The secrets of our supermarkets

Brain scans, eyeball cams, crowd-modelling software: big stores use it all to get our cash. As an Asda executive reveals the tricks of a billion-pound industry, Simon Usborne takes an educational trip down the aisles

You could almost hear the static as the suit from Asda squirmed in her seat. In a few seconds on the Today programme, Sian Jarvis, the supermarket’s head of corporate affairs, had undermined her claims to care about the health of her customers and let slip one of the secrets of a multi-billion-pound industry.

The executive, a former Government communications chief, tried to spin herself out of a public relations hole after she revealed that one in three Asda checkouts “are what we call guilt-free checkouts”. Accordingly, Naughtie suggested, “two out of three are guilty”.

The admission came during a debate about new health guidance labels that will appear on packaging from next year. What good are they, Naughtie asked, if supermarkets bury checkouts under confectionery designed to lure small hands and parent pounds?

Jarvis insisted “guilt-free” was merely “a term that’s commonly used in retail”. But it was too late, and her “guilt” gaffe quickly invited scorn in the industry and among public health professionals. Whatever the damage, she had already opened a door to the arcane science of supermarket psychology. To the designers of the modern store, shoppers are lab rats with trolleys, guided through a maze of aisles by the promise of rewards they never knew they sought. In Britain, we spend £160m a day on food and the “big four” – Tesco, Sainsbury’s, Asda and Morrisons – fight with ever more sophisticated weapons for every penny they can get.

Simeon Scamell-Katz is the de facto master of this science. A leading global consumer analyst and the author of The Art of Shopping: How We Shop and Why We Buy, he says the challenge for supermarkets is to break habits. “Shopping is so ritualised that we walk around like zombies,” he says. “We’re incredibly patterned in what we do.”

Scamell-Katz uses brain scans, footage of volunteer’s eyeballs, live bird’s-eye views of supermarkets and crowd-modelling software to observe and analyse this behaviour, helping retailers devise ways to nudge us into spending more.

The consultant to dozens of leading stores says Jarvis was guilty herself – of “ineptitude” – and that he had not heard “guilt-free” used to describe checkouts. To him, they are “impulse areas” or “golden zones”. From these terms to “environmental envelopes” via “gondola ends” and “signpost brands”, he helps map the laboratory that is today’s supermarket, where selling has become a science.

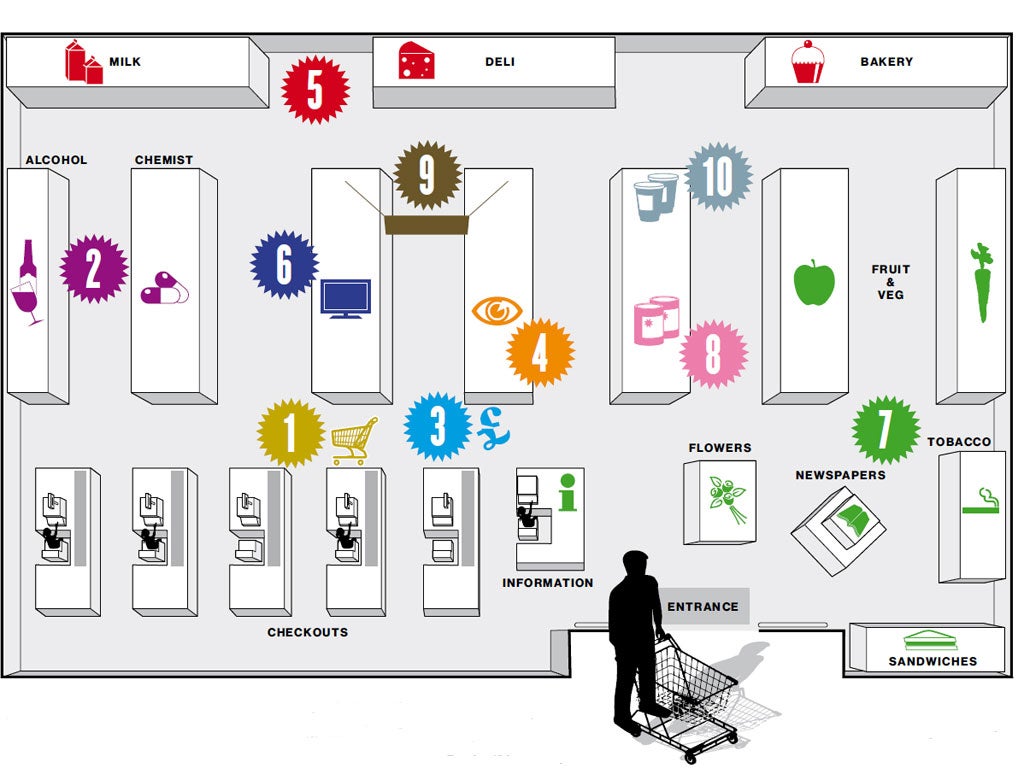

An insider’s guide: the tricks of the rat-trap store

1. Golden zones

Also known as “impulse areas” or “grab zones”, they include “checkout arrays” or “walk-through queues” filled or lined with treats. “They’re not there for pleasure,” Scamell-Katz says. “They’re there to make money and the best way to do that is with products that are bought as a reward for the task you’ve just completed.” If we were rats, the end of the shoppers’ maze would be piled with squares of cheese rather than chocolate bars.

2. Shop-in-shop

“Wooden floors and shelves and nice lighting can be suggestive of a different environment in the wine aisle,” Scamell-Katz says. Tests show we buy more expensive items with bigger profit margins if, he adds, supermarkets “sell the dream”. “You’re not doing it if you put indulgent products like skin cream in a cold warehouse with harsh lighting, so you offer visual cues of comfort and beauty.”

3. Gondola ends

Also known as “endcaps”, these are the exposed, short blocks of shelves at the ends of aisles where special offers are typically found. We have now become so habituated to expect them, Scamell-Katz says, that when US chain CVS started filling endcaps with undiscounted products under signs made to look like promotions, sales duly increased.

4. Buy level

Brands often pay supermarkets listing or placement fees, which vary according to the prominence of the desired shelf. Logic dictates that eye level, a standard 1.6m from the floor, is “buy level”, but Scamell-Katz used eye-tracking cameras on volunteers to show “we naturally look lower than eye-level to somewhere between waist and chest level”. Eye level became grab level and when Scamell-Katz showed his research to his then client, Procter & Gamble, it requested lower, cheaper shelves. Sales increased before curious supermarkets realised what was happening and changed their listing fees structure.

5. Traffic builder

Ever wondered why milk and bread are always way at the back of the store? The theory goes that placing essentials away from the entrance means we are exposed to more potential purchases and offers on the way. Scamell-Katz’s research shows these distraction tactics can be fraught because shoppers arrive at a store with a mission from which they are reluctant to be diverted. Forcing them to walk further for a pint of milk can engender bad feelings. A study at a supermarket petrol station showed quick-buy essentials placed close to the entrance made shoppers more likely to return to the main store for their weekly shop.

6. Power aisle

Sometimes known as “action alley”, this can be a central aisle or prominent area into which one-off promotions such as TVs or DVD players can be piled roughly in their cardboard boxes. “They’re usually short-term, not continuous lines of, say, a bunch of cheap TVs,” Scamell-Katz says. Regardless of the price, the power aisle gives the impression there’s a good deal to be had there and beyond, increasing the likelihood you’ll spend more than you intended, not less.

7. Front of shop

Shopper “missions” may involve a week of supplies, the ingredients for a solo dinner, or a lunchtime sandwich. Supermarkets must try to cater to all missions, and for this the front of the store is crucial. Do it right for the sandwich-buyer, and he or she may just return on Saturday to spend £200 on the family. Shelves for sandwiches, crisps and drinks, as well as newspaper bins and flower displays also give the welcome impression of a smaller, local store. The shopfront extends to the all-important fruit and vegetable aisles. Perversely, Scamell-Katz says, this is “massively inconvenient”, adding: “You buy all the squishy things first and they get crushed under the rest of your shopping, but those abundant displays of beautifully presented carrots or exotic fruits give the impression you’ve come to a store of freshness. Some retailers in Scandinavia and the US spray a continuous mist of water over their veg so they look as if they’ve been plucked from the tree and brought to you.”

8. Signpost brands

Two-thirds of us don’t shop with a list because we’ve built a mental map of our local store. We likewise disregard aisle markers but research has shown two things: we start concentrating towards the middle of an aisle, and here we expect to be guided towards a category by the most recognisable “signpost” brands. The Heinz logo, for example, tells us we’re in tinned-vegetable country. Coca-Cola means soft drinks, and so on.

When they’re used well, signpost brands can increase sales of all products in a category. Guinness is the signpost brand for stout. When research showed customers often strolled past it to get to lager, Scamell-Katz advised the firm to place 4ft cardboard Guinness pint glasses at either end of the stout shelves. Overnight, sales of all drinks in the category increased by 23 per cent, and even by 4 per cent across all beer.

9. Environmental envelope

This encompasses the look of a store and, crucially, the visual cues that scream “discount” or “special offer”. It includes posters in car parks and, in-store, hanging signs and shelf signs, sometimes called “aisle violators”. “We’ve learned that people rarely even look at them,” Scamell-Katz says. “But they suggest that deal activity is going on. We told an electrical retailer to stop changing the signs every week because it was a waste of money. They didn’t believe us so we reprinted the signs in the same colours but without words. It made no difference to sales.”

10. Range reduction

We think choice is king, but arguably we don’t know our own minds. The average household uses 300 products in a year. A large supermarket stocks 80,000 products. Sometimes less can be more. Danone, the yoghurt people, were told by consultants to cut their range by 40 per cent. They agreed. Only 15 per cent of shoppers noticed, and sales increased 20 per cent.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments