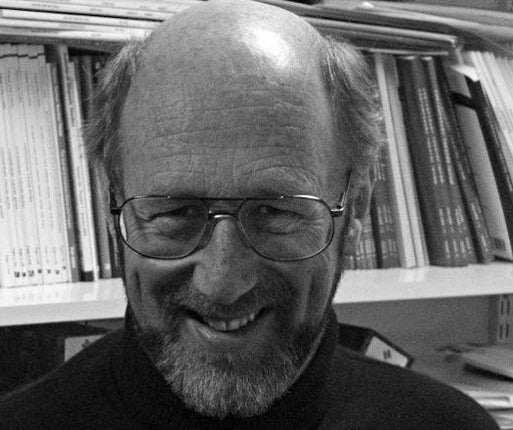

David Bradby: Theatre scholar whose passion for French drama inspired a host of seminal books

"In the UK," said someone at a 1999 academic conference, "David Bradby is French theatre." Fair comment about a man who wrote a dozen seminal books on European theatre, was a passionate teacher of French drama at three British universities, and directed, translated, and advised on works by playwrights from Adamov to Vinaver. But Bradby's scholarship and enthusiasm ran wider: Russian drama, contemporary British theatre, ancient Japanese drama (he was enormously supportive of the establishment of a Noh stage and centre at Royal Holloway, University of London), the theatre of Peter Stein in Berlin and the plays of Vaclav Havel in Czechoslovakia. For him, research and theatrical performance were deeply connected.

Bradby was born in Colombo, in what was then Ceylon, the son of the last European principal of Royal College. At Rugby School he developed a passion for directing plays, taking over the production of light comedy from his English master, and in his first year at Trinity College, Oxford – where he read modern languages – directing Chekhov's The Seagull in the college gardens. Bradby had got hold of David Magarshack's newly published translation of Stanislavsky's promptbook for the original Moscow Arts Theatre production and this crystalised both his love of theatre and his concern for the details of directing.

While still at Oxford, he put on the British premiere of Arthur Adamov's Professor Taranne, starring the future Monty Python member Terry Jones. The Theatre of the Absurd became a lifelong love of Bradby's and two of his books in particular, Modern French Drama 1940-80 (1984), and the brilliant critique Beckett: Waiting for Godot (2001), celebrated this enthusiasm.

After Oxford, Bradby trained as a teacher. By then he had married the journalist and novelist Rachel Anderson, who had been wardrobe mistress on his student production of Gogol's The Government Inspector, and by then, also, he'd decided that his future lay in education rather than theatre. The "conversion" had happened in Paris, where he worked with the great French director Roger Planchon. If he couldn't be as good as Planchon – and he saw that he couldn't – he'd turn to his other talent.

Luckily for scholarship and for drama, his love of theatre persisted and in 1966 he wrote a doctoral thesis on Adamov at Glasgow University, as well as teaching in the French department. By 1970 he'd crossed the corridor from French to theatre studies at the University of Kent, founding a new department of drama. Here there was plenty of scope for directing Beckett and Havel and introducing British audiences to the plays of Michel Vinaver, who came over in person to advise Bradby on the world premiere of his Portrait of a Woman. He also taught overseas at the University of Ibadan in Nigeria – where political riots prevented the opening of his production of Jean Genet's The Blacks – and Caen, where he was made head of the drama department.

In 1988 Bradby became professor of theatre at Royal Holloway, where he stayed until his retirement in 2007. His pupils there remember him as an inspired and playful teacher, turning lectures into theatrical adventures; his colleagues, as a man of integrity, hugely preferring the politics of life to those of academia. And though he chaired and sat on numerous committees, he never let administrative duties interfere with his intellectual creativity: his books included Directors' Theatre (with David Williams, 1988), The Theatre of Michel Vinaver (1993), and Mise en Scène: French Theatre Now (with Annie Sparks, 1997).

His co-editing, with Maria Delgado, in 2002, of a book of essays on the geographical and cultural importance of Paris as a crucible of theatre, The Paris Jigsaw: Internationalism and the City's Stages, was a typically penetrating and eclectic achievement. As always, Bradby was in touch with live theatre: he directed the first British production of Luigi Pirandello's The Mountain Giants, beating the National Theatre to it, and worked with the Royal Court, the Gate, Max Stafford-Clark's Joint Stock Company, and above all, with Sam Walters at the Orange Tree, Richmond, whose 1980s Vinaver productions he advised on. It was in the interval of Walters's production of the British premiere of Vinaver's Overboard in 1997 that David Bradby was made a Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres by the French Ambassador; there was slight disappointment, perhaps, that he missed getting a kiss from Jeanne Moreau, who did the honours the next day.

Long-term commitments particularly close to his heart were the editorship of Studies in Modern Drama, and the co-editorship of Contemporary Theatre Review. His last public appearance was in May 2010, when he was presented with a festschrift in his honour.

When Bradby came into a room – lean and bearded, his eyes alight with curiosity and mischief – everyone's spirits lifted. His children have a vivid memory of being taken to the Cartoucherie outside Paris, when two of them were still of primary-school age, to watch a three-hour performance in French of one of Ariane Mnouchkine's epics. Bradby expected them to be puzzled and enchanted, and they were. A quiet Christianity ran through this enlivening man, as did love of music, wine and trees. It seems fitting that after his Norfolk funeral, family and friends should walk back from the church to his house on the edge of a wood, singing gospel songs, folk music and carols.

Piers Plowright

David Bradby, theatre scholar: born Colombo, Ceylon 27 February 1942; married 1965 Rachel Anderson (one daughter, three sons); died Northrepps, Norfolk 17 January 2011.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments