John Plumb: Abstract painter showcased in the 1960 exhibition 'Situation'

If proof were needed that success can blight a painter's career, then the life of John Plumb would provide it in spades. Plumb scored his first triumph as an artist 60 years ago when a portrait of his future wife, Joan Lawrence, was chosen for exhibition at the New English Art Club. The 21-year-old painter was then still a student at the Byam Shaw School of Art in London; a decade later, he was having solo shows at the trend-setting Gallery One in London. In September 1960, Plumb's fame peaked with his inclusion in the Royal Society of British Artists' exhibition "Situation".

A defining moment in contemporary art on a par with Damien Hirst's 1988 show "Freeze", "Situation" brought a generation of British abstract painters to the public eye. Among the 20 artists in the show were such soon-to-be-big names as William Turnbull, John Hoyland and Bridget Riley. So, too, was John Plumb, whose name has been largely consigned to footnotes.

The reason for this is in part historical. No sooner had the "Situation" painters established themselves in the British mind than the art market was swept by the vagaries of Pop. The 1970s were not a good time for abstractionists, and Plumb was among many artists who found the sudden eclipse of their style hard to take. Born and raised in the car-making town of Luton, he had served an apprenticeship as an auto-stylist trainee at Vauxhall Motors. This pragmatic pedigree informed both his own work and his approach to art-making in general. (At the height of his success in 1964, Plumb took time out of the studio to design a fabric, "Chiricahna", for Heal's department store.)

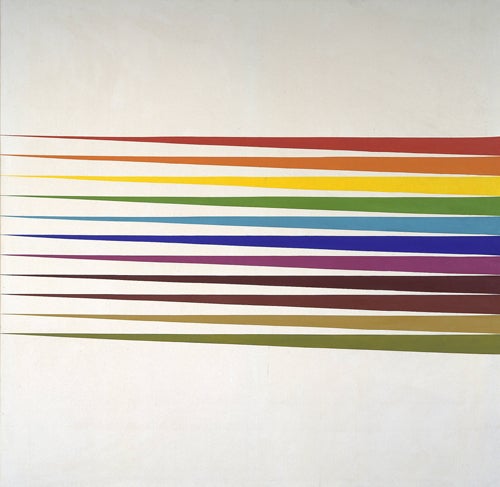

Pictures such as Edgehill (1963), shown in "Situation" and now in the Tate collection, have an engineered feel to them, their stripes of colour being rendered in industrial PVC duct tape. Highly experimental and often very beautiful, Plumb's works of this period are rooted in real life in a way that Riley's more rarefied explorations of space and perception are not. The critic Lawrence Alloway praised works such as Edgehill for their "tough, lyrical colour sense" and "dimensionality". They have a studied male-ness that looks to the macho ethic of early American Abstract Expressionists, a quality that would not suit them for survival in the fey world of Pop.

As a result of all this, Plumb went through a crisis of artistic identity that was reflected in a constant change of style. In the late 1960s, his canvases veered between large, colour field works and others that tried to find a more refined vocabulary of geometric abstraction. Echoing Bridget Riley, Plumb experimented with using assistants to apply his acrylic for him, and allowed the various forms in his paintings to generate themselves. The sterility of this hands-off approach soon palled, however, and he moved back to a more gutsy, improvisational way of working. His inability to find a consistent voice was echoed in a certain fickleness with dealers: at various times, Plumb was represented by Gallery One, Axiom and the Marlborough, although he didn't survive for long with any of them.

At something of a personal nadir in 1969, he was appointed senior lecturer in painting at the Central School of Art, where he had also been a student. Plumb continued in this post for 13 years, throwing himself into his teaching with a single-mindedness that inspired his students but left little time for his own work. Taking early retirement in 1982, he began to paint again, although with characteristic perversity the pictures he now made were naturalistic landscapes of the area around his home in Shepperton, often done in pastel. A self-portrait of this period, Camden Town-ish in feel, suggests that this new departure was less a homecoming than an act of despair. Showing a bearded Plumb in a flat cap and half-moon glasses, it includes the self-denying object – a clock without a face – which gives the work its name.

It took a move to Yarnscombe in Devon in 1993 to give Plumb the space and confidence to go back to abstraction. That this move coincided with the onset of the macular degeneration which would rob him of his sight may have helped push him away from figuration. A lifelong devotee of jazz, Plumb took up improvising again, the works he made in Yarnscombe being as much to do with touch as with sight. His Hydrastructure: What Is It? (1992) – the title is taken from a jazz riff by Miles Davis – follows Klee's lead in taking a line for a walk. You sense the push of the paint, the touch of the hand. Plumb's last works have a feel of the American abstractionist Brice Marden, although their worm-like lines are more visceral than Marden's. They make a worthy end to a career that peaked too early.

Charles Darwent

John Plumb, painter: born Luton, Bedfordshire 6 February 1927; Senior Lecturer in Painting, Central School of Art and Design 1969-82; married 1951 Joan Lawrence; died Yarnscombe, Devon 6 April 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments