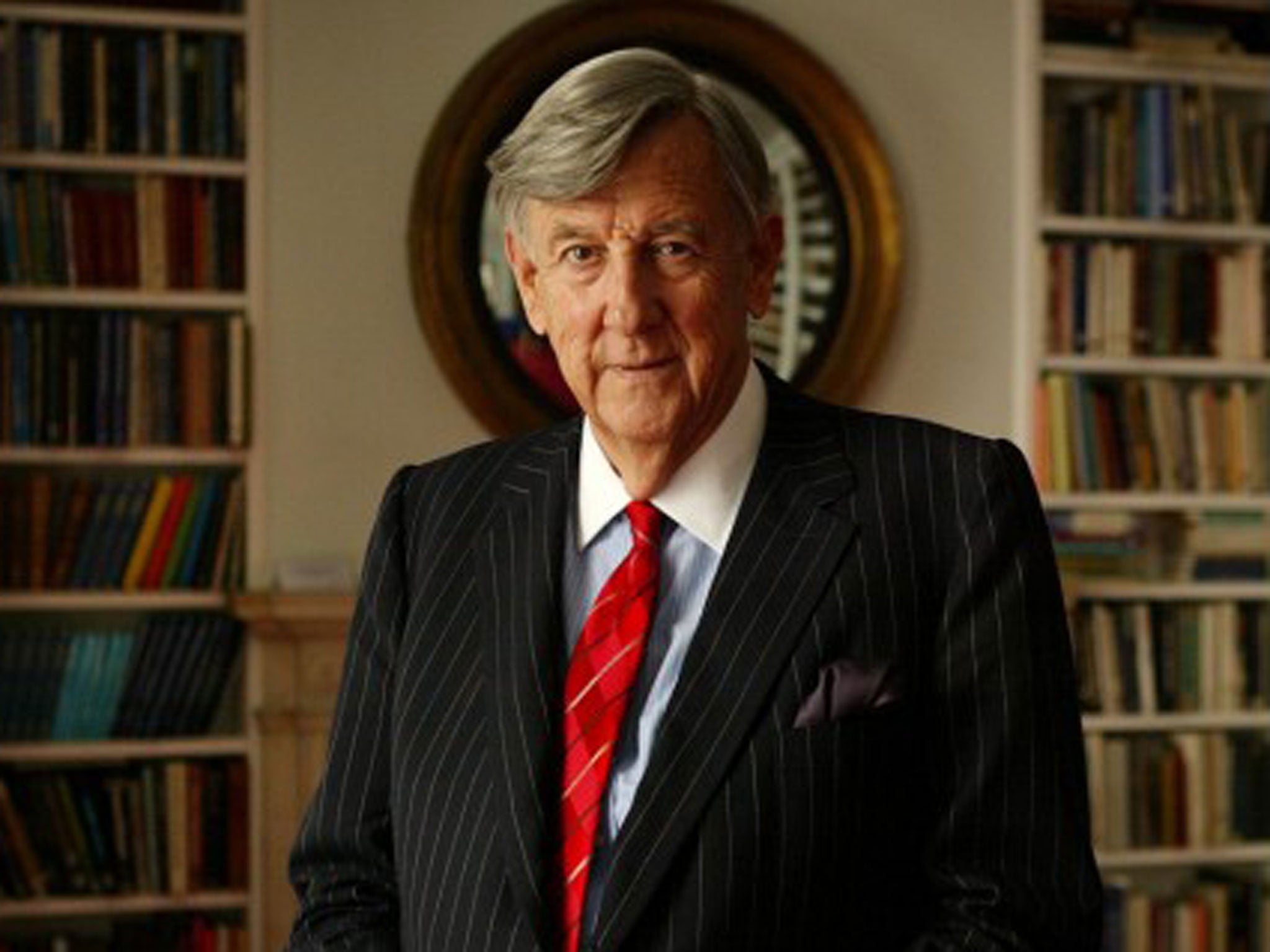

Dr James Martin: Technology guru and philanthropist who predicted the rise of the internet

His seminal work ‘The Wired Society’ was only one of more than a hundred books in his oeuvre

James Martin was a visionary writer and technologist whose book The Wired Society (1978), one of more than a hundred he wrote, predicted the arrival of the internet and of much other communications technology that is now commonplace. Later in life, having succeeded in solving business problems, he turned his focus towards finding solutions for the bigger issues facing the world today.

Martin was born in 1933 in Ashby-de-la-Zouch, Leicestershire, the son of a clerical worker. He gained a scholarship to read physics at Keble College, Oxford. He joined International Business Machines (IBM) in the late 1950s at a time when computers still filled whole rooms and required large teams of people to manage them.

By 1970 he was part of an elite group of computer scientists who were turning science fiction into reality, or, as he called it, “a think tank and internal university with an eclectic hornet’s nest of a faculty, opposite the United Nations building in New York”. He said of that time: “In the age of Nixon, we went to cocktail parties in the UN and it was like going to a different planet. The UN delegates had no clue about what was happening in technology, and we computer gurus had no vision beyond our own world.”

In 1977 he took a year off from IBM, during which time he wrote The Wired Society and ran the James Martin World Seminar series for executives about the new technology, which he foresaw revolutionising the world of commerce. The book was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and that year’s work earned him a million dollars, convincing him to go it alone. For the next 25 years he toured the world, lecturing to business people on current and future technologies.

His powers of prescience continued to bring him success. In 1996, just as the world wide web was taking off, Martin published his 100th book, Cybercorp: the New Business Revolution. He accurately predicted how this new technology would provide huge opportunities for business, yet cautioned that, “The more the basic mechanisms become automated, the greater the need for people to concentrate on uniquely human roles such as inventing new ways to delight the customers.”

In 2004 Martin made a gift of £60 million to Oxford University to fund a new school, the largest ever donation of its kind. The school has as its aims “to formulate new concepts, policies and technologies that will make the future a better place to be”. In an interview for this newspaper in 2011, in which he spoke of the need for research on the planet’s multifarious problems, he explained: “The idea behind the school was to say that all of these subjects needed research of very high quality, and on all of them there would have be to multidisciplinary research. Yet there was almost no multidisciplinary research going on in universities.” A further gift of £30 million came five years later.

Having spent much of his life writing and providing advice on communications technology and business, in recent years he had turned his writing focus towards the complex systems which make up our world. His most recent work, The Meaning of the 21st Century: A Vital Blueprint for Ensuring Our Future (2006) tackles these wider issues, emphasising the four main topics of natural resources, the double-edged sword of technological advances, the possible risks of this coming century and our prospects for the future. The film of the book, narrated by Michael Douglas, was released simultaneously.

He states in the book’s preface: “The 21st century is an extraordinary time – a century of extremes. We can create much grander civilizations or we could trigger a new Dark Age. There are numerous ways we can steer future events so as to avoid the catastrophes that lurk in our path and to create opportunities for a better world.”

But this is not some doom-laden prediction of disaster. Martin emphasises that it is within our capabilities to tackle these challenges using technologies which, for the most part, already exist. As with many issues, such as hunger, it is the political will to bring lasting solutions that is absent.

He continues in the preface, as if to emphasise the importance of his Oxford legacy, “A revolutionary transition is ahead of us, and our children have a vital role to play in it; so, there is so much that we need to teach them about their future.” Martin had lived on Agar’s Island, Bermuda, since buying it in 1997, using the technologies whose creation he had foreseen to keep in touch with the wider world. His body was found in the water near Hamilton Harbour by a kayaker. Police said there were no suspicious circumstances.

Professor Andrew Hamilton, vice-chancellor of Oxford University, said, “James Martin was a true visionary whose exceptional generosity established the Oxford Martin School, allowing researchers from across the disciplines to work together on the most pressing challenges and opportunities facing humanity. His impact will be felt for generations to come, as through the school he has enabled researchers to address the biggest questions of the 21st century.”

Professor Ian Goldin, Director of the school Martin helped create, added: “The Oxford Martin School embodies Jim’s concern for humanity, his creativity, his curiosity, and his optimism. Jim provided not only the founding vision, but was intimately involved with the School and our many programmes. We have lost a towering intellect, guiding visionary and a wonderful close friend.”

James Martin, writer, technology expert and philanthrophist: born Ashby-de-la-Zouch, Leicestershire 19 October 1933; married three times (one daughter); died Bermuda 24 June 2013.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments