The developed world is ageing – is this necessarily a problem?

Economic View: The positives of an ever-larger army of older people has been rather neglected

It is the age of the old – just ask 97-year-old Maria Franca Fissolo, the £15bn widow of chocolate tycoon Michele Ferrero. With all the emphasis on the way demographic change affects, and in many cases damages, economic performance, the positives of there being an ever-larger army of older people in the world has been rather neglected. However several studies out in the past few days have focused on the varied implications of the shift of economic power to older people, and they deserve a wider airing.

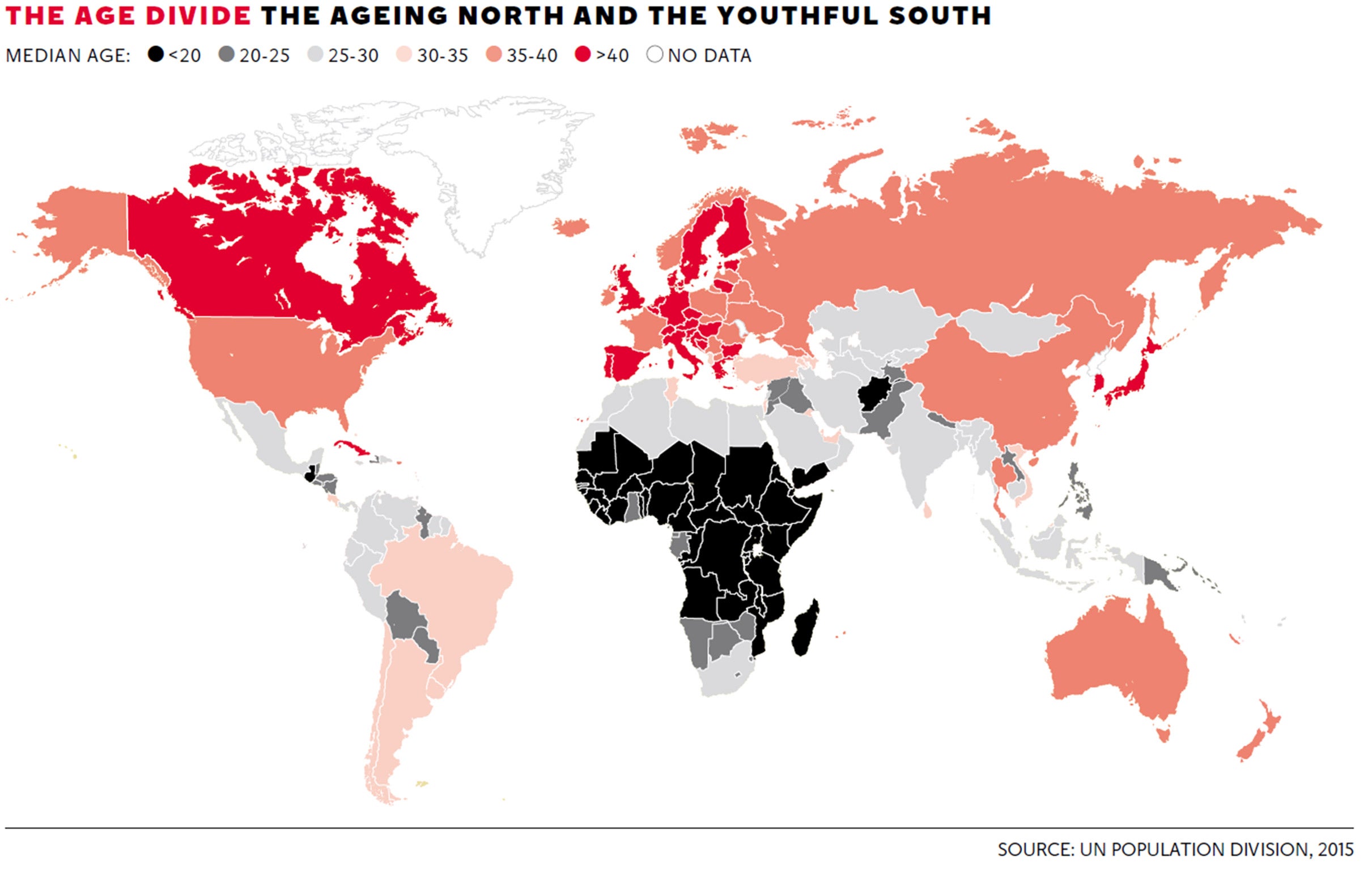

First, the big picture. As you can see from the map, below, the contrast is between an old developed world and a young emerging world. But there are twists to this. Within the developed world, the US and UK are ageing relatively slowly. Within the emerging world, China is ageing much faster than India, while Africa is the youngest continent and will become yet younger. That leads to the question as to whether Africa is able to educate its young sufficiently well to be an economic asset, quite aside from the social and moral obligations to give the next generation the best possible start in life.

The graph comes from a recent study by HSBC, which notes that while many of the changes will take place gradually over the next 50 years, others will have effects during the next 10. For example during this coming year, 2016, the world’s population will grow at the slowest rate for 65 years and the median age in the developed world will rise above 40. It notes that “smaller populations mean less demand and less potential output”, a point that is now widely appreciated. The big question is to what extent these negative aspects can be offset by later retirement, higher participation rates, and inward migration.

However, though the old may be or at least become an economic burden, in the UK at least they are doing rather well, as a couple of studies show. One, by the Resolution Foundation, today reports on how the share of wealth owned by the recently retired has passed the wealth of the under-45s. The big influence here is rising house prices. It observes: “Households headed by someone aged 65-74 now hold more wealth, despite there being more than twice as many households headed by someone aged 16-44. Recent retirees account for almost a fifth (19 per cent) of the UK’s total household wealth, despite making up just 14 per cent of all households.

“The stark generational wealth divide has grown since the financial crash, as a result of the recently retired being relatively protected in a downturn where house prices had a swift recovery, while real wages took six years to start increasing again. The over 60s were least affected by the UK’s pay squeeze.”

This point that quantitative easing has favoured the old rather than the young was reflected in another paper this week, this time from Canada Life. It noted that retired people have increased their spending by 53 per cent over the past 10 years, with spending climbing faster than disposable income, up 43 per cent. Non-retired households have increased spending by only 27 per cent since 2005.

So the old are doing rather well, helped in Britain by the “triple lock” on pensions as well as rising asset prices. What then?

The image, loved by the ad agencies, of comfortably off couples eyeing the sunset from the deck of a cruise liner, has some rationale behind it. The Canada Life study found that retirees had increased their spending on leisure activities by 56 per cent over the past decade, while the “fun” spending by working households was up only 9 per cent. These numbers are in money terms, so allowing for inflation, their spending on leisure is actually down.

Taken together, then, the picture of a comfortably-off old and a striving, often struggling, young holds good. But there is a twist. The old inevitably have eventually to give away their money, as in the old saying “you cannot take it with you”. For most people this is really a matter of helping children with their deposit on a mortgage, or grand-children’s university costs. But it is also, particularly in the US and increasingly in the UK, a matter of philanthropy. As the government retreats, people with money have to move in.

The contrast between the US and continental Europe is particularly stark. It is hard to get a fix on charitable donations internationally, but some calculations by the Charities Aid Foundation a few years ago made it clear that the US was by far the most generous, giving 1.69 per cent of GDP, followed by the UK with 0.73 per cent, followed in turn by Australia at 0.69 per cent. By contrast Germans give only 0.22 per cent of GDP and the French 0.14 per cent. These figures, I should make clear, do not include emigrants’ remittances – money given by people working in developed countries to their families back home. In the US these are around another 0.7 per cent of GDP.

This leads to the question of whether philanthropic giving might go quite a lot higher still, particularly here in the UK. The US has a long-established tradition of philanthropy, driven by 19th-century magnates such as Andrew Carnegie, and the Rockefellers – a tradition carried on by Bill Gates and now by Mark Zuckerberg of Facebook. But mostly it is the old that give, not the young – because they have the money. In Britain philanthropy has yet to be as celebrated as it is in the US, but the combination of the rising wealth of the old and rising need for something to replace squeezed government funding creates the perfect opportunity.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks