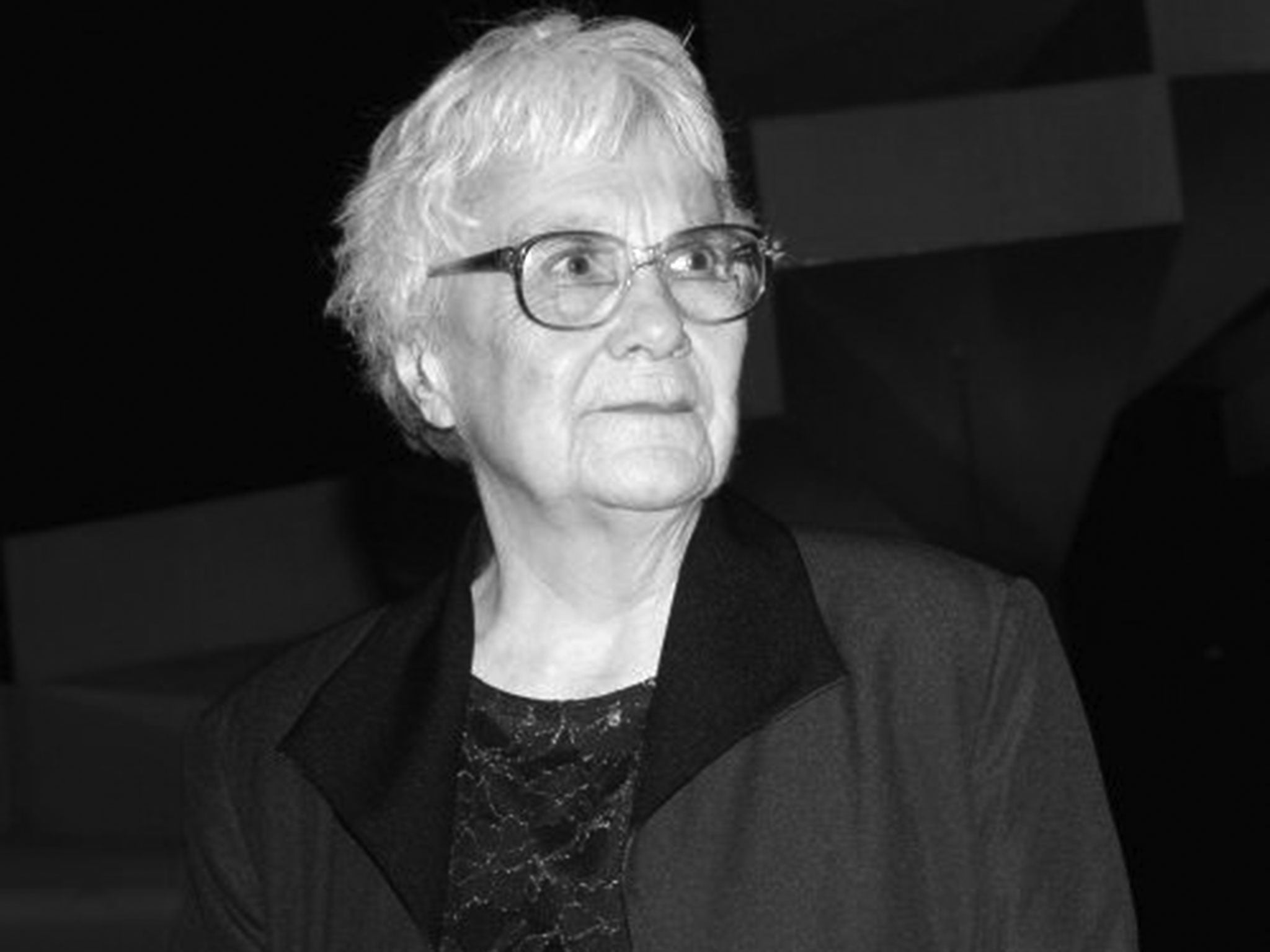

Harper Lee: Author who shot to fame with her novel 'To Kill A Mockingbird' but vanished from view for half a century

Unlike her friend Truman Capote, Lee did not revel in publicity, indeed she shied from it

The way in which a novel is ushered into the world can give scant indication of the fortune which it will find. Turn to the New Statesman of 15 October 1960, and there one finds Keith Waterhouse in the grip of reviewing a batch of new fiction. Between a backwards-told nouveau roman by Christine Brooke-Rose and a “cloth-cap” one by Catherine Cookson, he gave a paragraph to Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird. And is spot-on. “Miss Lee does well what so many American writers do appallingly: she paints a true and lively picture of life in an American small town. And she gives freshness to a stock situation.”

Even such a review cannot be enough to set in train that word of mouth which makes a book a necessary read, one which in Lee’s case was buoyed by becoming something that can often be a turn-off: a set-book in schools. Decades on, To Kill a Mockingbird has sold more than 30,000,000 copies but, for all the Civil Rights achievements, in which it played a part, this novel, set in the Depression, is no period piece (indeed, it inspired the name of a 1990s pop group, the Boo Radleys). It has all the small-town vivacity, a way with language, a recognition of idiom, which one associates with Harper Lee’s childhood friend Truman Capote, who appears as a character in her novel and whom she assisted with the work whose result was In Cold Blood.

And that was enough for Harper Lee. Not for her the compulsion to pour forth more, and hope that the one true book will rise above that subsidiary swamp. The book’s spirit was well caught by Waterhouse: “The innocent childhood game that tumbles into something adult and serious is a fairly common theme in fiction, but I have not for some time seen the idea used so forcefully as in To Kill A Mockingbird... The game is ‘Making Boo come out’, which the children of a Southern lawyer play outside the old home of a family of foot-washing Baptists where, according to one too many legends, Boo Radley has been kept chained up for years and years for stabbing his father with a pair of scissors. Pretty soon we are in the adult game, based on the same fear and fascination of the dark: the ugliness and violence of a Negro’s trial for rape and the town’s opposition to the children’s father for defending him.”

All this had its roots in Lee’s upbringing in Monroeville, Alabama, where, the youngest of four children, she was born in 1926. Her father, Amasa, was a lawyer, while her mother’s maiden name of Finch became that of the widowed family in the novel; the girl – Scout – was a version of Harper herself (or Nelle as she was then known). Her father, who was born in 1880, had once part-owned and worked on the Monroe Journal and been a state senator. Her mother, a huge woman preoccupied with crossword puzzles, was of a strange mind: she would wander up and down the street, saying things to one and all, and had twice tried to drown the future writer, a fate from which she was saved by a sister.

All this was certainly the stuff of that grotesquerie which is the stock-in-trade of Southern fiction, as shown in the work of Capote who, as a child, was a neighbour of the tomboy Lee. She had taunted him at first until realising that, with a mutual passion for reading, he was a kindred spirit. They spent many hours in tree-house retreat, reading aloud to each other.

In her novel, the character Dill is inspired by memories of Capote at this time: “He wore blue linen shorts that buttoned to his shirt, his hair was snow white and stuck on his head like dandruff; he was a year my senior but I towered over him... His laugh was sudden and happy... We came to know him as a pocket Merlin, whose head teemed with eccentric plans, strange longings, and quaint fancies.”

She was educated at local schools, and, after a year at Huntingdon College in the mid-1940s, spent the rest of the decade studying Law at the University of Alabama, followed by an exchange year at Oxford, which she left early, when, deciding against the family profession, she set about a writing career. She moved to New York, getting work as a reservations clerk for airlines and living in a cheap apartment.

This had to be combined with trips home, for, shortly after the deaths in 1951 of her mother and a brother, her father became ill. These visits galvanised the novel upon which she had begun work, one which was also rooted in memories of the Scottsboro rape trials which had made a strong impression upon her in 1931.

Her writing, in which one can reasonably find a kinship with Capote’s, resulted in something which a publisher thought fragmentary: stories rather than the novel that they should, and did, become. Supported by money from friends, she continued with it for another two years, and more, and To Kill A Mockingbird was published in 1960.

Meanwhile, before its publication, at this time of intense creativity, Capote had spotted an item in the New York Times one November day in 1959 about the murder of the Clutter family in Holcomb, Kansas. The killers had yet to be caught. His imagination was immediately sparked by this small-town case, and he arranged with The New Yorker to go there forthwith for a report on it. Little did Capote realise where it would lead, but he did know from the start that he would require some help, for his manner by now was hardly conducive to getting police officers to open up. Lee, whose interest in crime is evident in her novel, readily agreed to go with him.

Capote was greeted with suspicion and derision, not least by Alvin Dewey of the Kansas Bureau of Investigation. Hackles rose and were soothed by Harper, and people came to appreciate her strange friend. Even Dewey did so, and he became a lifelong friend of Lee’s. Capote’s interviewing method – an echo of Boswell – eschewed tape-recorder or note-taking, for these made people self-conscious.

Instead, after each interview he and Lee would return to their lodgings, each writing up an account of what they had heard, and then, over drinks, compare their versions, from which the narrative would later be built. All of this – after a memorable Christmas dinner which led to their being accepted by Holcomb people – was galvanised, and protracted, by the arrest at the year’s end of Dick Hickock and Perry Smith, who were hanged in 1965.

In Cold Blood was published the following year, accompanied by a celebrated masked ball at the Plaza in Manhattan – a far cry from a Kansas jail. Among the guests at a party to which many lobbied for an invitation was, of course, Harper Lee. By this time, her novel was a worldwide success, and had been turned into a good, if toned-down film with Gregory Peck, whose preparation for the role of lawyer had included a visit to her father, who died in 1962 at 81. (Robert Duvall played Boo Radley, while some characters were dropped.)

Unlike Capote, Lee did not revel in publicity, indeed she shied from it and, if she was working on anything, she did not announce it, while his purported Proustian epic, Answered Prayers, turned out to be slim, if engaging pickings. (The childhood friends last met some 15 years before his death in 1984.) In a life of unostentatious privacy, she spent time in playing golf, enjoying music and collecting the memoirs of 19th century clergymen.

The title of To Kill a Mockingbird is an emblem of the humanity which pervades the novel (personified in the widowed father, lawyer Atticus), and some have said that there is a contradiction in so evocative a style, one which turns a neat effect on every page, purporting to be a child’s eye view of events. Lee, however, with her fascination with the Scottsboro trial – in which nine black teenagers were wrongly accused of the rape of two white women – was a precocious child, and, in this recollection and re-creation of the Thirties (Hitler has an off-stage part), she convincingly depicts Scout as alert to all around her, to that strangeness which is the South: author and child unite:

“At the end of the road was a two-storied white house with porches circling it upstairs and downstairs. In his old age, our ancestor Simon Finch had built it to please his nagging wife, but with the porches all resemblance to ordinary houses of its era ended. The internal arrangements of the Finch house were indicative of Simon’s guilelessness and the absolute trust with which he regarded his offspring.”

There is, throughout, a precision, such as: “Her bottom plate was not in, and her upper lip protruded; from time to time she would draw her nether lip to her upper plate and carry her chin with it. This made the wet move faster...” (this neighbour was dropped from the film). None of this slackens the pace of a book which is equally adept at describing a long summer as it is at a trial whose dialogues occupy the second part.

The novel is effortlessly in tune with a South where, as Lee writes, “Atticus picked up the Mobile Press and sat down in the rocking chair Jem had vacated. For the life of me, I did not understand how he could sit there in cold blood and read a newspaper when his only son stood an excellent chance of being murdered with a Confederate Army relic. Of course Jem antagonised me sometimes until I could kill him, but when it came down to it he was all I had.”

In 2013, Lee filed a lawsuit to regain the copyright to Mockingbird from a son-in-law of her former literary agent who she said had “engaged in a scheme to dupe” her into assigning him the copyright in 2007, when her hearing and eyesight were failing and she was living in an assisted care facility after suffering a stroke. The suit was settled out of court.

In 2015, after more than half a century of silence from Lee, Go Set A Watchman was published. It was at first billed as a sequel, but it soon became apparent that although it concerned an adult Scout returning to her home town from New York, it was in fact Lee’s first draft of To Kill A Mockingbird.

Though there were reports that Lee had had little to do with its appearance, she put out a statement through her lawyer, Tonja Carter, which read: “In the mid-1950s, I completed a novel called Go Set a Watchman. It features the character known as Scout as an adult woman and I thought it a pretty decent effort. My editor, who was taken by the flashbacks to Scout’s childhood, persuaded me to write a novel from the point of view of the young Scout. I was a first-time writer, so I did as I was told. I hadn’t realised it had survived, so was surprised and delighted when my dear friend and lawyer Tonja Carter discovered it.” Friends remained suspicious, and though it initially sold extremely well it was very poorly received by critics.

This, though, will never detract from Lee’s achievement with To Kill A Mockingbird. The great success of the novel is that, as Keith Waterhouse immediately saw, it transcends time, showing that actions, perpetrated by young or old, take many forms: even apparent innocence harbours a spirit which can result in cold blood.

CHRISTOPHER HAWTREE

Nelle Harper Lee, author: born Monroeville, Alabama 28 April 1926; died Monroeville 19 February 2016.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments