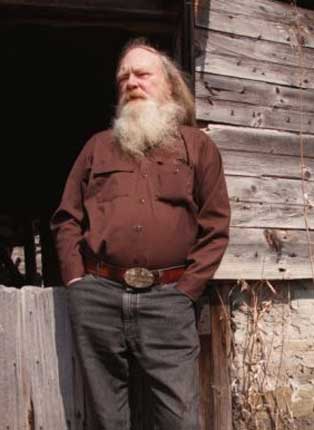

Hayden Carruth: Poet who produced work of 'unapologetic affection' despite lifelong struggles with mental illness

Hayden Carruth was a gentle, gifted man (though with a marvellously ornery side) who suffered such inner mental torment that he wiped himself off the American poetic map for many years.

It was only in relatively old age that he enjoyed the acclaim and rewards his talent deserved, though by then he had developed what a profile writer described as an enduring "respect for disappointment." His mental suffering was comparable to that of his more famous contemporaries (John Berryman and Robert Lowell in particular), but there was never any career benefit in it for Carruth, and his final flourishing occurred despite his psychological troubles, not because of them.

He was born and grew up in Connecticut, the son and grandson of newspapermen. It was an insular but emotionally distant family, and Carruth later claimed that what first drew him to writing was the prospect of being able to communicate with a warmer outside world. Attending college at the University of North Carolina, he worked on the student newspaper but also discovered W.B. Yeats and poetry. After serving in Italy uneventfully for the last two years of the Second Word War, he went on the GI Bill to the University of Chicago, where he took an MA in English in 1948. He also learned the clarinet and began a lifelong love affair with jazz, which he saw as music's counterpart to poetry.

Taking a job on the staff of Poetry magazine, Carruth was rapidly promoted to editor in 1950 and his own work began to appear in the small literary magazines that burgeoned in post-war American universities. But he was already suffering from anxiety disorders which, in a pre-pharmacological age, psychoanalysis did nothing to dispel. A fellow student later told how when Carruth's daughter was born he had been pressed into service to carry the baby from the hospital to Carruth's car – "Hayden was too terrified to hold her."

Carruth's editorship of Poetry lasted less than a year, curtailed by his increasingly erratic behaviour, which included making complaining phone calls at late hours to the magazine foundation's staid trustees. Removed from the post, he joined the University of Chicago Press, learning copy-editing and proof-reading skills that later stood him in good stead as a freelancer. His wife Sara Anderson left him, taking their small child with her back to the South, and he soon took up with Eleanore Ray, with whom he moved to New York, where he found work again in publishing.

The phobic anxiety besetting him soon proved overwhelming, and in 1953 he voluntarily committed himself to a psychiatric institution in upstate New York named (improbably) Bloomingdale. His treatment was perfunctory; though encouraged by the doctors to write (years later these poems appeared as The Bloomingdale Papers, 1975) Carruth was otherwise left alone; superficially recovered, he soon relapsed, and received electro-shock treatment that did little for him except damage his memory. On release, he said later, he still felt bewildered and frightened by the world.

His second marriage having failed, Carruth took refuge in his parents' house outside New York City, living in an attic room for five years, crippled by phobic fears that made engagement with the external world seemingly impossible. Years later he wrote: "Agoraphobia is when every night at 2:00 a.m. for five years – that's 1,825 nights – you go out loaded with Thorazine to walk in the street ... and you never get more than a hundred yards from your door."

Yet he managed at last to emerge, moving initially to a cottage on the Connecticut estate of James Laughlin, the founder of the publisher New Directions, for whom Carruth did filing. He also met his third wife and had a son. His first collection, The Crow and the Heart (1959), came out to an encouraging critical reception, but his mental health was still precarious, and he and family soon moved to northern Vermont – not to the pastoral scenic land of the southern parts of the state, but to its poor and unpopulated northern wilderness, where they lived only 25 miles from the Canadian border. Although he felt better, Carruth later explained, he had only managed a "shift from reclusion to seclusion."

Despite his initial concerns about how he would be received, Carruth got on well with the locals, and became fast friends with a neighbouring farmer named Marshall, who featured in many of his poems. Carruth scratched out a living through a mixture of freelance editorial work and typing, and by raising chickens and ducks and selling eggs. The physical work on his smallholding was unremitting; he later estimated that it took him one month each year to chop enough wood to heat his house through the winter, and he wrote about this work – from woodcutting to piling manure – with unromantic precision, and sometimes rage:

And I stand up high

on the wagon tongue in my whole bones to say

woe to you, watch out

you sons of bitches who would drive men and

women

to the fields where they can only die.

And like his fellow Vermont poet Robert Frost, he could be almost gruesomely unsentimental:

I have a friend

Whose grandmother cut cane with a machete

And cut and cut, until one day

She snicked her hand off and took it

And threw it grandly at the sky.

He was writing prolifically now, staying up through much of the night in the few hours he could find, and his work appeared in magazines such as The New Yorker and in several book-length collections. Isolated as he was, he never lost touch with the writer friends he had made in Chicago and New York – the poets Henry Rago, Wendell Berry, Adrienne Rich, Denise Levertov – though he rarely left Vermont and in any case could not afford to travel.

Eventually, in the 1970s, he landed a few part-time teaching jobs in Vermont; then in 1979 he went to Syracuse to join its writing programme, leaving his marriage behind in Vermont. If not the making of him, the appointment proved the making of his reputation, and he found publication and profile suddenly easier.

He was already the poetry adviser to The Hudson Review and became the poetry editor of Harper's for six years. He had a good eye for unexpected jewels found among the literally thousands of poems that cascaded through the mail slot of the magazine, and his taste was eclectic; as he described his method of selection for his major anthology The Voice That Is Great Within Us (1970), his prime criterion was "to select no particular poem that does not seem to me genuine within its given modality, whatever that may be."

Always candid about himself, Carruth was repelled by affectation, in both literary and social life. Influenced by Camus, whom he had read voraciously during his convalescence in the 1950s, Carruth was obsessed with "authentic" voices, which for him cut across facile characterisations of writers. Loathing dogma, he avoided membership in any "school" of poetry, and as a poet himself, Carruth crossed many of the normally rigid dividing lines of American poetry. He was technically accomplished but usually preferred a free verse that was none the less carefully structured.

With the onset of old age, there is an intensified lyricism to Carruth's own poems that is the more moving because unpredictable – especially in the late collection Scrambled Eggs & Whiskey, which won the National Book Award in 1996. The deceptive simplicity of his diction can suddenly give way to an understated but beautifully unusual turn of phrase, as in one poem when he rejoins his ex-wife of 30 years before at the hospital bed of their dying daughter, and sees that this meeting "is still a symbol/of that magical sum we were."

He was by turns rueful and playful about his growing infirmities, noting that now he was "straining broken/ cork from my wine with broken teeth" yet continuing to work with energy and undiminished poetic ambition – shown in the two-line poem "The Last Poem in the World":

Would I write it if I could?

You bet your glitzy ass I would.

Carruth's mental troubles never entirely went away, and after the failure of a relationship in 1988 he attempted suicide. Then in his fourth and final marriage, to the younger poet Joe-Anne McLaughlin, he found an unexpected and enduring happiness. What Wendell Berry called the "unapologetic affection" of his work grew even larger in these later years, despite a maverick's despair about the political condition of America (in 1998 he refused an invitation to the Clinton White House, appalled at what he saw as the administration's undervaluing of the arts).

Reading the later Carruth, one sees that he is after verities, but is too modest to claim any special insight. What remains, however, is a very special voice:

...But of course we always tell

each other what we already know. What else?

It's the way love is in a late stage of the world.

Hayden Carruth, poet: born Waterbury, Connecticut 3 August 1921; Editor, Poetry, Chicago 1949-50; Visiting Professor, Johnson State College, Vermont 1972-74; Visiting Professor, University of Vermont, Burlington 1975-78; Poetry Editor, Harper's 1977-82; Professor of English, Syracuse University, New York 1979-91; married 1943 Sara Anderson (one daughter deceased; marriage dissolved), 1952 Eleanore Ray (marriage dissolved), 1961 Rose Marie Dorn (one son; marriage dissolved), 1989 Joe-Anne McLaughlin; died Munnsville, New York 29 September 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks