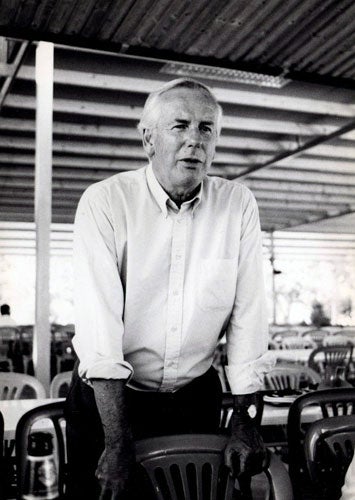

Jonathan Bates: Award-winning sound editor who became closely associated with the films of Lord Attenborough

Jonathan Bates was a brilliant sound editor who won two Bafta awards and an Oscar nomination for his outstanding contributions to cinema. He enjoyed a particularly rewarding association, and friendship, with Richard Attenborough, for whom he supervised the sound on 10 films, including Gandhi (1982), which earned him his Oscar nomination.

The contribution of sound to a film's success is easy to underestimate. "If you notice it, then it has not been done well," said the film editor Leslie Walker, another Bates champion. "He was the best sound editor in this country, a great technician who had artistic flair, something that's missing these days. He cared about fine detail: a V bomber, for example, had to be the right one, not any V bomber. I remember that when we did Mona Lisa (1986), in which Bob Hoskins played chauffeur to a call-girl, Jonathan walked around areas of London with a tape recorder stuffed up his jacket in order to capture the authentic sounds of call-girls."

On completion of post-production work on Roman Polanski's Macbeth (1971), Polanski enthused over Bates's work. "The pigs were prodigious, arrows impressive, footsteps fantastic, sword clashes sensational and post-synching beyond belief," he said.

The son of the novelist H.E. Bates, Jonathan had a childhood he later described as idyllic in the small village of Little Chart in Kent, where he was born in 1939, the youngest of four children. H.E. Bates and his wife, Madge, had converted a disused Granary in Little Chart into a beautiful rustic home and led lives "not dissimilar," said Jonathan's son, Timothy, "to the lives of the family in H.E. Bates's later books about the Larkins, such as The Darling Buds of May."

Educated at King's School in Canterbury, Bates became fascinated by aeronautics, and his first ambition was to be a pilot. However, the people who came into his life through their connections with his father soon helped to change his mind. The director David Lean, who had bought the rights to H.E. Bates's novel Fair Stood the Wind for France for possible filming, even suggested that had he met Jonathan sooner he would have cast the boy (who was rather skinny) in the title role of Oliver Twist. H.E. Bates later wrote the final screenplay for Lean's Summertime (1955), transforming Arthur Laurents' flawed play The Time of the Cuckoo into a romantic masterpiece.

By the time Jonathan left school the following year, he had determined to work in films, and his father, who had earlier scripted The Loves of Joanna Godden (1947) for Ealing Studios, asked the studio head, Michael Balcon, to take on Bates as a runner. Bates later recalled that among his first tasks was making tea for Alec Guinness on the set of Charles Frend's Barnacle Bill (1957), the last Ealing comedy.

Graduating to assistant in thecutting rooms, Bates became known to editors and directors, and credited his first mentor as the late Gordon Stone, who had been dubbing editor on such classics as Passport to Pimlico and Kind Hearts and Coronets (both 1949), and sound editor on The Ladykillers (1955). When Ealing closed in 1959, Stone hired Bates as an assistant dubbing editor on the Disney production Kidnapped (1960), the first of several Disney films on which Bates worked with him.

Bryan Forbes's poignant drama of childhood innocence, Whistle Down the Wind (1961), on which Bates was an assistant, proved to be a key film in his life and career. The film was produced by Richard Attenborough, who was to hire Bates as sound editor on the majority of his films, and working as an assistant dubbing editor was Jennifer Thompson, who later became Bates' wife. The following year, Bates received his first screen credit as sound editor, on Seth Holt's desert melodrama Station Six Sahara, but the film that consolidated his reputation was Ken Annakin's comedy about the early days of aviation, Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines (1965), which was to become one of Bates' favourite films, combining his love of aeroplanes with his new career.

When Gordon Stone died midway through filming, Anne Coates was brought in as film editor, and she recalled that at first there was some resentment from the crew and she felt an outsider. "But Jonathan was wonderful," she said, "very friendly and he couldn't have been more helpful."

The following year, while Coates and Bates were working in Paris on the farce Hotel Paradiso, Bates and Jennifer Thompson were married. Shooting was then disrupted when the French producers insisted that Bates be replaced by a French sound editor, to which the director Peter Glenville responded by moving post-production back to the UK.

Bates and Coates worked again together on Murder on the Orient Express (1974). "Jonathan did such a wonderful job with all those old trains," said Coates, "meticulously recreating every little sound perfectly. The director, Sidney Lumet, thought he did a superb job."

Mick Monks, an assistant on the film, said: "There was a lot of looping to be done after the film was shot because when you have a group of actors in period dress filming on location, you can't reshoot every time the dialogue is drowned by aircraft overhead or whatever. I remember seeing this group of international stars, including Ingrid Bergman, Wendy Hiller, Sean Connery and John Gielgud, lining up to go into the recording studio to re-record their dialogue with Jonathan, and Lauren Bacall asking nervously, 'what's he like?' Jonathan, of course, charmed them all."

Monks, a great friend of Bates, shared his passion for cricket. "We would go to Lords and picnic, as you could back then," he said. "We'd eat pork pies and Jonathan would always bring the claret. We also both played for the Twickenham All-Stars."

From the mid-Sixties on, Bates was rarely without work, with films such as Where Eagles Dare (1968), Dracula (1979), A Fish Called Wanda (1988), Shirley Valentine (1989) and the Attenborough films, including A Chorus Line (1985). "As it was about dancers, the sound of footsteps was very important for different types of shoes," the film's editor John Bloom said. "Jonathan was always prepared, and had quality sound and synchronisation ready for the director. Re-recording is very expensive and he was always prepared with alternatives."

Other Attenborough films included Cry Freedom (1987), for which Bates won a Bafta Award, Chaplin (1992) and Shadowlands (1993). Bates' Oscar nomination was for Attenborough's Gandhi, which was nominated for nine Oscars, and won eight, with Bates the unlucky loser to ET.

In 2003, Bates decided to retire and enjoy his garden and his grandchildren, but he did one more film, Closing the Ring (2007) as a favour to Attenborough. When Leslie Walker, who had never done a musical before, asked him to join her on Mamma Mia! (2008), he declined (to the chagrin of his grandchildren), but after being diagnosed with a brain tumour in June he made a point of seeing the film in his wheelchair.

Tom Vallance

Any director working in British cinema over the past four decades would move heaven and earth to secure the services of Jonathan Bates when it came to dubbing, writes Lord Attenborough. I was in that lucky situation with Young Winston, the second film I directed, in 1972. Possessed of an expertise beyond compare, Jonty went on to become Supervising Sound Editor on every one of my subsequent productions.

Again and again, sequences which had seemed to work quite satisfactorily in isolation would be immeasurably enhanced by some subtle or unexpected addition to the soundtrack which was his contribution and his alone. Pressure is ever-present during this phase of film making. I can, however, recall no occasion on which Jonty ever gave vent to irritation or frustration. He was unquestionably the most unruffled of men; kind, thoughtful, generous and considerate.

He will be greatly missed by all his film industry colleagues and, for me, the loss of his friendship and loyalty creates a chasm beyond compare.

Jonathan Bates, film sound editor: born Little Chart, Kent 1 November 1939; married 1966 Jennifer Thompson (one son, one daughter); died Esher, Surrey 31 October 2008.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies