Corin Redgrave: Actor whose involvement in radical politics kept him away from stage and screen for two decades

With his genetic inheritance – his father was one of the stage greats of his era, Sir Michael Redgrave, and his mother, Rachel Kempson, was a distinguished actress – it was hardly surprising that Corin Redgrave, like his sisters Vanessa and Lynn, should choose a career in the theatre. After an early period of promise which included some performances for the Royal Shakespeare Company marking him out as a significant talent, his involvement with radical politics (often in alliance with his elder sister Vanessa) took him away from the theatre for two decades. His return in the 1990s was an extraordinary comeback, seeing him ceaselessly active as director (opening a new theatre venture, the Garrick at Lichfield, in 2003), theatrical campaigner (lobbying against the proposed demolition of the Arts Theatre in London), writer and actor on stage and screen. Intriguingly, some of his later stage successes were in roles associated with his father, including Crocker-Harris in The Browning Version, Frank Elgin in The Country Girl and King Lear for the RSC.

Born just before the outbreak of the Second World War in London, he was christened Corin William (Corin after the character in As You Like It, in which his father had scored an early success opposite Edith Evans). His strong-willed and strong-voiced paternal grandmother vetoed William Corin, insisting that future schoolmates would mock the "W.C." initials. He spent most of his early years in the idyllic surroundings of Bromyard, near Worcester, in a house hideous from the outside but comfortable and rambling within which belonged to his mother's cousin Lucy Wedgwood.

Far from London's bombs he and Vanessa (and Lynn from 1942) had a childhood of books, abundant eggs and cream and games; theatre was a passion, with self-penned, -acted and -directed playlets performed in the house or on garden terraces, with hand-written programmes and, inside, rows of light-bulbs as footlights. With their parents often in London or on tour, or in their father's case on location and in film studios after his naval service, the children saw little of them until after the war and the family's move to one of London's most beautiful houses, on the Thames at Chiswick.

Redgrave's first school – a Malvern establishment run by a headmaster both supercilious and uncaring – was a miserable experience and he moved to Westminster, where he excelled both academically and in school plays (his Portia in The Merchant of Venice was something of a Westminster legend and he was allowed to play Dunois' Page in Saint Joan at the Embassy Theatre when his mother played the title role). He was a golden boy at Cambridge, also; he chose King's, where Dadie Rylands (who had directed Michael Redgrave for the Marlowe Society in the 1920s) still kept an avuncular eye on young theatrical talent. Part of an especially strong theatrical generation of undergraduates – Ian McKellen, Derek Jacobi and Clive Swift among them – Redgrave dazzled in revue and classics alike while collecting a First in English.

Nepotism helped him get his first break – Kempson had been a member of the first English Stage Company of 1956 at the Royal Court – when he went to Sloane Square as assistant to the director Tony Richardson in 1962. Nepotism rarely secures subsequent jobs however, and Redgrave had to audition before Richardson cast him as Lysander in a highly physical A Midsummer Night's Dream (Royal Court, 1962) which the press panned despite a talented young cast including his sister Lynn, also making her professional début. Also at the Court he played a Sebastian of romantic yearning in an adventurous Twelfth Night (1962) and made a considerable impact as the Pilot Officer in Arnold Wesker's Chips With Everything (Royal Court and Vaudeville, 1962), in which he also made his Broadway debut.

By now married to a bright, extrovert 1960s charmer, Deirdre Hamilton-Hill, Redgrave was establishing himself; he revealed an unexpectedly astute drollery as an exquisitely tailored Cecil Graham, a dandy resembling an etiolated Spy cartoon, in a revival of Wilde's Lady Windermere's Fan (Phoenix, 1966). Redgrave and Ciaran Madden, like their predecessors Keith Michell and Diana Rigg, made the plodding Abelard and Heloise (Wyndham's, 1972) – noteworthy mostly for a brief and murkily lit nude scene – seem decidedly better than it was on taking over the title roles.

A leap forward in critical and public estimation came with Redgrave's outstanding RSC performance as Octavius Caesar in Julius Caesar and Antony and Cleopatra (Stratford, 1972, Aldwych, 1973). Particularly with the greater exposure in the latter, opposite Janet Suzman and Richard Johnson in the title roles in Trevor Nunn's production, Redgrave revealed a chilly blond Roman arrogance which immediately distanced him from the perfumed voluptuousness of Egypt, gradually exposing a master of the intricate tactics of realpolitik. Coinciding with a few noteworthy film roles, beginning with the son-in-law of Paul Scofield's Thomas More in Fred Zinnemann's A Man for All Seasons (1966), and including his perkily optimistic Brother Bertie, cheerfully riding off to the front on the pier-fairground train of Oh! What a Lovely War (1969), Redgrave's career seemed set fair to bloom.

It was at this stage that his political involvement, growing from CND days, began to take over, and his marriage collapsed in 1975 partly due to that pressure. Redgrave did not consciously abandon acting but as he veered to what much of the theatrical establishment regarded as extremist policies (not least over his challenges to many of the policy decisions taken by the actors' trade union Equity) it is undeniable that avenues became closed to him (he always believed that the BBC in effect blacklisted him).

With his burning conviction in the ideals of the Trotskyite Workers' Revolutionary Party, in which he and Vanessa were the most prominent figures, in the later 1970s he moved to Yorkshire, where the party's headquarters and study centres were based. Many old colleagues saw only a self-blinded fanatic; his father, who had shrunk from left-wing involvement after a wartime episode over his involvement with the People's Convention (Communist-backed, as it transpired) which saw him blacklisted by the BBC, never criticised him, even if he did not always fully comprehend his son's logic, and nor did his mother. The knee-jerk recoil of many in his profession (and often, too, in a hostile press) overlooked or misunderstood the reasoning which underpinned his compulsion to battle for what he saw as a more just society. As with his father, a deep shyness could on occasion lead to an impression of gelid aloofness, but Redgrave was a genuinely courteous, caring man of passionate convictions.

Following a rancorous split in the WRP and after a happy second marriage to Kika Markham – daughter of an old colleague of his father's, David Markham, whose socialist beliefs influenced both Michael and Corin – Redgrave's astonishing professional renaissance began. Some said he became a much-improved actor only after his father's death (in 1985); performances such as his Octavius somewhat refute the argument, but a certain coldness and physical constraint seemed to loosen and thaw. He never abjured politics, although he and Vanessa came to believe that human rights was the greatest issue, founding in 2004 the Peace and Progress Party.

In his father's 1950s success (then titled Winter Journey) of Clifford Odets' The Country Girl (Greenwich, 1995) he took on the hugely challenging part of Frank Elgin, the alcoholic has-been star trying for a Broadway comeback. The production was sadly muffled, but he still found a moving pathos in this wreck of a man with a spark of genius still fitfully flickering.

A welcome return to the RSC in The General from America (Stratford, 1996) saw Redgrave in a somewhat underwritten role as George Washington, while his first National Theatre experience was in a below-par Marat/Sade (National, 1997).

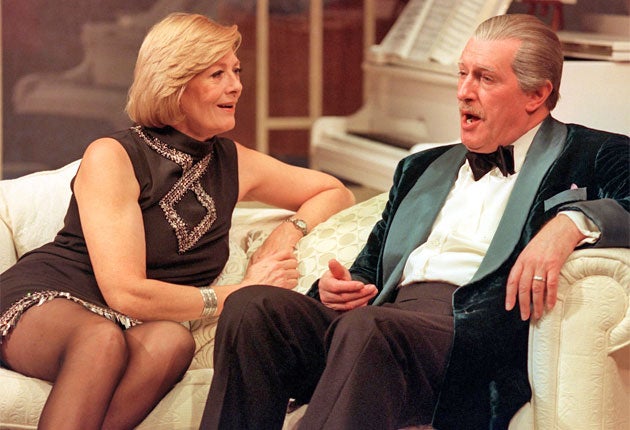

Back in the commercial theatre with Noël Coward's A Song at Twilight (King's Head and Gielgud, 1998) Redgrave joined his wife (playing his wife) and sister Vanessa (as his ex-mistress) to play the famous old writer Hugo Latymer fighting off blackmail and exposure in his Swiss hotel suite. More than a few press pieces seized on the piquancies of Redgrave's appearance in a play structured round a character with a secret bisexual life (pace Redgrave père) written by Coward, for a time their father's lover. But the play was inspired more by Max Beerbohm or Somerset Maugham and Redgrave's performance, face and voice suggesting fathoms of banked emotions was the revelation of the evening.

The best was yet to come. The National Theatre's premiere of an early Tennessee Williams piece, Not About Nightingales (1998) was a shattering prison drama with a performance of impressive, sweaty menace from Redgrave. He and Vanessa made a wonderful brother-and-sister act as Ranevskya and Gayev in Trevor Nunn's The Cherry Orchard (National, 2000). His Gayev was an innocent child with a kernel of selfishness, a performance packed with finely observed detail. Also at the National he played Oscar Wilde with a movingly weary sense of waste in De Profundis (2000) and made up another triumphant pairing, with John Wood, in Harold Pinter's No Man's Land (2001).

Redgrave had been ill with prostate cancer but recovered to play King Lear at the RSC. The production opened with panache: a huge table surrounded by the spotlit faces of an expectant court, be tricked when a seemingly doddery ancient staggered on then flung away his stick roaring with laughter, a dangerously wilful monarch. But it faltered when approaching the empyrean of real tragedy. Redgrave's performance was sporadically brilliant with some stunning new-minted line-readings, but on too few occasions did it stab the heart.

Happier was his tour de force as the critic Kenneth Tynan (once his father's bugbear) in Tynan (Stratford, 2004, and Arts, 2005); he never moved from his chair and made no great effort at impersonation, but the evocation of Tynan's aphoristic talent was funny and affecting. Tynan was as engrossing as his own solo play Blunt Speaking (Chichester, 2002) centred round his father's old Cambridge friend Anthony Blunt and his exposure as a traitor. In that, as in so many of his later performances – including a heart-wrenching portrayal of Crocker-Harris, the repressed schoolmaster of Terence Rattigan's The Browning Version at Derby Playhouse in 1997 – Redgrave demonstrated his talent for playing riven men, often with double lives.

His theatrical rebirth was paralleled on screen. Later films rarely gave him major roles, but he had an aristocratic aplomb as Andie McDowell's husband in Four Weddings and a Funeral (1994) and had several strong scenes in Enigma (2001). Redgrave had tackled little television earlier in his career, although he gave a splendid performance of apparently spontaneous charm cloaking the predatory core of Steerforth in David Copperfield (1969). Later he appeared in many series – several of Lynda La Plante's Trial and Retribution included – and was extremely fine as the wispy Sir Walter Elliot in Persuasion (1995). But his finest work on the smaller screen was in the re-make of The Forsyte Saga (2002) as the elder Jolyon. He suffered a heart attack in 2005, but continued to do good radio work, and last year appeared in Trumbo, about the blacklisted screenwriter Dalton Trumbo, at the Jermyn Street Theatre.

Corin Redgrave should have written more. He was a talented writer and for radio, in addition to the original Blunt Speaking, he wrote Roy and Daisy, a delightful programme based on the stormy relationship between his paternal grandparents, touring players both. His memoir, My Father, Michael Redgrave (1995), was beautifully written, a beguiling evocation of childhood, and although not a formal biography it gave a portrait of his complex father so compassionate and understanding as to belie his claim that "biography is a kind of revenge".

Alan Strachan

Corin William Redgrave, actor, director, writer and campaigner: born London 16 July 1939; married 1962 Deirdre Hamilton-Hill (marriage dissolved 1981; died 1997; one son, one daughter;), 1985 Kika Markham (two sons); died London 6 April 2010.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies