Donald Trelford: Can it be right for Western reporters to endanger the lives of local colleagues?

The dilemmas arising from the armed rescue of the kidnapped New York Times reporter, Stephen Farrell, would keep a friend of mine, who runs the Institute for Global Ethics, supplied with enough material for several weeks of seminars. But for me, as an editor who once had a reporter executed in Baghdad, these issues are more than an academic exercise.

When Saddam Hussein hanged Farzad Bazoft on trumped-up spying charges, I was virtually accused of his murder by a rival paper, which said I was "culpably foolish" to send an Iranian to Iraq. In fact, he had been invited there by the Iraqi government, as he had been six times before – and I didn't even know he had gone. Even so, a sense of guilt remains after 19 years, and I can imagine the tormented self-analysis among Farrell's editors in New York after his Afghan interpreter was shot dead in the course of the rescue and left to lie where he fell. Corporal John Harrison of the Parachute Regiment, two civilians and dozens of Taliban fighters also lost their lives.

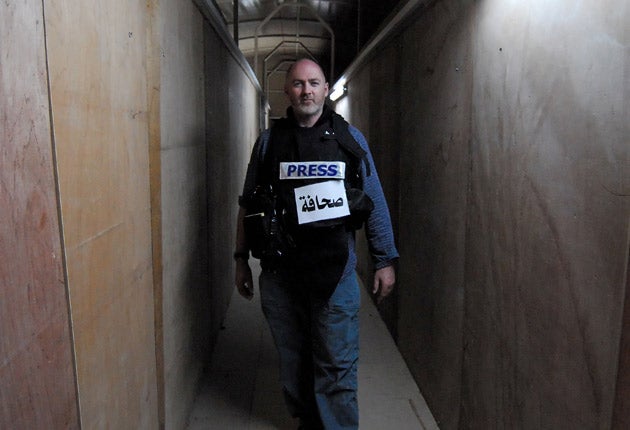

In the light of these deaths, a triumphal note in Gordon Brown's announcement of the raid rang especially hollow. It is still not clear to me whether saving the Afghan interpreter, Sultan Munadi, was ever part of the rescue party's mission. A commando evidently had a photograph of Farrell to help identify the British-born reporter – a difficult task, since he was dressed in Afghan robes and had grown a beard as disguise – but Munadi was immediately met by a hail of bullets when he stepped into the open and shouted "journalist". It seems likely that he was killed by British special forces.

His death highlights the important role played by locally employed people – as interpreters, drivers, security guards and domestic staff – in media coverage of both Iraq and Afghanistan. The New York Times has used over 200 in the past two years. The Afghan Independent Journalists' Association said local reporters often lacked the experience necessary to make split-second, life-saving judgments and should be given more training. Ann Leslie, the doyenne of British foreign correspondents, has always acknowledged the vital role played by these auxiliaries in the world's various war zones and urged that they be properly protected and their families looked after. In Vietnam, two Observer correspondents ended up adopting children from the families of their interpreters and brought them to the west.

Leslie describes some correspondents she has met as "war junkies" who are addicted to danger. I don't know Mr Farrell, who edits a blog called The New York Times at War, so I can't say whether he falls into this category or not. He has been kidnapped before, when he was Middle East correspondent for the London Times, and has been nicknamed "Robohack" by some of his colleagues. This would be no concern of ours, unless it suggests that he may be the type to take one too many risks for a story and thereby put his companions in danger. He seemed to admit something of this sort when he said they had stayed too long in an Afghan village, investigating the death of over 100 civilians when a Nato strike force blew up two petrol tankers hijacked by the Taliban. He is said to have ignored warnings from the Afghan police not to go into the area.

If so, can it be right for reporters to endanger the lives of their local colleagues in this way? Is it the job of soldiers to save the lives of journalists who may have taken too many risks? And should politicians order troops into battle to save them? In this case, what evidence was there that the lives of Farrell and Munadi were in such immediate danger that the assault took place even while hostage negotiations were still going on? Their captors had allowed them to use their mobile phones and were discussing a ransom when the rescue force arrived.

There are few reliable guidelines for reporters in this treacherous area. Anthony Loyd, a war correspondent on The Times, has suggested a few: be afraid; be in secure shelter by nightfall; do not take staff from one ethnic background into alien territory; get out the moment you hear the Taliban are near – "if you know of their presence, they will already know of yours." And finally, "never leave your dead on the battlefield." The editors of the New York Times may be applying these tests to Mr Farrell.

The spying game

One sentence made me sit up in Harold Evans's sprightly new memoir, My Paper Chase: "No journalist should ever, ever agree to act for an intelligence agency, whatever the invocation, whatever the desire to be patriotic." I couldn't help thinking of the 88 foreign correspondents hired by Ian Fleming for Mercury News Network, the agency that supplied titles, most notably Sir Harold's former paper, the Sunday Times, after the war.

Fleming was fresh from his service as assistant to the director of Naval Intelligence. Why did they need 88 foreign correspondents when the Sunday Times had only eight pages and few of these carried foreign news? A number of Fleming's appointments clearly had (shall we say?) experience of the secret world, but then so did staff on a number of other papers in post-war Fleet Street.

The Observer was no exception. Its long-serving editor David Astor had served in the Special Operations Executive during the war and brought some colleagues with him. Terry Kilmartin had saved Astor's life by applying a field dressing when he was wounded on being dropped into occupied France: his reward was to become literary editor.

Once, while I was lunching in the Garrick Club, a stout figure padded over to my table and asked: "Any news of Gavin?" – apparently a reference to The Observer's star foreign correspondent. "Do you mean Gavin Young?" I said. "The last I heard he was in the Far East. He often goes weeks without telling us what he's up to, then he files a marvellous piece."

"We heard," said Sir Maurice Oldfield, head of MI6 (for it was he), "that he had been swept overboard in a storm off Celebes. If you get any news, you'll know where to find me." When I got back to the office, I discovered that Gavin had survived the shipwreck. I was able to pass on the good news to the man who, I could only assume, was Gavin's joint employer.

Stand up and fight

"Stand up for The Observer" is the journalists' battle cry as they fight to save their 218-year-old paper from feared closure by the Guardian Media Group. A public meeting at the Quaker Meeting House in London's Euston Road next Monday will be chaired by the comedian and columnist David Mitchell. A number of celebrities will be there to support the world's oldest Sunday paper. Anyone who cares about the future of quality journalism is welcome. I shall certainly be there.

Have a ball

An unlikely alliance of Alastair Campbell and Piers Morgan is promoting this year's Press Ball, to be held on 15 October in aid of the Journalists' Charity. The London Press Club is organising a piss-up in a brewery – the Brewery in Chiswell Street, to be precise, close to the Barbican. Tickets and tables at www.thepressball.com.

Donald Trelford was editor of The Observer from 1975 to 1993, and is Emeritus Professor of Journalism Studies at Sheffield University

donaldtrelford@yahoo.co.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks