than an economic matter. The present debt-reduction path, by the way, is almost exactly the same as that set out by the former Chancellor, Alistair Darling.

The most intriguing issue is the way the tax revenues have continued to come in on track despite lower-than-expected growth. One explanation could be that growth is higher than recorded but it will be several years before we have the full data. In any case, growth has been depressed by a fall in the value of the output of North Sea oil and gas. The middle graph shows how, were it not for this decline, GDP last year would have been growing at around 1.4 per cent, still slow of course, but not quite as slow as the 0.9 per cent number officially recorded.

The other point to make is that the UK deficit is being cut by the profit the Government is making from its support for financial institutions. The effect is shown in the right-hand graph. The overall debt of the Government has been increased by having to take control of Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) and near-control of Lloyds Bank. But, as Simon Ward, economist at Henderson, notes, last year the Government made a total £33.5bn of "profit" from its financial interventions. Of that £19.6bn was the surplus of the banks it supported, while a further £8.1bn came from the profit the Bank of England was making on its asset purchase facility.

Now, it is also true that the Government is standing on a loss on its shares in both RBS and Lloyds, and that money had to be borrowed for it is part of the national debt. It would be an accounting device and would not change the reality, but you could book the profit from the interventions and argue that the deficit is running a couple of percentage points lower than officially reported.

We are set on the glide path to the budget on 21 March, but there is a lot that can happen between now and then.

The conventional view, reflected by the IFS, is that the risks are on the downside. That may well prove right, but it remains true that the strategists at the various fund management and investment banks around the world are switching to a more positive position.

There is a general optimism about emerging markets and a sense that eventually the US economy will show somewhat better growth. You can just say this is the result of a conviction that the world's central banks will simply print the money to keep growth going and worry about inflation later. But the best start for shares since 1984 has concentrated minds wonderfully.

The generally bearish mood of four weeks ago has flipped. How that helps the UK taxpayer, still facing years of chipping away at that mountain of debt, is another matter.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies