Hugo Chavez: Paratrooper and coup leader later elected as populist president

Hugo Chavez was a 38-year-old lieutenant-colonel in 1992 when he tried to overthrow the government of President Carlos Andres Perez, saying it was corrupt, served only the nation’s élite and treated the poor majority like doormats. He failed, was court-martialed and spent two years in jail, but he had struck a chord with the masses. As a civilian almost exactly seven years later, on 2 February 1999, he was sworn in as president after being democratically elected in a landslide vote. That also made him commander-in-chief of the armed forces where he had started as a 17-year-old cadet.

In office, he launched what he called a “Bolivarian Revolution” based on the ideas of the 19th century Venezuelan Simon Bolivar, the heroic liberator of the northern nations of South America from the Spanish conquerors. He nationalised key industries, including oil – Venezuela is among the world’s top 10 oil producers and in 2011 claimed to have more reserves than Saudi Arabia – and he ploughed much of the income into social reform projects, literacy campaigns, subsidised food programmes and land redistribution.

During his first 30 months in power, fearing a Castro-style regime, some 200,000 wealthy or middle class Venezuelans emigrated – mostly to the US, Australia or Western Europe – taking with them tens of billions of dollars. (The nation’s own currency has long been called the Bolivar and Chavez renamed the country the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela.)

Despite polarising the nation between the poor, who said he had become their first-ever voice, and the middle class and wealthy, who described him as an autocratic “clown prince”, he retained power thereafter through elections, and also referendums, notably the one that allowed a change in the constitution to allow presidents to keep running indefinitely. He won a fourth election in October 2012; in 2011 he had said he was bound to win, and expected to still be in power in 2030. “It is written,” he said. “It is fixed,” retorted his opponents.

Almost from his first day in power, Chavez became a kind of messiah to the Venezuelan poor and something of a darling of the international Left, while an increasingly irritating thorn in the flesh of capitalist leaders and institutions. His opponents accused him of launching “robolution rather than revolution”, saying his family had got rich off the state. He was soon up there on Washington’s hate list, vying with Saddam Hussein, Colonel Gaddafi and even Fidel Castro. Calling former president George W Bush a “donkey” and an “asshole” kept Chavez off the White House Christmas card list but added to his popularity among his supporters at home, who were known as Chavistas. He famously issued a message to the British Prime Minister of the time: “Mr Blair, you are an imperialist pawn who attempts to curry favour with Danger-Bush-Hitler, the number one mass murderer and assassin on the planet.”

On 11 April 2002 he briefly resigned during a coup against him, which he blamed squarely on George W Bush, but mass Chavista demonstrations around the nation meant he was back in office two days later. There was no doubt Bush, who promptly recognised the administration which tried to replace him at that time, would have loved to see the back of him. On the other hand, Venezuela’s state oil company, Petroleos de Venezuela, is a key supplier of crude oil to the US and owns the Citgo chain of around 14,000 petrol stations across the US.

The Americans had long accused Chavez of supporting Colombian “narco-guerrillas”, but Chavez’s aides insisted he merely had “an arrangement” with the guerrillas for the sake of border security. In 2005, the US televangelist Pat Robertson, overruling one of the Ten Commandments, famously called for his assassination.

As for Chavez himself, no one was ever quite sure who or what he was. His former psychiatrist, casting doctor-patient confidentiality aside because he apparently felt he was revealing his president’s sensitive side, once said the nation’s leader often wept in his presence. “Hugo needs to be idolised,” said the psychiatrist, Dr Edmundo Chirinos. “He’s a narcissist. He’s impulsive, temperamental, hypersensitive to criticism. Knocking down Bush, for example, was his way of putting himself on the same level [as Bush].”

In another interview, with the New Yorker magazine, Dr Chirinos said Chavez had a near-photographic memory and rarely slept more than three hours a night. “His character is unpredictable and disconcerting. We can know him in depth only if we join the criticism of his adversaries with the idolatry of his followers and strain them through the colander of logic and objectivity.”

After meeting Chavez, the great Colombian writer Gabriel Garcia Marquez wrote: “Suddenly I understood that I was speaking to two very distinctive men in one person. One to whom destiny gives the possibility of saving his country; the other who is capable of going down in history as a despot.” A journalist who knew him recalled that Chavez once told his Defence Minister: “Send 10 battalions to the Colombian border for me.” “It was like he was ordering a pizza,” the journalist wrote.

Chavez became increasingly flamboyant, better known for his red open-neck shirts or track suits than for the traditional presidential garb. When he visited Vladimir Putin in Moscow in 2001 and Putin stuck out his hand for the traditional greeting, Chavez jumped into a karate stance: “I hear you have a black belt in karate,” he said. Changing his stance to make a baseball swing, he added with a wide grin. “I’m a baseball man myself.”

Whereas Castro would show up around Cuba and give six-hour, unscripted speeches, Chavez adopted modern technology. He launched a live weekly TV show – Alo, Presidente – which became a mixture of chat show, reality TV, song and dance. It was often he himself who sang and danced and the show would go for as long as he felt like it – often up to six hours, and into the wee hours.

Hugo Rafael Chavez Frias was born on 28 July 1954, in Sabaneta, a small farming village in Venezuela’s western state of Barinas to parents who were, like most Venezuelans, mestizo Creole – of mixed descent from native Indians, the Spanish conquistadores and African slaves. Like most Venezuelans, “Soy blanco, negro y indio,” [“I am white, black and indian”] he was later wont to say when he toured the nation as president.

Both his father, Hugo de los Reyes, and his mother, Elena Frias, were teachers, but that barely kept them above the poverty line. Young Hugo spent his early years living in an adobe home with a palm frond roof owned by his devoutly Catholic grandmother Rosa, a major influence on his life, whom he once described as “a pure human being, pure love, pure kindness.” His family wanted him to train as a priest and, with that in mind he served as an altar boy in the local church. “At her [his grandmother’s] side,” he recalled years later, “I got to know humility, poverty, pain, sometimes not having anything to eat. I saw the injustices of this world.”

Because of his thin frame but large feet, his classmates at the Julian Piño primary school nicknamed him Tribilin, the South American Spanish name for the Disney character Goofy. His family then sent him to the city of Barinas to attend the state’s only high school, the Daniel O’Leary School, named after an Irish general from Cork who had served under the liberator Bolivar. Chavez later admitted that his time at high school revolved around “my studies, girls and baseball.”

His favourite book was Robinson Crusoe. As it turned out, neither his studies nor girls took him out of a likely lifetime of poverty. It was baseball, Venezuela’s most popular sport, at which he excelled. It did not bring him his dream of being a pitcher for the San Francisco Giants but it did win him a scholarship to the Venezuelan Academy of Military Sciences as a cadet at the age of 17.

He graduated with a degree in military science and engineering in 1975, with the rank of sub-lieutenant, and quickly rose through the army ranks to become commander of an élite paratrooper unit. He married his childhood sweetheart Nancy Colmenares, also from a poor family in Sabaleta, in 1977, and they had three children. Their marriage collapsed while he was in prison in the early 1990s, mostly because of his earlier, highly public 10-year-affair with a well-known half-German historian, Herma Marksman.

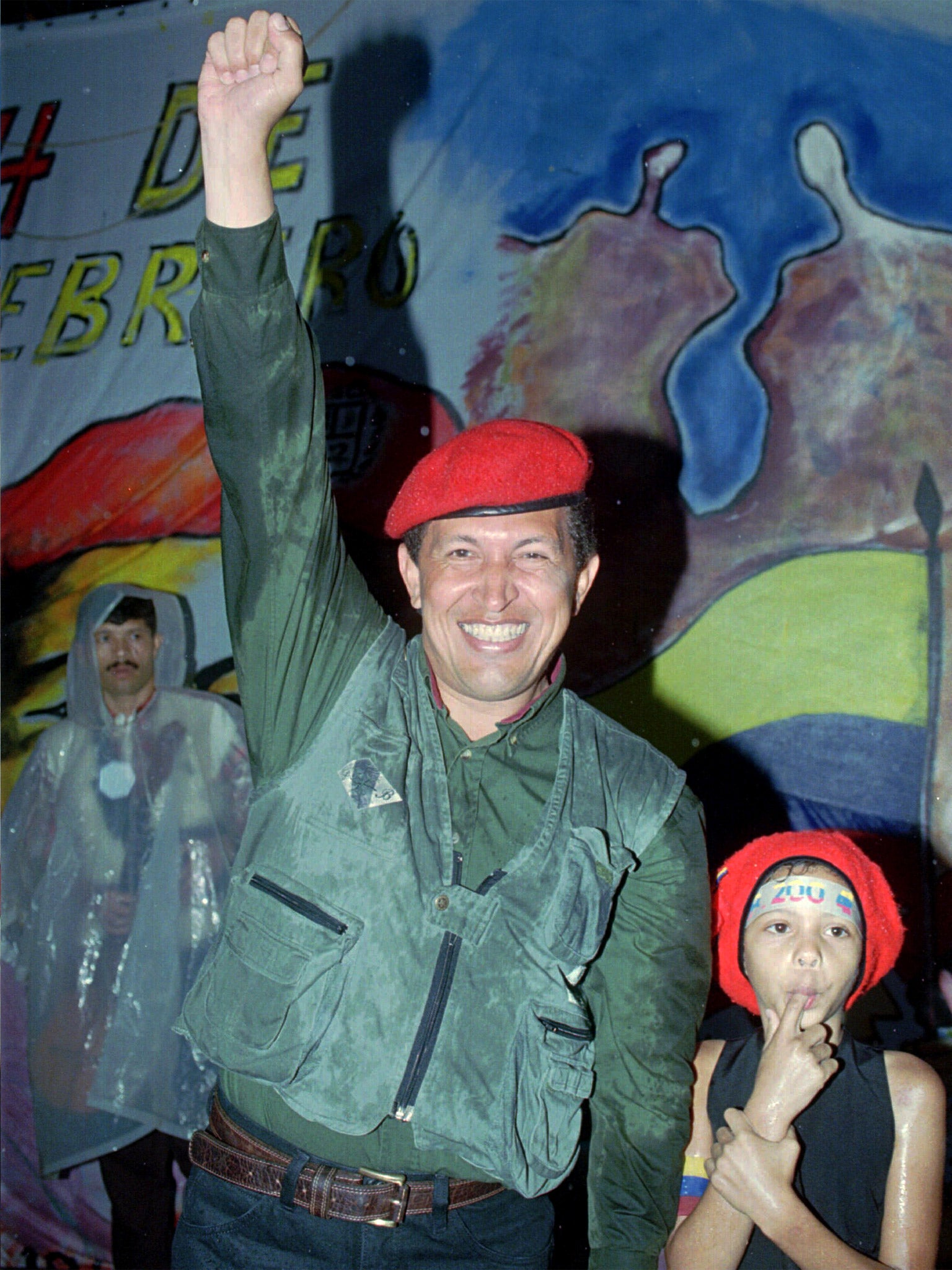

While in the military he developed his “Bolivarianism”, setting up a secret society within the army which he called the Movimiento Bolivariano Revolucionario 200 (MBR 200). He had risen to lieutenant-colonel, wearing the red beret of the paratroopers, when the Venezuelan capital Caracas exploded into a three-day frenzy of anti-government violence, with protests against the neoliberal, pro-market policies imposed by Carlos Andres Perez to satisfy the Internaional Monetary Fund. It started in the slums but spread throughout the city and the entire country, leaving hundreds, possibly even into the thousands of people dead, mostly at the hands of the security forces. It became known as el Caracazo [The Big One in Caracas].

Later quoting Bolivar as saying a soldier should never fire his gun at his own people, Chavez said it was the Caracazo which pushed him towards leading the 1992 coup against Perez. The historian Marksman, his mistress at the time, helped him plot the coup, but after he dumped her immediately thereafter she turned against him. “He’s the kind of man that showers you with flowers and chocolates, serenades you with romantic songs and never forgets your birthday,” she said in 2006. “People say he is a violent man, but he never raised a hand or his voice to me.” She said they dreamed together of “a prosperous Venezuela where justice would reign.”

Now, however, she went on, “You can’t trust him. He is imposing a fascist dictatorship. A totalitarian regime is coming because he doesn’t believe in democratic institutions. Hugo controls all the powers. He disguised himself as Little Red Riding Hood and turned out to be the wolf.”

After officers loyal to Perez gained the upper hand during the 1992 coup attempt, Chavez went on live national television to tell his men to surrender “for now”. The significance of those two words was lost on no one and Chavez instantly became something of a folk hero, especially to the poor and those who shared his part-indigenous facial features. He and his co-conspirators were court-martialed and sent to Yare prison, 35 miles from Caracas, where he could be seen talking to a bust of Bolivar in a private yard outside his cell.

Vindicated when President Perez was convicted of corruption, Chavez was pardoned by the new President, Rafael Caldera, in 1994. He immediately turned his MBR 200 base into a civilian political party, the Fifth Republican Movement (with the Spanish initials MVR), for which he ran for president in 1998. He won easily, leapt on to the world stage and remained there until his death. After being re-elected in 2006 he founded a new party, the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV). A lifelong coffee addict, he cut down from 26 cups of espresso a day when he took power, to a mere 13.

He married a journalist, Marisabel Rodriguez, in 1997, making her Venezuela’s First Lady, but they divorced in 2004 and the presidential palace thereafter was left without a feminine touch – at least a permanent one. “He could be in there with three women, or being totally celibate,” according to one Venezuelan journalist. “Nobody ever really knew.”

Chavez was diagnosed with cancer in the pelvic region in June 2011 and, after various treatments in Cuba and regular visits from his friend Castro, underwent surgery there on 11 December 2012. He had not emerged in public since then. Hugo Chavez is survived by his son Hugo, three daughters Rosa, Maria and Rosines, both his parents and several siblings.

Phil Davison

Hugo Rafael Chavez Frias, soldier and politician: born Sabaleta, Venezuela 28 July 1954; married 1977 Nancy Colmenares (divorced 1995; one son, two daughters), 1997 Marisabel Rodriguez (divorced 2004; one daughter); died 5 March 2013.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies