How two British shipwrecks still fascinate us decades later – and what we can learn from them

Tragedies that befell sailors decades or even centuries ago still fascinate and move us, showing, Godfrey Holmes says, the enduring power of the oceans over our imagination

Two ships, two missions, two follies, two groundings, two sinkings and two frightful disasters. One was so long ago that engraving had to do the job of photography; the other was recent enough that some people alive today will have heard about it from their parents. In one, a foreign ship came to grief in British waters; in the other, a British vessel went down in foreign waters, and down she stayed.

First to Texel, safe haven, population 13,500: the largest of the West Frisian Islands off the coast of the Netherlands in the Wadden Sea. Today it is a magnet for Dutch cyclists, walkers, swimmers and riders (the latter an important reminder that Texel is the only known place where an entire navy was defeated by men on horseback, which is another tale altogether).

In June 1743, a 700 ton vessel, VOC Hollandia, set sail on her maiden voyage bound for Batavia, the capital of the Dutch East Indies, now known as Jakarta. In any study of trade between Europe and Asia throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, the Dutch East India Company is pivotal, shipping everything from nutmegs and cinnamon to coffee and tobacco, porcelain to rubber. And that is what VOC stands for: Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie.

Yet on this prestigious occasion, Hollandia, being of brand new and bold design, an impressive 42 metres in length, was carrying a particularly special cargo: not only many VIP passengers but also 130,000 coins. Most were “pillar-dollars”, cut to represent smaller denominations, but among the haul were also highly valuable Mexican and Guatemalan silver coins.

Hollandia’s captain must have been nervous therefore, as he headed for Brittany through rough seas. Perhaps he was aware too that just 36 years before, in 1707, at least 1,550 men had perished in the same waters, haplessly drifting towards the Scillies aboard four Royal Navy warships: the Firebrand, the Romney, the Association and the Eagle. (Indeed, square mile for square mile, the treacherous Scillies are probably responsible for more of the world’s estimated 159,000 shipwrecks than anywhere else.)

Remember, these were the days before the invention of reliable navigation instruments; still before the erection of most lighthouses.

Sure enough, like those earlier ships, the Hollandia was blown off course, scarcely six weeks after setting sail, on a blustery 13 July. And it too came to grief off the Isles of Scilly, striking the notorious Gunner Rock, going down just off Annet, an uninhabited nature reserve just 54 acres in size, 20 miles from the Cornish coast.

Nobody lived to tell the tale.

Miraculously, in 1971 a London attorney called Rex Cowan discovered the Hollandia’s wreck, along with its bronze cannons and some of its treasure. Unusually, he was using a proton magnetometer, allowing him to test the Earth’s field of magnetic resonance, which in the process reveals every slight variation across that field – including ferrous objects embedded in land or sea.

However, it is now time to turn to the anniversary of a sinking far further away and to consider the watery grave awaiting an equally emblematic vessel. This was a calamity that was far more preventable.

State of the art flagship and battleship, the HMS Victoria – named in named in honour of the Queen’s impending Golden Jubilee in 1886 – was launched at a cost of £845 from Elswick on the Tyne. When she headed for the Mediterranean in June 1893 for training exercises, she had already endured one major mishap – a grounding at Platea, off the Greek coast, with Captain Maurice Archibald Bourke having permitted members of his crew to misplace the buoys that might have saved him from some very shallow waters.

On that first cataclysmic day, 29 January 1892, no full tide – indeed nothing at all – would get the extraordinarily long (100 metres), extraordinarily heavy (11,200 tons) Victoria afloat again. Jettisoning 483 tons of coal, and calling for a tow from three other Royal Navy frigates, somehow the Victoria – its bottom damaged, three of its compartments seriously damaged – resumed its voyage on 4 February, limping into the new Hamilton Dock, Malta, for repairs. Bourke, despite being severely censured, retained his command.

At the dawn of a second catastrophic day, 22 June 1893, Bourke and his contemporaries, among them Captain Jenkins on the Collingwood and Captain Markham on the Camperdown, were lined up like tin soldiers ready for an experimental manoeuvre – a very tight one at that. It was their misfortune to be in the hands of Vice Admiral Sir George Tryon, Commander of the British Mediterranean fleet: an obstinate, overbearing man with some very peculiar traits and strategies.

Tryon was deliberately taciturn and unapproachable – the better, he thought, to assert the superiority of his rank. The better too to outdo “inferior” French and Italian navies also cruising the vital Mediterranean; and the better to force his officers to think on their feet.

Inexplicably – and at a time when signalling remained primitive, based as it was on a mixture of flags, semaphores and lamps – Tryon wanted the two columns of his fleet to turn, uniformly, a full 180 degrees, first towards each other then (so the theory went) retracing their prior course. His 11 Captains – with Tryon himself menacingly aboard the Victoria – were to do this whilst positioned a mere 1,100 or 1,200 metres from each other, even though a gap of 1,800-2,200 metres might have been considered a safe bare minimum.

Markham hesitated. Surely Tryon had confused radii for diameters? Surely he had issued the sort of order likely to be revoked any minute? Perhaps Tryon really intended the convoy to turn 60 degrees to port, then 60 degrees to starboard, before resuming its original course?

Tryon however, was getting impatient. Fearing humiliation – his colleagues also hesitant to defy their esteemed commander – Markham aboard the Camperdown conceded, swinging towards the fated Victoria, despite believing he cannot avoid hitting her. Even so, the Victoria – built before the installation of automatic bulkhead doors – has many proven stabilisers. Perhaps Bourke is a more gifted captain than he has previously demonstrated?

At the last, both lead vessels went straight into reverse thrust. But it was all too late.

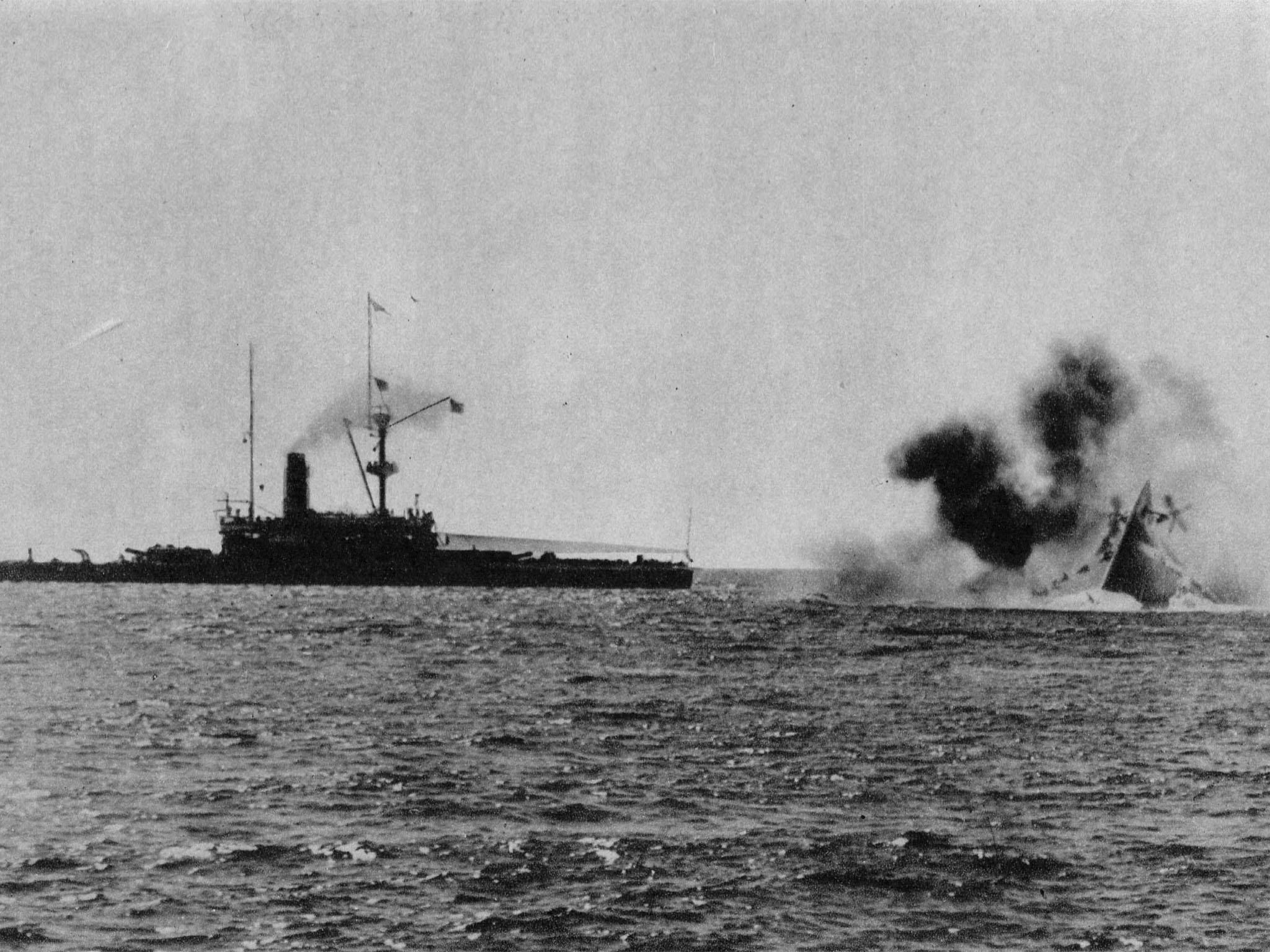

The toughened steel ram of the Camperdown tore 9 feet into the side of the Victoria, a full 12 feet below its waterline. After two minutes the two vessels disengage; but the Victoria lists, her many gun hatches and portholes taking in floods of swirling water.

Three minutes later, her bow dips – but an unrelenting Tryon demands any rescue boats return to their respective ships. Now he commands the leaking Victoria to head straight for the shores of Tripoli, five miles distant. After all, the Victoria’s engines are still running, many men below deck unharmed.

Maybe Tryon trusts that the “watertight” doors are still closed, so trapping many hands not already flushed into the ocean. Rapidly though, certainly by collision plus eight minutes, the whole of the Victoria’s bow is submerged, its stern far out of true, propellers turning in open air.

At last, but way too late, Tryon yells: “Abandon ship! Everyone for himself!” Five minutes on, the top deck goes under. Loosened boilers explode. Everything remotely portable bounces into the already hazardous surrounding ocean.

Two men on board refuse to jump ship: Reverend SD Morris, the chaplain on duty in the sick bay, who folds his arms across his chest, closes his eyes and says a final prayer; and Tryon himself, in time honoured tradition, going down on his watch, muttering: “this is entirely my doing, entirely my fault”.

Bourke – fitter and quicker than his superior – does, with great difficulty, make his escape. A distinguished fellow-escapee is the fevered John Jellicoe, one day himself to be promoted to commander-in-chief of the British Grand Fleet and dispatched to confront a detachment of the German navy off Jutland.

Staff Commander Thomas Hawkins-Smith, one of Tryon’s most vocal critics, also survives by clinging on to rigging.

In total, 358 of Victoria’s complement perished, coincidentally the same number as those believed to have been saved. Six bodies only were taken ashore, along with 173 men injured during the tumult. Jenkins on the Collingwood unarguably rescued more people than any other captain on duty – mainly due to his not recalling his lifeboats.

The stricken Camperdown, despite taking 90 minutes to effect partial water resistance, partial stability, somehow managed to keep going, battered, but without loss of life.

Back in England, reliable news was scarce. Only Markham’s telegram listing 22 surviving officers was to hand and so thousands of anxious friends and relatives milled round the Admiralty.

Anger and sorrow rapidly give way to philanthropy. Within three weeks, a remarkable distress fund of £50,000 was raised for Victoria widows and orphans – the equivalent of more than £5m today.

Debates raged about whether there should be a public inquiry into the disaster; some argued that would hand too many secrets of British seamanship to her enemies. A court martial was opened – Bourke’s second – with reporters allowed to witness some of the proceedings. Bourke requested that any captain sistering the Victoria was exempted as a judge.

In the dock, Bourke kept referring to navy ships as if they were on a highway, obeying “rules of the road”. But the very concept of obedience troubled the chief investigator, Sir Michael Culme-Seymour – “a safe pair of hands” – throughout his deliberations.

It appeared to be common ground that Markham on the Camperdown should have followed his first instinct and aborted the manoeuvre. But then, had there not been a collision, Markham would have been hauled over the coals for insubordination.Tryon actually gave his orders in person; ignoring them was extremely difficult, however foolish and foolhardy they were.

Culme-Seymour himself had to walk a tightrope: avoiding any hint at a precedent for altering (let alone ignoring) instructions from above. Tryon’s mental health was queried. Perhaps he was suffering from a brain disease, dementia, when he sent the Victoria to its doom?

In the end, Bourke came out best, his reputation undiminished. Markham, meanwhile, was censured almost as much as his flag captain, Charles Johnstone. Both could have acted differently at different stages in the unfolding catastrophe. Markham was stripped of his command, his pay halved, and relegated to minor duties. He died early, aged 65, in 1906.

Crucially, Tryon’s philosophy of seamanship was abandoned, history not permitted to be kind to his memory. Of the engaged fleet formation only a repaired Camperdown was still being tossed by high seas in 1898.

Like the Hollandia, the Victoria’s wreckage lay undiscovered for a long time. Not until 111 years and two months later, on 22 August 2004, was the ship found, by Austrian-Lebanese diver Christian Francis, assisted by British explorer Mark Ellyatt. It was positioned almost vertically, 140 metres below their search vessel. They concluded that a full 30 metres of the Victoria’s bow had buried itself in the seabed.

Three intriguing footnotes to the sinking of the Victoria continue to tantalise. First, it has long been the legend that, at the very moment of inevitable collision between the Victoria and the Camperdown, Mrs Tryon was hosting a party in her London mansion, when Commander Tryon himself, but ghostlike, descended the staircase to join festivities.

Second, one of Tryon’s hobbies was collecting memorabilia connected to his hero, Horatio Nelson. In 2012, Ellyat temporarily retrieved Nelson’s sword from Tryon’s cabin but, unsure what to do with this precious artefact, he hid the discovery in a different part of the wreck where it abides till this day.

Third, is the very title “Victoria” fated? After all, it was the MV Princess Victoria, a British Railways’ roll-on, roll-off ferry that sank on its passage from Larne to Stranraer, on 31 January 1953, costing 133 lives (at the start of the weekend of the great Lincolnshire floods, which left many people drowned across East Anglia and the Low Countries).

And barely six weeks after that terrible storm, a reordered SS Victoria also sank, this time striking rocks – just as the Hollandia did.

Why, though, recognise the anniversary of any ship’s demise when there are no living survivors and nothing to add to any inquest? Well, the lure of the sea still captivates and enchants even the most landlocked of the general population.

Despite all its dangers – because of all its dangers – the sea is where many of us are most alive.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies