John Reed: Comic lead of the D'Oyly Carte

Many Gilbert & Sullivan fans regarded John Reed, comic lead of the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company for 20 years from 1959 to 1979, as absolutely the best there had ever been in the baritone patter-song roles. Yet when he went to Glasgow to audition for the company in 1951 it was as "an experiment". As a boy he had studied elocution, dancing, singing and mime, but he worked in builders' and insurance offices, and during the war as a tool fitter and instrument maker, before playing musical comedy parts for the Darlington Operatic Society, and taking to the stage as an actor in repertory theatre at Stockton, Redcar and Saltburn.

At the time of his audition he was not a G&S enthusiast, and in the evening after his Glasgow audition it was not the D'Oyly Carte he went to see perform but the ballet, "which was my first love anyway". Recalled for a second audition a fortnight later in front of the company's proprietor, Bridget D'Oyly Carte, and the general manager, Frederic Lloyd, this time in Edinburgh, he was astonished to be offered a job as soon as he could start.

He joined the company at their next stop, Newcastle, as a chorister and understudy to Peter Pratt, then the principal comic baritone, who was endowed with a much heftier operatic voice than the light but pleasing baritone Reed possessed. Reed's own solo parts at this time were mostly minor roles like the Major in Patience, a part traditionally performed by the comic lead's understudy. As Antonio in The Gondoliers he made use of his training and skill as a dancer, footing it nimbly and vigorously while singing "For the merriest fellows are we". By 1955 he was undertaking the patter role of the Learned Judge – "and a good Judge too" – in Trial By Jury.

From the outset Reed refused to watch performances from the wings. "I only saw the principal I was understudying when I was on stage with him," he said, "because I wanted to be sure that when I came to do the role it would be my thing and not his."

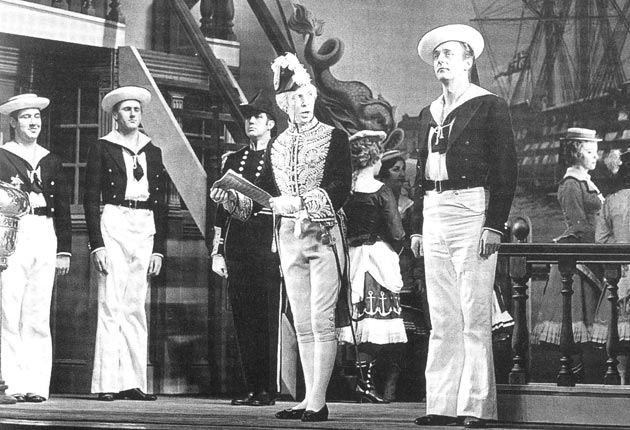

When in the spring of 1959 Pratt fell ill, Reed came into his own and "it was suddenly two or three first nights one after another". Later that year Pratt abruptly left the company, and Reed succeeded to all the major roles: Bunthorne in Patience, Sir Joseph Porter in HMS Pinafore, Major General Stanley in The Pirates of Penzance, Ko-Ko in The Mikado, the Duke of Plaza-Toro in The Gondoliers, John Wellington Wells in The Sorcerer, the Lord Chancellor in Iolanthe, Robin Oakapple in Ruddigore, Jack Point in The Yeomen of the Guard and King Gama in Princess Ida.

Reed said that of all his Gilbert and Sullivan roles the one he probably liked, and developed, best was Ko-Ko: "Ko-Ko is almost me. There's a lot of me in the character. It lets me bring out my own sense of humour." But the one he identified with most closely was Jack Point in The Yeomen of the Guard, who, he was convinced, died of a broken heart (the stage direction says only that Jack "falls senseless").

"That really is me," he said. "Jack Point is me in another age – just a strolling player. I really believe I could die of a broken heart, and after the final scene I don't want Jack to stand up for the curtain calls". Reed wanted Jack, instead, to be borne Hamlet-like from the stage (a conceit producers were reluctant to indulge), acknowledging: "Every comedian wants to know they have the ability to make people cry as well as laugh."

The bits of business and topical interpolations he invented in his encores to provoke additional laughter were notorious. As Sir Joseph Porter ("Ruler of the Queen's Navee") he had the character during the encores to the Act II trio desperately signalling for assistance in semaphore. Then, without telling anyone what he intended, he hired and hid a lifebelt on set, and, holding his nose, jumped overboard. This so shocked the determinedly traditionalist conductor, Isidore Godfrey, that the first time he did it Godfrey fell off his podium.

Reed invested all his parts with inventive wit, subtle expression and great comic timing. He was not, he admitted, the greatest of singers, the best of dancers or the most gifted of actors, but he reckoned to make the most of what he had got to maximise the audience's enjoyment. "It's the accumulation that counts," he said, "the sum of all the parts."

He regretted not being given the chance to play the Mikado, traditionally reserved for bigger men. "I could do it. I could be imperious and terrifying," he insisted. "After all, the Japanese aren't a big race, are they?"

For what he regarded as his toughest role, J.W. Wells in The Sorcerer, he was required to act in cockney, a far remove from his native northern accent. He managed it to great comic effect, but did not attempt to carry cockney into the breathtakingly fast patter songs for which accuracy of enunciation was essential.

His least favourite role was probably the hunch-backed and monstrous King Gama in Princess Ida, for whom he felt rather sorry. His principal objection to the part, though, was the heavy make-up that hid every feature of his face except his eyes, and made it impossible for him to wear his glasses so that he could do his newspaper crossword while waiting to go on.

The D'Oyly Carte's 1975 centenary season brought him the opportunity to tackle two more roles, Scaphio in Utopia, Limited and Grand Duke Rudolph in The Grand Duke, works which were revived that year for the first time since their original productions in the 1890s.

During his time with the company Reed undertook 11 overseas tours, 10 as principal comedian. He always claimed that the company was one big family. For a time it was "the Bag family" with many of the members and staff being given "bag" nicknames, so that Reed was "Gasbag", his leading lady "Old Bag", the wardrobe mistress "Laundry Bag", the jobbing understudy "Carrier Bag" and so on. But when abroad, Reed conceded, he had to play the star and be available for interviews and photography, making the tours even more exhausting.

Off-stage, Reed insisted, he was a shy and private person, hiding behind the crossword in a corner when eating alone in restaurants, and often driving long distances from provincial theatres to spend time in his own flat.

Reed left D'Oyly Carte in 1979. He worked in specially created shows and Gilbert and Sullivan performances in Britain and America, but returned as guest artist with D'Oyly Carte several times after his retirement. He took part in the company's "last night" performance when it succumbed to economic pressures and closed in 1982.

After retirement Reed moved to Halifax, where he directed local amateur performances by the West Yorkshire Savoyards and others, and productions at the International Gilbert and Sullivan Festival in Buxton, Derbyshire, as recently as 2004.

Robin Young

John Lamb Reed, actor and comic baritone: born Close House, near Bishop Auckland 13 February 1916; OBE 1977; partner to Nicholas Kerri; died Halifax 13 February 2010.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies