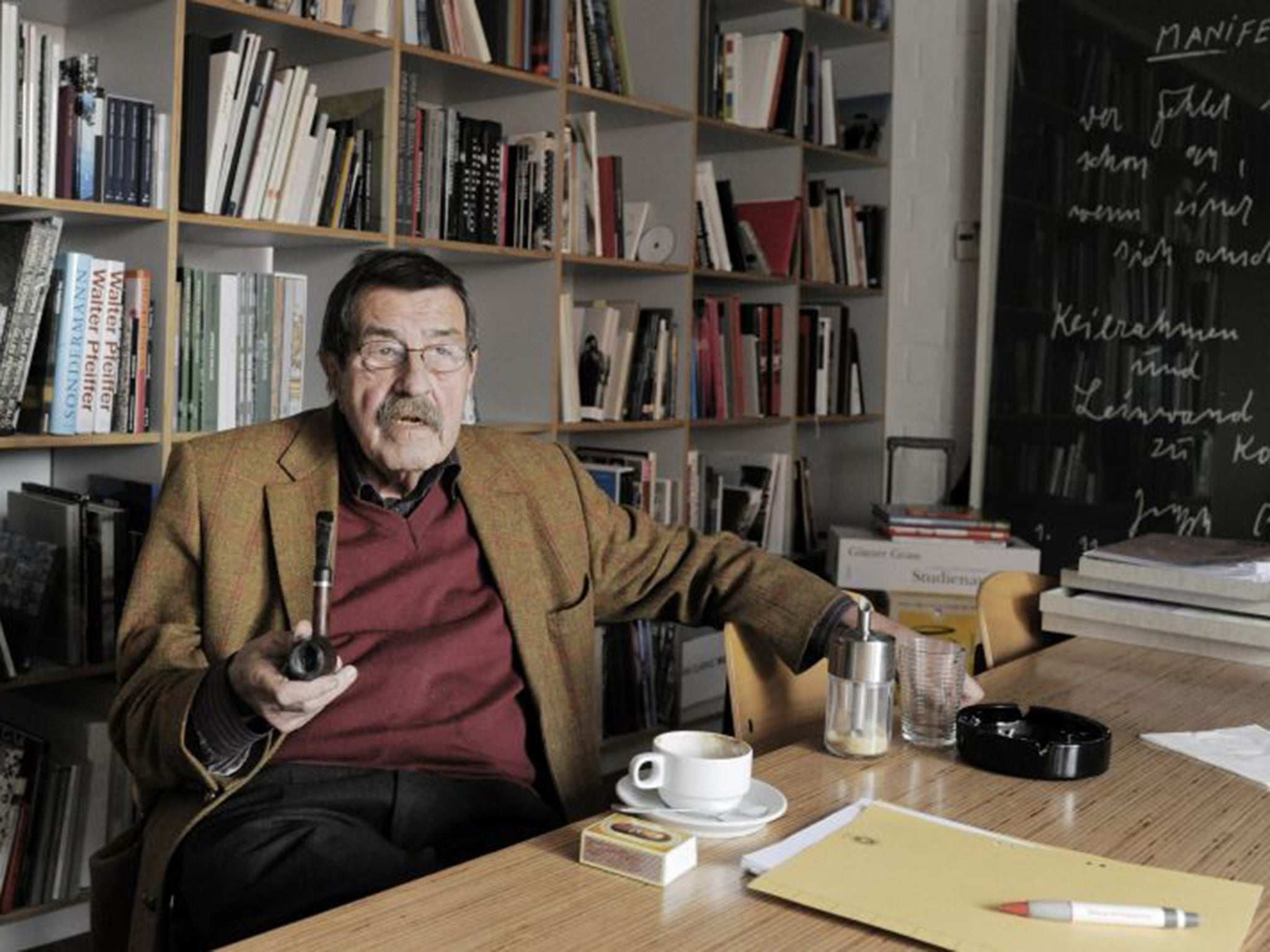

Gunter Grass: Writer whose work helped Germany find its postwar voice but was later attacked for his own wartime exploits

He was lauded by Germans for helping to revive their culture after the Second World War

The writer and artist Günter Grass gave voice to the generation that came of age during the Nazi era. But late in life he ran into controversy over his own wartime exploits and his stance towards Israel.

He was lauded by Germans for helping to revive their culture in the aftermath of the Second World War and helping to give voice and support to democratic discourse in the postwar nation. But he angered many in 2006 when he revealed in his memoir Skinning the Onion that as a teenager he had served in the Waffen-SS, the combat arm of the SS. “My silence through all these years is one of the reasons why I wrote this book,” he said at the time. “It had to come out finally.”

In 2012 he was criticised after he published a prose poem, “What Must Be Said”, in which he attacked what he saw as Western hypocrisy over Israel’s nuclear programme, describing the country as a threat to an “already fragile world peace” over its belligerent stance on Iran. Israel declared him persona non grata. He was born in Danzig (now Gdansk) in 1927 and grew up in this Polish-German town where his father was an import-export merchant dealing mainly with colonial countries.

After unsuccessfully volunteering for U-boat duty at the age of 15 he was conscripted into the Reich Labour Service and then into the Waffen-SS, training as a tank gunner. When the 10th SS Panzer Division Frundsberg surrendered at Marienbad in 1944 he found himself in a prisoner-of-war camp, where he took up stone-cutting and sculpture.

On release he studied art at the academies of Düsseldorf and Berlin, then went to Paris to paint and to start writing, returning to Berlin in 1960. He became a member of the Gruppe 47, the band of postwar writers formed by Hans Werner Richter to regenerate German literature after the fall of Germany.

Richter, who had spent the war in the US, attracted to himself the better left-wing writers, many of whom became politically active as well as producing a new literature that owed much to the influence of prewar expressionism and to the new absurdism that was arising in France. As well as a graphic artist with a rising reputation, Grass was primarily a playwright until 1959, the year when his most celebrated novel, The Tin Drum, was published.

His plays are often violent and grotesque, subliminally depicting aspects of life under Hitler in terms of metaphor; they can be described as a blending of absurdism and expressionism. His best-known is Uncle, Uncle, a depiction of a dedicated murderer who always fails to kill because none of his victims realise his intent or will give him the satisfaction of showing fear: it is they who kill him. The highest regarded is The Wicked Cooks, in which rival groups of cooks, looking for the secret recipe of a soup, realise that the soup is life itself and can be as varied as life: the experience of making it (or living life) is more important than its secret. There is much Christian mysticism behind the play.

The Tin Drum brought him international fame and best-sellerdom. It was influenced in its style more, perhaps, by Elias Canetti’s Autoda- Fé, one of the key works of 20th century grotesque literature, than by any other recognisable model; its mystique was perfectly attuned to postwar German experience and its memories of the Nazi years. It is the chronicle of a dwarf who from the age of three decides to stop growing and who starts to write his memoirs in a sanatorium at the age of 28.

An object of repulsion to his family and all around, he had lived through the Hitler period and the war and describes the events he witnesses from his singular state, sometimes very aware of the meaning of events, sometimes seeing them with a distorted vision. His language often apes the gibberish of Nazi ideology and reflects the distortions of reality that for many was the only way to live under the Nazi terror, believing anything anyone was told.

The Tin Drum was later adapted for the cinema by Volker Schlöndorff, winning the 1979 Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. The novel was followed by Cat and Mouse (1961) and Dog Years (1963), which together with The Tin Drum came to be called the “Danzig trilogy”. Whereas his dwarf in the first novel has a drum from the age when he stopped growing, which he constantly beats and which becomes an object of power over others, Cat and Mouse is dominated by the enormous Adam’s apple of Grass’s protagonist which leads him through a series of baffling events that again reflect the unreality of the Nazi period. In Dog Years the principal character, a stormtrooper in the early part of the book, acquires Hitler’s dog after the war and tours Germany with it on a campaign of denazification.

Later novels included The Diary of a Snail (1972) and The Flounder (1977), but Grass turned increasingly to poetry and back to the theatre, as well as writing books and articles on politics. The Plebeians Rehearse the Uprising is a play that satirises Brecht rehearsing a play about revolution while unaware of the real revolution taking form around him. As with many German intellectuals, Grass’s thinking about the problems of freedom, where so often the party that advocates it is more interested in power at any cost than democracy or principle, colours nearly all his writing.

Grass has sometimes been compared to Beckett, especially in his early plays and his poetry, but his work is far rougher, often deliberately so, and Beckett does not go in for extended metaphors in the same way. Grass is closer to Ionesco, and even more so to Kafka, but his roots also lie in the expressionist movement, with its larger-than-life caricatures of people and events and its search for a moral answer to the problems of the world. Grass’s most important collection of political writings appeared in 1968, and he produced many volumes of poems and diaries that record his thoughts and observations as well as his activities.

The Gruppe 47 Prize, which he won in 1958 for The Tin Drum, was followed by many others, including the French Foreign Literature prize in 1962 and the Theodor Heuss Prize in 1969. In 1999 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, the Swedish Academy describing him as a writer “whose frolicsome black fables portray the forgotten face of history”. He received honorary degrees from several universities, notably a doctorate from Harvard, and was honoured by writers’ institutions including PEN, in which he was very active.

Grass was much engaged in politics, and was best known for his support of Willy Brandt and the Social Democratic Party, for which he campaigned vigorously. He opposed the reunification of Germany in 1990, believing that it had been carried out too hastily. He was twice married, in 1954 to Anna Schwarz, a Swiss woman with whom he had four children, and in 1979 to Ute Grunert.

Throughout his life Grass continued to paint and draw and had many international exhibitions. The fine quality of his line work and his ability to bring an aura of menace to drawings of everyday objects has a relationship to his literature.

He produced several volumes of poetry with his own illustrations, and they belong together in such a way that with familiarity each seems deficient without the other. He not only designed the jackets for most of his own books but for those of other writers as well.

He was a large bear of a man, his face and figure familiar to every German, and he was undoubtedly attractive to women, as well as a good friend to artists in every sphere. Underneath the gruff exterior was great kindness, but it is for the sensitivity of his very German conscience, and his awareness of what Germany came to represent, during the nightmare of the 1930s and the War, that he most represents his country and its literature.

Günter Wilhelm Grass, writer and artist: born Free City of Danzig (Gdansk) 16 October 1927; Nobel Prize for Literature 1999; married 1954 Anna Schwarz (one daughter, three sons), 1979 Ute Grunert; died Lübeck, Germany 13 April 2015.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies