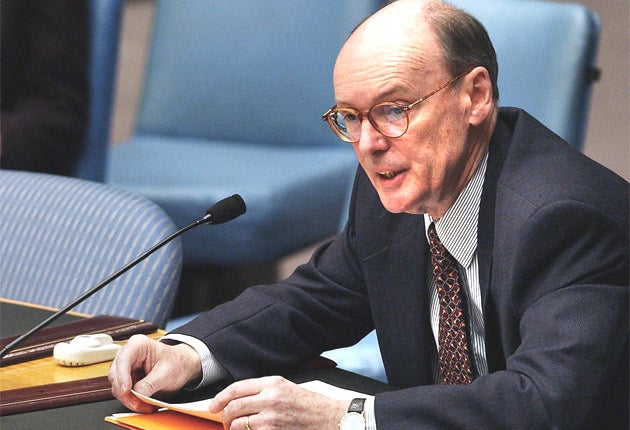

Hédi Annabi: Head of the United Nations Stabilisation Mission in Haiti

The Secretary General's Special Representative in Haiti, Hédi Annabi, was one of those exceptional people who work quietly and determinedly in the background, largely unknown to all but their United Nations staff. Unlike the well-known Sergio Vieira de Mello, the Assistant Secretary General killed in Baghdad in 2003, there was nothing flamboyant about Annabi. He did not like publicity.

Annabi was nearing the end of a 30-year career in peacekeeping when in 2007 he was appointed to head the UN Stabilisation Mission in Haiti, known by its French acronym, Minustah. It had been created by the Security Council in 2004 for an impoverished country that experienced almost continuous violent political turmoil and natural catastrophe.

The mission comprised some 9,000 uniformed personnel, including troops and police and 500 civilians; the mandate was to help secure a stable political environment, to facilitate humanitarian assistance and to contribute to public safety, law and order. In every UN mission it is the job of the Special Representative to implement the political objectives decided by the Security Council, to provide cohesive, consistent leadership and operational guidance. Annabi was considered the ideal choice.

He was nicknamed "the headmaster" by some of those who worked for him. He was slight of build, balding and wore glasses and liked to mentor chosen international civil servants, some of whom serve today in key UN peacekeeping positions. A notable skill was his capacity to thoroughly brief on any given situation and he always presented the facts, unadorned. He could be blunt without being offensive and while his staff cherished his sense of humour, they also noted his ability to be ironic without being cynical.

He had lived a conventional life in the suburbs of New York, an hour by train from his office on the 36th floor of the Secretariat. He served long hours and after the serious illness of his wife Danièle he was always available at home.

Annabi was a Tunisian national. He attended the Institute d'Etudes Politiques in Paris and later the Graduate Institute of International Studies in Geneva, where he studied international relations. He served in the Tunisian Foreign Ministry before joining the UN Secretariat in 1981. It was the most difficult of times. The withholding of US dues by an anti-UN Congress saw the organisation in crisis-management. There were years of cutbacks and job losses with scores of officials juggling funds simply to keep the doors open. There were serious institutional weaknesses, no infrastructure for emergency operations and no contingency planning. But at the end of the Cold War there had been a rapid growth of UN peacekeeping and by 1994 there were some 71,500 peacekeepers in 17 different trouble spots. These troops were shouldering new burdens, including nation-building. Annabi, who had taken part in the UN-brokered political settlement in Cambodia, would help to create one of the most ambitious missions, the UN Transitional Authority in Cambodia.

In 1993 Annabi was appointed Director of the Africa Division in the Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO), and was responsible for overseeing the UN Assistance Mission for Rwanda (Unamir), created in October of that year. He never wavered from the view that the 1994 genocide of the Tutsi could have been avoided if timely reinforcements had been provided to the Canadian Force Commander, Lt-General Roméo Dallaire.

For the three months the genocide lasted Annabi had been in almost daily contact with Dallaire and his tiny garrison of volunteer UN peacekeepers in the capital, Kigali. Annabi had only bad news. The US and UK governments had been determined to block even minimal help and argued that the UN was over-stretched – particularly in former Yugoslavia – and Rwanda too dangerous. Annabi had patiently explained how even a handful of Tunisian Military Observers was successfully preventing Hutu Power mobs from killing refugees sheltering at the Hôtel des Mille Collines. "We were dealing with thugs with machetes", he said.

Two years later he told me that the provision of such a weak and ill-equipped mission had been "like trying to cure cancer with an aspirin". He had broken down in tears in our interview. It was a rare off-guard moment. He was generally diplomatic about member governments but in this instance both politicians and the press had roundly blamed the UN for Rwanda and had turned on those in the Secretariat who had been in positions of responsibility. The circumstances of the genocide marked him forever but he chose not to join in the subsequent hand-wringing discussions, continuing instead with his daily job of trying to obtain international help for some of the world's worst places.

In 1997 he was appointed deputy head of DPKO with responsibility for supervising all UN missions, including the onerous task of helping to interpret the mandates issued by the Security Council. He was well-acquainted with such mandates. They could be of mind-numbing ambiguity and could sometimes put UN personnel at risk in unstable circumstances. He knew how often they were written with scant consideration for the realities on the ground when the Council sent peacekeepers into situations with orders they could not follow, and which the Council refused to change. He had a steady nerve. It was essential.

Exactly 15 years after Rwanda's genocide had begun Annabi was once more pleading the cause of a fragile, poverty-stricken, densely populated and violent country. On 6 April 2009, as the head of Minustah he had appeared before the Security Council and in a moving address had told member states that Haiti was at a turning point. This was, he said, the best chance in years to "break from the destructive cycles of the past to a brighter future". He argued that Haiti needed sustained international en-gagement; without an improvement in the daily lives of the Haitian people there would be no long-term security.

In his last press conference, on 5 January, his message was of hope. In a few months the UN Stabilisation Mission was to have assumed responsibility for presidential and legislative elections. If this process failed because of "personal political ambition or the scourge of corruption" the work of the UN would have been in vain, he said. "I am, however, convinced that these obstacles can be overcome and the promise of a better future for Haiti is not naive, if all Haitians engage themselves resolutely in a dialogue of understanding and cooperation and if they turn their backs to doubt, mistrust and suspicion". Annabi knew better than anyone that in UN peacekeeping the transition period was the most dangerous, the time when extremists try to derail the peace.

He was killed in the UN building in the Christopher Hotel, Port-au-Prince, which collapsed when the earthquake struck late in the afternoon of 12 January. He had been on the top floor.

Linda Melvern

Hedi Annabi, diplomat: born 4 September 1944; married (one adopted son); died Port-au-Prince, Haiti 12 January 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments