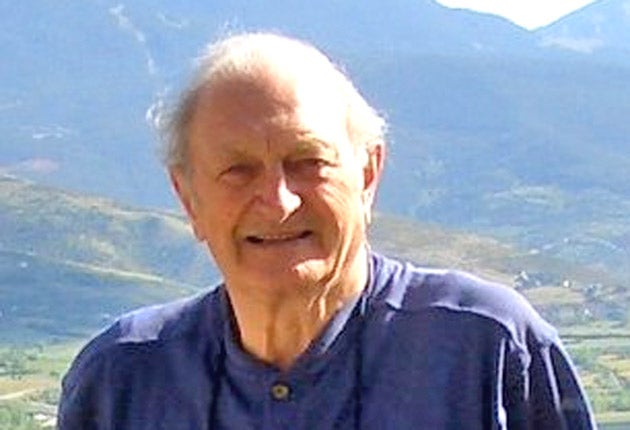

Doctor John Henderson: Psychiatrist who championed the rights of the mentally ill across Europe

Doctor John Hope Henderson was a charismatic psychiatrist who became a champion for the human rights of the mentally ill and for the promotion of mental health across Europe.

Born in the Borders of Scotland, he graduated in medicine from the University of Aberdeen in 1954. He became a keen mountaineer and rugby player, captaining the Aberdeen Academicals. He served in the Royal Army Medical Corps on National Service in Kenya. On his return, he trained in psychiatry under the renowned teacher Professor Malcolm Miller, becoming a consultant psychiatrist at Bilbohall Hospital in Elgin aged 33.

At Bilbohall, Dr Henderson was Physician Superintendent. With his characteristic enthusiasm, he set about modernising the local community and hospital services, attracting the then Prime Minister, Edward Heath to open the new facilities. Henderson travelled to professional meetings all over Scotland, leaving home early to drive 150 miles to central Scotland, before the days of dual-carriageways. He was hungry for new knowledge, learning and support to modernise mental health services across Scotland.

In 1969 he was appointed to a larger mental hospital, in Broxburn. There he initiated the development of community and primary care services for West Lothian, which led later to the closure of the old Victorian asylum buildings. Soon he was sought to be Principal Medical Officer at the Scottish Home and Health Department, with responsibility for advising government ministers on mental-health policy. While there, his advice and clinical leadership were highly valued, especially in challenging times such as during the high-profile murders of staff at the Carstairs state mental hospital.

In 1976 he was appointed as an advisor in mental health to the World Health Organisation, first for the South-east Asia region based in New Delhi, and then for Europe, based in Copenhagen. He was recognised by WHO to have served with distinction, contributing to the development of many national and regional mental-health modernising programmes.

It was a challenging life, not only for Henderson, but for his family. His wife, Toshie, who was born in India, helped them to keep in touch with their family and many friends, writing fascinating epistles about their activities, but their sons remained in Scotland for their education. Some stories became legend, such as the toughness required to remain sober when exposed to hospitality on the remote plains of Outer Mongolia.

In 1985 he came back to the UK as medical director of the large independent mental hospital, St Andrews at Northampton, where he remained until 1993. His retirement from employment was the start of over 15 years of continuous philanthropic endeavour. It was this that resulted in Henderson becoming known and respected all over Europe for his work supporting the human rights of people living with mental illness; and in his championing of the issue on the European political stage. He returned to Scotland, living at Haddington, but his home-from-home was Brussels, as well as other European cities.

Henderson was first active in the World Federation for Mental Health, being president of the European Region Council from 1994-97. He was a founder-member and policy adviser to Mental Health Europe, now the largest and most influential non-governmental mental-health organisation in Europe. He became involved in the reform of psychiatric services, particularly in Eastern Europe. Here he learned to combine his policy skills, natural diplomacy and generous spirit with his strong beliefs in justice and equality.

In Greece he led an international team established in the 1990s by the EU to oversee de-institutionalisation and psychiatric reform. This was required following the 1980s scandals highlighted in the plight of psychiatric hospital residents incarcerated on the island of Leros.

In 2005, he had a major role at the WHO Europe Ministerial Conference for Mental Health. He was a keynote speaker, and was later much involved in helping develop a European-wide mental-health strategy for the European Commission. Unfortunately this strategy was not accepted by member states. His disappointment, aged nearly 80, was to say that he would just have to start the work again.

In addition to his work life, Henderson had a rich family life. He and his wife have four sons, two of whom work in mental health, and 10 grandchildren. Their highlights were large family gatherings. The last was held in Braemar to celebrate his 80th birthday, two months after his terminal cancer was diagnosed. Naturally it was emotional for him, and he was uncharacteristically reluctant to come down for dinner one evening, but his wife Toshie said: "You may be dying, but you'll not die tonight, so put on your kilt and join us." He joined the family, taking his place at the table with his usual humour and character.

Henderson was always an active person who had many warm friendships. Holidays were highlights, such as when skiing and walking from their chalet in the Pyrenees. He was an accomplished cook, knowledgeable about food and wines. Meeting with friends and sharing a meal together was always enjoyable. His sense of humanity and energy for what he believed in will be sorely missed, as will his campaigning zeal behind one of his favourite phrases: "There is no health without mental health."

Cairns Aitken

John Hope Henderson, psychiatrist and mental-health activist: born Galashiels, Selkirkshire 2 November 1929; married 1959 Margaret 'Toshie' Anne King (four sons); died Haddington, East Lothian 4 January 2010.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies