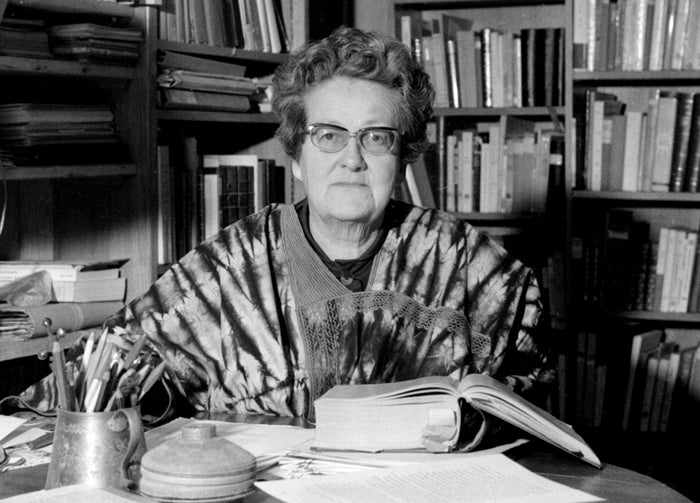

Germaine Tillion: Resistance fighter and ethnologist

On 13 August 1942, Germaine Tillion, a young French ethnologist and resistance fighter, was arrested by the German occupying authorities while at a Paris railway station, having been denounced by a maverick priest in the pay of the Abwehr intelligence organisation. Held at the La Santé and Fresnes prisons, on 21 October 1943 she was transported to the infamous women's concentration camp of Ravensbrück as part of the Nacht und Nebel ("Night and Fog") programme designed to eliminate without trace political opponents of Nazism.

Against incredible odds, she survived Ravensbrück, where possibly 90,000 women and children, including her mother, the writer Emilie Tillion, were murdered. To maintain spirits in the bleakest of environments, Germaine jotted humorous observations of daily events into a secret notebook which she read to fellow prisoners and which she turned into an operetta, Le Verfügbar aux Enfers ("The Campworker goes to Hell"). Although she later wrote at length about her experiences at Ravensbrück, she was reluctant for the operetta to become public (it was eventually performed in 2007) lest it gave people the misleading impression that life in the Lager was a frivolous affair.

There was no danger of that. Trained as an anthropologist, Tillion was an astute observer of human behaviour, a staunch defender of human rights and fierce critic of violence. After the Liberation, she criticised the use of torture in the Algerian war of 1954-62, and condemned human-rights abuses in the Gulags and post-2003 Iraq.

Tillion attributed her survival in Ravensbrück "to luck, to anger, to the desire to bring these crimes to light, and finally to the ties of friendship". A resourceful, independent and doughty character, she was born in 1907 into a bourgeois family from Allègre, a town in southern-central France. After studying archaeology and ethnology at university, in the 1930s she undertook a series of field trips to the remote eastern regions of Algeria, where she analysed the lives, customs and languages of semi-nomadic tribes. Strongly influenced by the teaching of the sociologist Marcel Mauss (nephew of Emile Durkheim) and the Islamic scholar Louis Massignon, she abhorred the racist philosophies which circulated freely in 1930s Europe. A trip to Bavaria in 1938 confirmed her loathing of Nazism.

Returning to France in 1940, she was sickened at the defeatism and moral cowardice of Marshal Philippe Pétain and his Vichy government. Determined to fight, she helped create the resistance movement based in the Paris anthropological institute, the Musée de l'Homme. Like many other underground groups, this sprang out of a professional network of colleagues who, unbeknown to one another, had come to a decision that something had to be done.

Initially directed by Boris Vildé, Yvonne Oddon and Anatole Lewitsky, the Museum of Man network, as it was later known, specialised in the distribution of propaganda, the manufacture of false papers, the passing of intelligence to London, the escape of allied airmen, the hiding of Jews and the publication of its own newspaper. These were perilous activities – the danger of infiltration by informers was constant. In early 1941, the main leaders were rounded up, and several shot, leaving Tillion in a senior role, but without much of an organisation. She developed links with other networks, such as Valmy and Ceux de la Résistance. Though women were numerous within resistance, they rarely occupied key positions. Tillion was an exception, something later acknowledged by the award of the Croix de guerre and Médaille de la Résistance.

Other decorations followed, including, in 1999, the Grand Croix de la Légion d'honneur, one of France's highest accolades and one infrequently bestowed on women. Such honours could hardly have been foreseen in the period just after the war when Tillion, having recuperated in Sweden, resumed her academic career, researching into the deportation of women from France, and again spending time in Algeria, where open warfare erupted in 1954.

Given her understanding of North Africa, it was only natural that the French government should have called upon her services and in 1955, she became part of the Governor-General's cabinet. Involved in the setting up of "social centres" to facilitate Franco-Muslim understanding and to ameliorate the distressing living conditions of Arab men and women, in 1957 she met secretly, and at great personal danger, Yacef Saâdi, one of the nationalist leaders, in a bid to halt the terror that was sweeping through Algiers. Though she was unable to stop the summary killings and public executions, that year Tillion took part in an inquiry into the use of torture in French North African prisons and holding camps. In 1960, Tillion joined the protests against the brutal treatment meted out to Djamila Boupacha, a young Algerian girl who had been raped with a bottle while in French custody.

Though she stopped just short of advocating full-blown Algerian autonomy, a standpoint which earned her censure from the left, it was hugely embarrassing to the French establishment that venerated resistance veterans such as Tillion openly condemned the Gestapo-like torture being perpetrated in Algeria. It was in part this criticism that persuaded French public opinion, or at least segments of it, that Algeria should be independent.

Tillion always retained her attachment to North Africa, writing extensively about the position of women in the region, who she believed were repressed not because of Christianity or Islam but because of the lingering vestiges of primitive society and a caste system. A prolific author, and the holder of a series of prestigious academic posts, at the Conseil National de la Recherche Scientifique and the Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes, she published her original pioneering research on the Berber tribes, much of which had been confiscated on arrest in 1942.

In her critique of the Nazi occupation and use of torture in Algeria, it has frequently been said that she was "the conscience of 20th-century France". A truly exceptional and courageous woman, towards the end of her long life she attracted considerable public interest, and was the subject of biographers and film-makers. In 2004, an Association Germaine Tillion was founded, partly under the aegis of Tzvetan Todorov, the Bulgarian-born intellectual. The association's website carries one of Tillion's own reflections: "All my life I have wanted to understand human nature, the world in which I was living."

Nicholas Atkin

Germaine Tillion, ethnologist and resistance fighter: born Allègre, France 30 May 1907; died Paris 19 April 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks