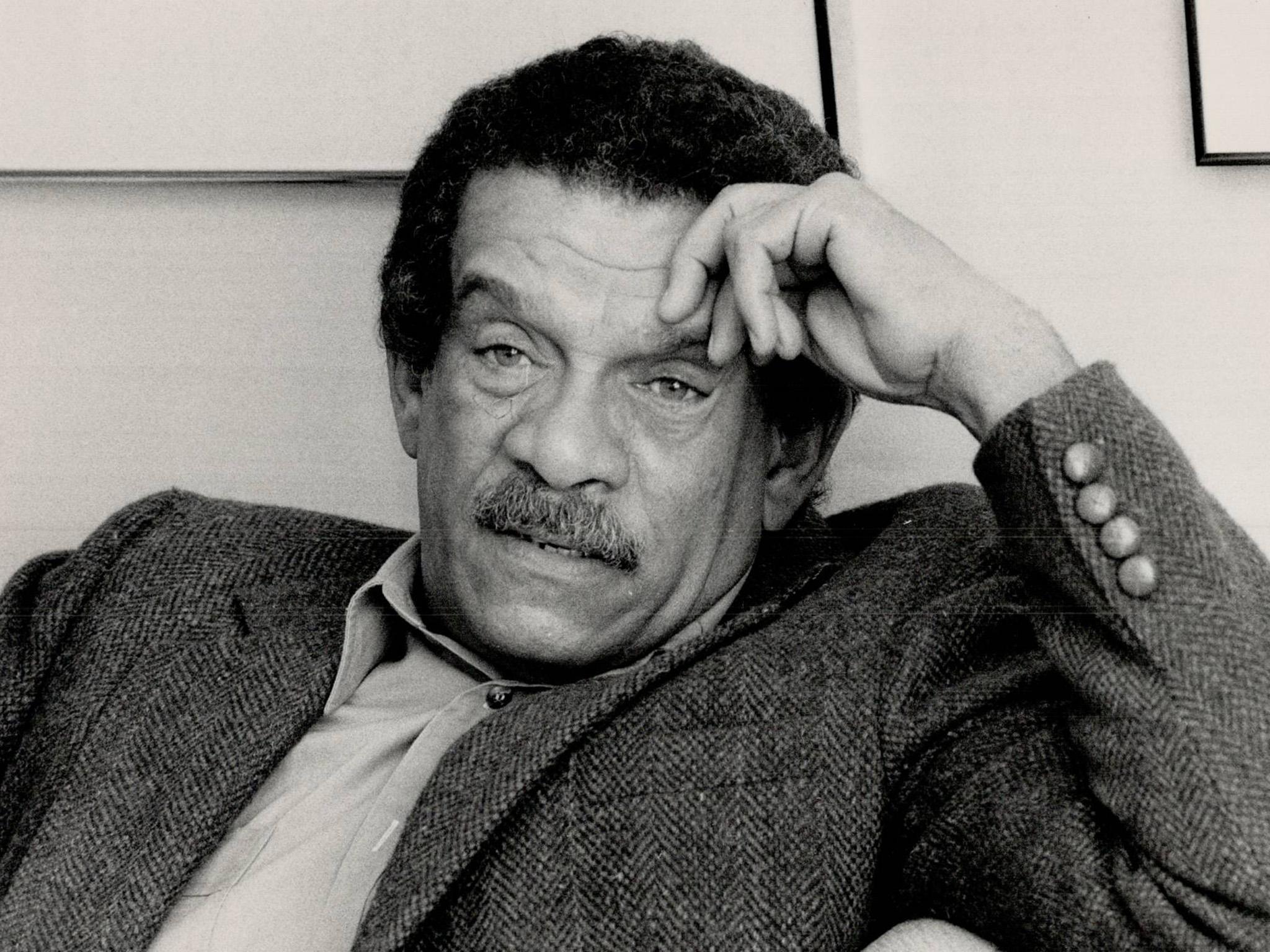

Derek Walcott obituary: St Lucian Nobel Laureate and poet remembered

His life-long task as a poet was the naming and the dignifying of the specifics of the island of his birth – its fauna, its people, its sea – in the language of his education

The Nobel Prize-winning poet Derek Walcott was born in 1930 on the tiny island of St Lucia in the Eastern Caribbean. In those days, it was a somnolent outpost of the British Empire with a complicated history – it had changed hands between the French and the English no fewer than thirteen times. And before those multiple occupations, there was the dark and largely unwritten history of slavery. The language of the schoolroom was English, the languages of the street French and English Creole.

Walcott, who had an English grandfather, grew up as an English colonial child, with a passion for the English language, and for a literature which was full of the names of things he could imagine and read about but not see – the oak tree, for example. His life-long task as a poet was the naming and the dignifying of the specifics of the island of his birth – its fauna, its people, its sea – in the language of his education. He was a poet who stressed above all the importance of the local.

In interviews and poems, Walcott repeatedly used to refer back to a statement once made in a book written by the English historian Anthony James Froude in 1888. Referring to the Caribbean and its history, Froude wrote: “There are no people there in the true sense of the word, with a character and purpose of their own.” Stung and challenged by this insult, Walcott’s entire endeavour as a poet was to demonstrate through his own writing that Froude was talking nonsense.

This is not to suggest that Walcott wrote out of some deeply rooted animus against the coloniser and his language. English was the language of his imaginative life, and some of his favourite poets were as rootedly English as you could ever imagine – Thomas Hardy and Philip Larkin, for example. His native patois, French Creole, played a part in his work too, but its influence was felt more profoundly in the exuberance of his writing. He always inhabited the present with tremendous gusto. His words felt driven by a tremendous rhetorical push. He was never a quiet poet, never an ironist who sat in the corner of the room and spoke out of the side of his mouth. He delighted in the craft of writing – every page bears witness to this fact. What is more, his poetry is one which has absorbed the work of other writers, English or American, like a thirsty sponge – you hear their ghostly echoes everywhere in his work, from Shakespeare, to Walt Whitman, to Robert Lowell.

Walcott spent much of his professional life in America – he taught for twenty years at the University of Boston. He once defended this decision with his characteristic robustness. America recognised his talents and gave him a good living, something which could not have happened had he remained in the Caribbean.

Walcott always had his detractors. Should he not have written his work in the Nation Language of his Caribbean contemporary Edward Kamau Brathwaite? Was not his use of English and its traditional verse forms – Walcott seldom wrote in free verse – some kind of betrayal? Walcott had two answers to these critics. One was that phoneticised French Creole was too narrow and primitive a language to encompass the breadths of his ambitions as a poet. Dialect and patois may fertilise and even animate a poem, but they are not everything. By way of vindication he pointed to the example of James Joyce. “Who is more Irish than Joyce?” he once remarked. And yet Joyce “was beyond the local quarrel of writing in the Irish language”. The second argument was perhaps the more telling: those who dictated to him in what language he should write were driven by political prejudice and not literary need. “I don’t think there is any such thing as a black writer or a white writer,” Walcott once wrote with scorn. “Ultimately, there is someone whom one reads.”

His masterpiece was undoubtedly the epic-length poem “Omeros”, which he published in 1990. Its title, and the characters in the poem, loosely refer to Homer and some of the heroes of his epic poems. But Walcott gifted the names to local people – Achille and Philoctete are simple island fishermen. They too can be dignified by the attentions of a writer, that decision seems to be pointing out to us. And anyway, wasn’t Homer himself writing about a relatively small-scale civilisation of multiple islands? The heroes of the poem are as much its flora and fauna, and especially the sea-swift which, in an extraordinary section of sheer phantasmagoria, drags Achille back to Africa in his fragile pirogue to confront the ghostly emanation of his father. Walcott’s description of the flight of the sea-swift had such lightness, lift and life – the bird positively skimmed across the ocean. The whole enterprise felt and sounded like a hymn of praise to the sheer bountifulness of the earth, with Walcott feasting on the English language like a glutton.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies