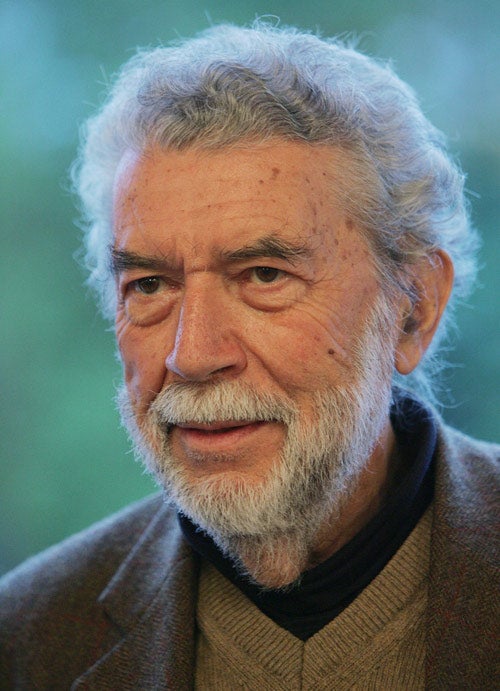

Alain Robbe-Grillet: Leading 'new novelist' and film-maker who through his work sought to undo the conventions of fiction

The creation of the nouveau roman, or "new novel", in the 1950s was the intellectual event in France of those years. The five or six writers who helped in it were never a school, but they thought alike in wanting to do away with the wearier conventions of the realist novel. Out went the familiar comforts of a logical plot and distinctive, "believable" characters.

Many novel-readers were not at all taken with this ascetic programme and they were taken least of all with the brash pronouncements of the most hard-boiled of all the new novelists, Alain Robbe-Grillet. He had come to literature, unusually, from mathematics and the hard sciences; and rather than perpetuate it, his declared intention was at long last to bury it.

Robbet-Grillet came to be known in France as the "pope of the new novel". It was a title that he adored – and loved to play with. When he was elected to the Académie française in March 2005, he asked to be excused the green uniform, cocked-hat and ceremonial sword. Clergymen were excused, he pointed out, and he was the "pape du nouveau roman".

In the event, Robbe-Grillet never turned up at the Académie to give the traditional eulogy to his predecessor. He was therefore never fully installed as a member. His death, following a heart attack, brings to 10 the number of academicians who have died in the last 18 months.

Robbe-Grillet, born in 1922, was brought up first in Brest and then in Paris. His degree was in agronomy. He did forced labour for a time during the German occupation of France and after the Second World War worked in various laboratories and agronomic institutes.

He published a first, decidedly opaque novel, Les Gommes, in 1953 (translated in 1966 as The Erasers), which hardly anyone understood for what it was. It reads like a wilfully contradictory detective-story, full of teasing echoes of the Oedipus myth. Its true subject, though, is the attempted "murder" of reality by the over-excited imagination of the writer, who insists on forcing an order of his own on the world rather than admit it is, in truth, alien to him. This was to remain Robbe-Grillet's harsh, anti-humanist philosophy: in a scientific age, fiction is an aberration and a weakness; it can only lose out ultimately to facts.

The novels by which he became successful and widely read were those that came later in the 1950s – Le Voyeur (1955; The Voyeur, 1958), La Jalousie (1957; Jealousy, 1960), Dans le labyrinthe (1959; In the Labyrinth, 1967). These too dramatise the fevered, illegitimate workings of the writer's imagination, as it tries repeatedly, and fails, to call reality to some final order. By 1960 Robbe-Grillet was established as the most radical and commercial of the new novelists.

It became apparent more slowly that he was also the most humorous, as the novels that he wrote grew more sardonic and extreme, until they were lurid parodies of how the imagination works, rather than merely emphatic examples of it. He now turned to writing films, first and most famously the screenplay of L'Année Dernière à Marienbad (Last Year in Marienbad, 1961), which was directed by Alain Resnais. Resnais shrank from taking all the huge liberties with time and sequence that Robbe-Grillet asked for, and the frustrated novelist, ever the purist, decided that in future he would do his own directing.

He made a number of films, all of them on the same principles as his novels, exploiting what he took to be the stock – ie sado-erotic – ingredients of the contemporary (male) imagination. But cinema audiences need their realism, and Robbe-Grillet's witty ways of withholding it from them meant that his films were mainly shown in the art-houses. They came under fire, too, from feminists and others, for being pornographic.

This last was a charge Robbe-Grillet defended himself against in a more or less autobiographical trilogy: Le Miroir qui revient (1984; Ghosts in the Mirror, 1988); Angélique ou l'enchantement ("Angelique or The Enchantment", 1987) and Les Derniers jours de Corinthe ("The Last Days of Corinthe", 1994). There he restates, more moderately this time, his youthful grievances about realism in fiction and the cinema, but concedes that the imagination has its virtues, that it is not going to wither away in favour of science. Indeed he now claimed that fantasising in novels or in films is good, if it stops us acting out our fantasies in life itself.

In this point of view he was influenced in later years by his wife, Catherine Rstakian, a celebrated writer and apologist for sado-masochist fantasies under the pen-name Jean de Berg or Jeanne de Berg. A former actress, she is also one of the most sought-after organisers in Europe of sado-masochistic soirées for the literary classes. They married in 1957. By the end of his life, Robbe-Grillet was openly in favour of literature and was even teaching it himself, at universities in the United States.

Robbe-Grillet's career was built on a sly and amusing paradox: of using fiction over and over again to undo the conventions of fiction. But how cleverly and engagingly he did it.

John Sturrock

Alain Robbe-Grillet, novelist and film-maker: born Brest, France 18 August 1922; married 1957 Catherine Rstakian; died Caen, France 18 February 2008.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies