J.G. Ballard: Writer whose dystopian visions helped shape our view of the modern world

For 30 years J.G. Ballard had many readers in many lands. For them, everything he published was news. But after Steven Spielberg based a good though not incandescent film on his autobiographical novel, Empire of the Sun (1984), Ballard became publicly newsworthy over large parts of the world that his words had never reached directly.

He became a sage and prophet, whose visions of the cost of living in the modern world were an integral part of our understanding of the shape of things to come. At least one English dictionary has accepted "Ballardian" as a term descriptive of the landscape of the late 20th century: bleak, rusted out, choked with Ozymandian relics of the space age now past, dystopian – a landscape which surreally embodies the psychopathologies of modern humanity.

That none of this was new in Ballard's understanding of the world, his readers already understood. With an unwavering intensity of gaze, he had been reworking and refining the same fixed array of intuitions and insights from as early as the publication of his first science-fiction story, Prima Belladonna, in 1956. That story, like much of his early work, did not find easy entry into the British literary world. Almost every tale he wrote for more than a decade first appeared in a small British science-fiction magazine called New Worlds, at a time when British SF was formally and culturally very conservative. Only 10 years later, under the mid-1960s editorship of Michael Moorcock, would New Worlds become the natural home of the kind of transgressive, experimental, intensely written "New Wave" fiction that Ballard had been producing for years.

His instinct from the first had been to apply the inward visions of surrealism and psychiatry to the outer worlds of science fiction and, by 1960 or so, he was already beginning to describe the Space Age as a last, doomed, phallocratic attempt, on the part of the Hollow Men of the West, to gain immortality. Ballard may not have coined the term "inner space", which became a New Worlds catchphrase – J.B. Priestley, in They Came from Inner Space (New Statesman, 1953) was the first to use the term conspicuously – but he seemed to have taken to heart Priestley's description of the science-fiction invasion of outer space as a series of moves, "undertaken in secret despair, in the wrong direction". His genius was, devastatingly and unrelentingly, to take J.B. Priestley at his word.

For Ballard, to gaze into inner space – the world within the skull – was to gaze upon the antic face of the world, upon a landscape governed by Thanatos and Eros, the two great world-shaping principles common to Freud and the Surrealists. His genius was in his ability to "actualise" these principles in his fiction, and to choose protagonists who might plausibly embody his convictions about our state. Ballard's lead characters are almost invariably middle-class professionals: affectless physicians, benumbed apparatchiks, deracinated engineers, the swelling mob of rootless death-fixated suburbanites who are (his recent novels claim) the real terrorists to come. Ballard's 21st century is a vision of gated communities occupied by potential suicides and real killers, glassy with disinterest but deadly: Thanatos Unbound.

James Graham Ballard was born of English parents in Shanghai, 10 years before the outbreak of the Second World War. He was raised in a surreal suburb, transferred to downtown Shanghai as war began, and interned in the Lunghua concentration camp by the Japanese occupiers from 1943 to 1945. It is these experiences which are transmuted into Empire of the Sun and which, that novel makes pretty clear, were fundamental to his understanding that the world could only be survived if one knew its nature. In one of the many interviews he gave after Spielberg made him world famous, he said of this time that: "The reassuring stage set that everyday reality in the suburban west presents to us is torn down; you see the ragged scaffolding, and then you see the truth beyond that..."

Ballard was a born exile. England, which would be his home for life, and where he was to set most of his fiction, came as a privileged refugee in 1946. Almost immediately he made the intoxicating discovery of Surrealism, paintings and writings which seemed to authenticate his own experiences (at one point he hoped to become a painter). From 1946 to 1949, he attended The Leys School in Cambridge, which reminded him of Lunghua Camp and, in 1949, he began to study psychiatric medicine at King's College, Cambridge. He left after two years without graduating, spending the next year at London University. In 1953 he joined the RAF, ending up in a base in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan: flat country, torn by bad weather.

By 1954 he was back in England, and married to Helen Matthews. Between 1957 and 1962, when he became a full-time writer, he was an assistant editor for a scientific journal, Chemistry and Industry. In 1960, the Ballard family moved into a semi-detached home in Shepperton, Surrey, a suburban enclave gradually to become surrounded by motorways and battered by the continual growth of Heathrow Airport. In 1964, during a family vacation in Spain, his wife died suddenly of pneumonia, and he raised their three children himself. He became very well off after the Spielberg film, but never moved. Perhaps there was no need to. If he had consciously wished to combine internal-exile status, along with intimate contact with a great megalopolis of the Western world whose heat death he was predicting, he could not have chosen a better coign of vantage than Shepperton.

In 1962 he published the first of four science-fiction novels – The Wind From Nowhere, The Drowned World (1962), The Burning World (1964; published in the UK as The Drought) and The Crystal World (1966) – which transfigure in turn each of the four classic humours (Air, Water, Fire, Earth) into science-fiction landscapes for the enacting of holocaust. The last three of these novels have become classics of the genre because of the mesmeric grip of their portrayals of terminal catastrophe, but also notorious for seeming almost supernaturally flattened of any normal emotion about the desecration of the planet. But the passion, and the shockingly deadpan hilarity, were there to be discovered; a powerful sense that to gaze unblinkingly at the world is an act of rage.

This soon became clearer. Some of the stories written in the highly transgressive decade after 1965, particularly those assembled in The Atrocity Exhibition (1970), are full-frontal assaults on the psychopathological roots of the fall of the West. The book was pulped before release by its first American publisher, though it was released in Britain without problems, and filmed in 2000 by Jonathan Weiss. One reason for the pulping was certainly the inclusion of Ballard's most notorious single story, Why I Want to Fuck Ronald Reagan (1968), a perfect marriage of rage and hilarity. In 1970, he put together, for the Arts Lab in North London, an exhibition he called "Crashed Cars", based on a story called Crash! from Atrocity, and an obvious teaser for his next novel, Crash (1973), perhaps his most radical assertion of the intimate exchanges in our psyches between Thanatos and Eros. David Cronenberg's 1997 film, Crash, comes close to capturing the novel's dangerous, dream-like allure.

By 1970, Jimmy Ballard had developed into a remarkably attractive figure. He was of medium stature, with swept-back receding hair, and a gaze that seemed both bland and impatient. He was bonhomous in a fashion that somehow suggested to his companions that he might not, in truth, be that easy to please. Without seeming to notice his effect on others, without ever claiming to do much other than work hard in Shepperton, he gave an impression of almost dangerous worldliness, as though he understood too much. Perhaps because he seemed physically denser than other people, they orbited him. He was charismatic. He gave audience. He loved in particular women – his second autobiographical novel, The Kindness of Women (1991), makes this abundantly and attractively clear – and for years after 1965, he was intensely involved with more than one partner. In the late 1960s, he met Claire Walsh, whom he refers to as his "partner for 40 years" in his last book, Miracles of Life (2008), a memoir composed, as he makes clear in its pages, during a remission from the prostate cancer that killed him.

After works such as Concrete Island (1974) and High Rise (1975), each as intense in its way as Crash, his next few titles gave the impression that he was beginning to exhaust the central innovative fire of rage and insight that made his first six or seven novels, and his 120 or so stories, a central achievement of English writing in his time. Most of his great stories are early, assembled in volumes such as The Four-Dimensional Nightmare (1963) or Vermilion Sands (New York, 1971), which is set in a melting-watch Dying Earth; and inserted into later retrospects such as Memories of the Space Age (US, 1988), which gathers stories about the death of Space that date back as far as 1962 (no wonder so many American SF readers distrusted him), or The Complete Short Stories (2001), which, though seriously incomplete, runs to more than 1,100 pages. At the end of this long run of unremitting work, the retroactive orienteering of Empire of the Sun only intensified a sense that his career had climaxed, that all his cards were now on the table.

It was remarkable, therefore, how long Ballard sustained a high level of creative endeavour in later decades. No one has seriously claimed that novels such as Cocaine Nights (1996), Super-Cannes (2000) or Kingdom Come (2006) achieve anything like the unstoppable horrific presence of the earlier masterpieces, but they convey an undiminished wisdom about the nature of our world.

The most complete unfolding of his later sense of things can probably be found in a quite astonishing book-length interview published by the magazine Research as the self-standing Research No 8/9 (1984) but he remained unfailingly eloquent until the end of his life, as the interviews assembled in Conversations (2005) attest. "At times", he said in 2004, "I look around the executive housing estates of the Thames Valley and feel that [a vicious and genuinely mindless neo-fascism] is already here, quietly waiting its day, and largely unknown to itself ... What is so disturbing about the 9/11 hijackers is that they had not spent the previous years squatting in the dust on some Afghan hillside ... These were highly educated engineers and architects who had spent years sitting around in shopping malls in Hamburg and London, drinking coffee and listening to the muzak."

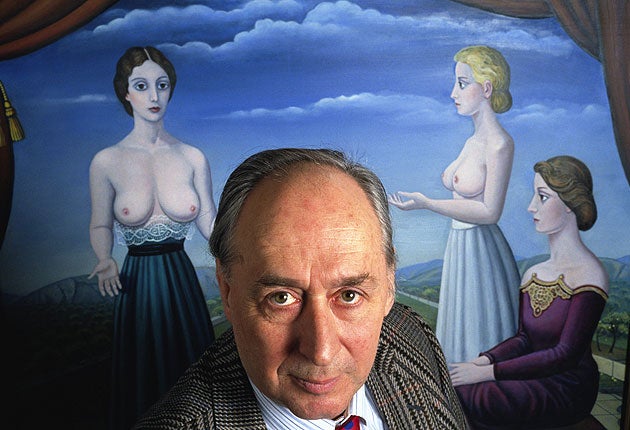

He continued to live in Shepperton. In 1985, he had a copy made of a lost Paul Delvaux painting – in truth, not a very good one – and kept it propped against the same wall in his work-room for the rest of his life. He refused an OBE in 2003, as the whole rackety world of gong-bestowing seemed to him a "Ruritanian charade" designed to "prop up" the Royals. He continued to act with dignity and insight the role of a public man of letters, publishing reviews and comments frequently – A User's Guide to the Millennium: Essays and Reviews (1996) assembles some of this work. Miracles of Life is a memoir of piercing clarity; a projected posthumous volume, Conversations with My Physician, may continue Ballard's engagement with the facts of his mortality.

His late novels never flinch from addressing the "elective psychopathy" that increasingly riddles the anaesthetised world we are now beginning to inhabit. It is a fate Ballard had been predicting for half a century. His fiction was perhaps too invariant for him to rank as the greatest literary figure of his generation but of all the writers of significance in the last decades of the 20th century, he was maybe the widest awake.

John Clute

James Graham Ballard, novelist and short story writer: born Shanghai 15 November 1930; married 1955 Helen Mary Matthews (died 1964, one son, two daughters); died London 19 April 2009.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments