Britain has lost a decade of growth and it is never coming back, says Institute for Fiscal Studies

Calculations by The Independent suggest every person in the country is today around £4,000 worse off than they would have been if the British economy had continued growing at its rate seen before the 2008-09 recession

Britain has now experienced a “decade without growth” according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies and the latest official projections in the Budget suggest this lost income will never be recovered.

In its response to the Budget the respected think tank said the Office for Budget Responsibility’s new analysis paints a bleak picture of the UK economy, with weak GDP growth by historical standards and very disappointing wage increases over the next five years.

“What the OBR is saying is that despite that truly dismal record all of the productivity – and with it earnings growth – we would normally expect has been lost forever,” said Paul Johnson, director of the IFS.

“This remains the big story of the last decade – a decade without growth, a decade without precedent in the UK in modern times”.

Calculations by The Independent suggest every person in the country is today around £4,000 worse off than they would have been if the British economy had continued growing at its rate seen before the 2008-09 recession.

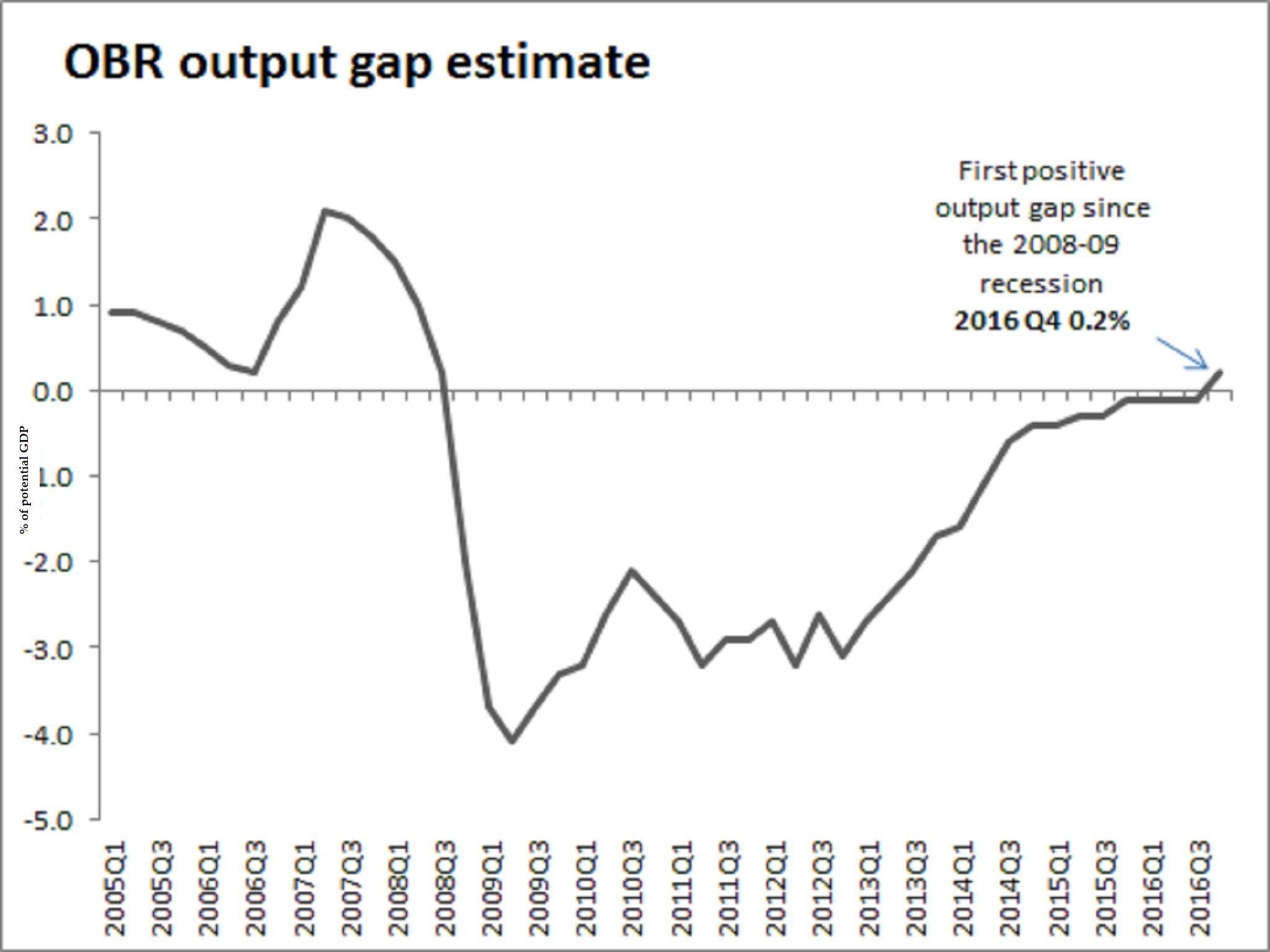

The IFS pointed out that the OBR now estimates the so-called “output gap” of the UK economy turned positive in the final quarter of 2016 for the first time since the UK was on the verge of slipping into the recession in 2008.

The output gap refers to the amount by which the economy can grow without generating harmful inflation, meaning a positive output gap for an economy like Britain that is still well below its previous trend growth rate, combined with a weak forecast for potential productivity growth, means any lost output is likely never to be recovered.

In its latest forecast the OBR pencils in a 0.2 per cent of potential GDP positive output gap for the final three months of 2016, up from a negative 0.1 per cent output gap in the third quarter of the year.

Negative positive

According to the OBR the output gap has been minus 0.1 (essentially closed) since the final quarter of 2015 but this is the first time that the Treasury’s official forecaster has put the figure in positive territory.

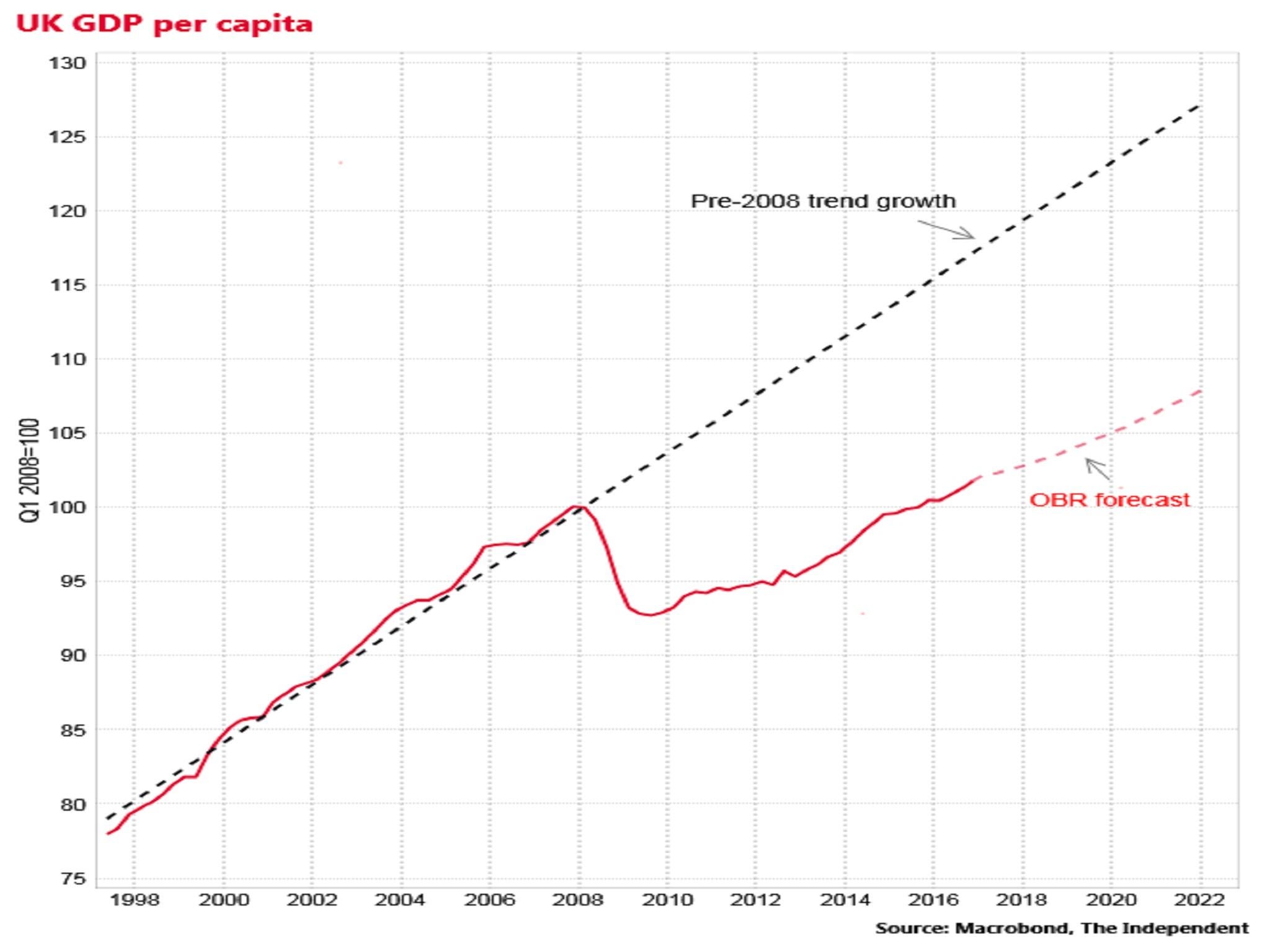

In the wake of previous recessions in the 1990s, the 1980s, the 1970s and the 1930s the UK has always got back to its trend GDP per capita output levels through rapid post-crisis growth. But the OBR thinks that this time the damage of the recession is permanent and that per capita GDP growth will actually grow now more slowly than the pre-crisis rate.

The UK’s per capita GDP, or national income per person, is just 2 per cent higher than it was in 2008 according to the latest official estimates. If this had grown at the pre-2008 rate it would have risen by 17 per cent over that same period.

Gone for good

On the OBR’s latest forecast GDP per capita by 2022 will be just 8 per cent above 2008 levels, rather than the 27 per cent implied by the pre-2008 trend.

The weakness of growth in GDP per person is the underlying reason wages have been so weak for the past decade.

The Resolution Foundation think tank, using the OBR’s latest wages projections, calculates that Britain is now facing its worst decade of real pay growth since the Napoleonic Wars some 210 year ago.

Real GDP per capita in the final quarter of 2016 was £7,157. If it had grown at the pre-crisis rate it would today be £8,229.

On an annual basis that means everyone in the country is around £4,300 worse off than they would have been if the pre-crisis growth rate had continued.

By 2022, under the current OBR forecasts, that loss per person relative to the pre-crisis trend grows to £5,400.

The OBR actually thinks the output gap will slip back to zero in 2018 and turn slightly negative again in 2019 and 2020 as the economy slows due to the negative impact of Brexit. But it remains close to full capacity over the five year forecast horizon.

Some economists are concerned by the assumption of forecasters such as the OBR that the output gap is zero and that the UK’s lost output from the 2008 recession can never be regained.

Simon Wren-Lewis, Professor of Economic Policy at the Blavatnik School of Government at Oxford University, has argued this is in danger of becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy if policymakers behave as if fiscal stimulus will simply result in damaging inflation, rather than spurring sustainably faster catch-up growth.

Recessions are generally assumed by economists to open up large output gaps in economies.

The implication of a positive output gap, along with estimates for a weak forecast for trend productivity growth, for the UK is that there is no scope for quicker catch-up GDP growth for the UK to regain all the income we have lost relative to where we would have been in the absence of the 2008 crisis.

The output gap cannot be directly observed, only estimated with the help of various surveys and judgements by forecasters.

The Bank of England does not publish its own estimates of the UK's output gap, but the Bank's figure is estimated to be below 0.5 per cent of GDP, suggesting it shares the pessimism of the OBR over the ability of the UK to return to its previous trend growth path.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments