Manny Steward became the best trainer of his generation after an anonymous apprenticeship travelling to fights with young boxers packed in his car, a cooking stove in the trunk and the local US state rulebook in his pocket. He was a master tactician who understood the crazy hearts of the fighters he shaped, guided and often created from scratch. He had an ability in the gym, a hotel room in the lonely hours before a fight, the dressing room and the ring during a fight to communicate clearly a strategy for victory. He could whisper and he could growl.

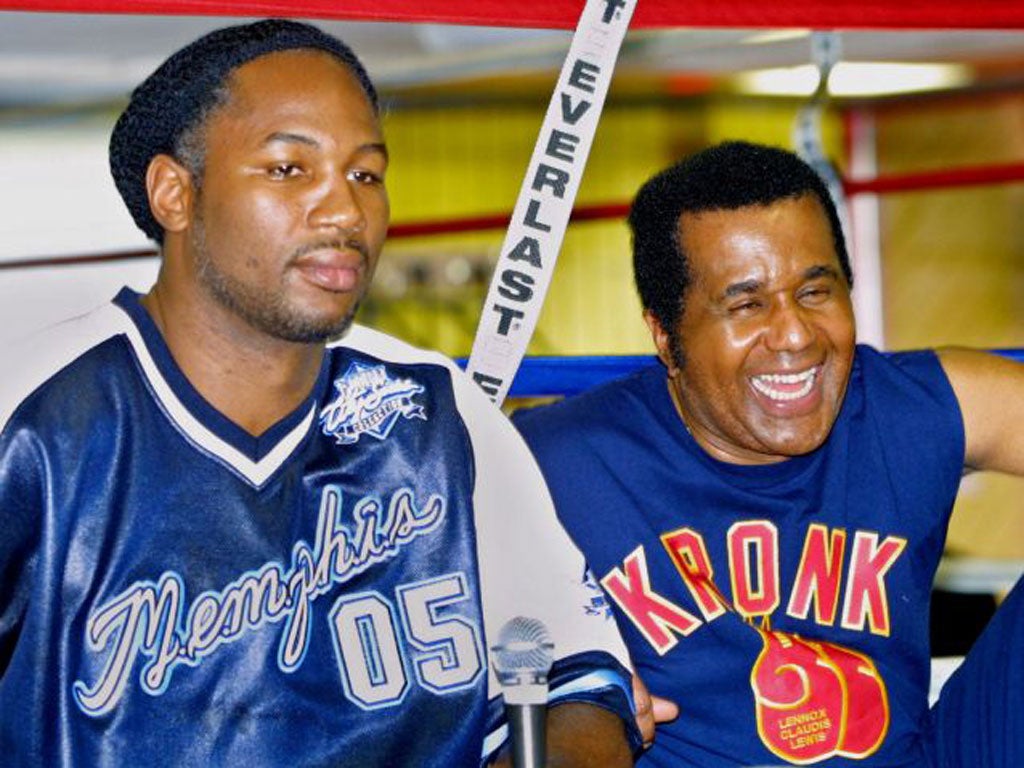

He is now acknowledged as one of boxing’s greatest trainers, having worked with over 40 proper world champions during a career that started in 1969 when he walked into the Kronk, a forgettable boxing gym in a basement in one of Detroit’s many shell-shocked districts. He had turned his back on boxing after winning the 1964 National Golden Gloves bantamweight title, and qualified as an electrician in Detroit. The city had been his home since he and his mother had moved there from West Virginia when he was 11, and he had begun to box at the Brewster Centre, where Joe Louis, also a southern migrant, had boxed 30 years earlier.

In 1970, Steward accepted the role of part-time coach at the Kronk Gym for $35 a week. In 1971 he had a full team of boxers entered in the local Golden Gloves event and by March 1972, when he was earning $500 a week with the Detroit Edison electrical company, he quit that job to train amateur boxers full-time: “It was my dream to make an amateur team famous.” Steward sold cosmetics and insurance door-to-door so that he could keep his dream alive and the Kronk sweatbox open. “We were all fighting for our lives back then – me to survive and the boxers to be the best that they could be,” he said. “Nobody had it easy and that makes boxers special.”

In 1977, when he finally received some financial support for his endless hours in the Kronk from wealthy backers, Steward turned professional trainer with Tommy “The Hitman” Hearns. This made the Kronk name and was the start of boxing’s most extraordinary partnership. Hearns had walked through the door at the Kronk in 1970, a skinny boy of 11. “His trunks were falling down and he was so scrawny,” Steward remembered. They won and lost world titles and were central figures, with Roberto Duran, Marvin Hagler and Sugar Ray Leonard in some of boxing’s most memorable and lucrative championship fights.

Steward influenced hundreds of other boxers from the early 1970s, though not all went on to make millions and enjoy the riches that Hearns deserved. The Kronk was in a desperate part of Detroit and some of its best fighters went back to the streets; Steward, despite his gentle voice and smile, had always been familiar with those streets. “I lost a lot of great boxers over the years,” he admitted.

The Kronk was volatile, packed with fringe characters; before the first Hearns and Leonard fight an incident by the pool at Caesars in Las Vegas perfectly captured the menace hidden behind the gym doors. Some of “Tommy’s good friends” were by the pool cleaning their guns when one went off. Nobody was hurt but the “friends” had to hand in their firearms. The affable Steward of recent years, the HBO face of boxing, was a different beast to the man that made the Kronk. As the veteran American boxing writer George Kimball once said: “Nobody could say ‘motherfucker’ quite like Manny.”

Steward took control of careers, turning good fighters into giants and salvaging lost causes with his tactics, methods and words. Lennox Lewis owed him a debt, so did Wladimir Klitschko; both heavyweights are what they are because of Steward. “I wish I could have been there for him, like he was for me,” said Lewis. Steward’s brutal manhandling of Lewis in the corner during the Mike Tyson fight was crucial. “You have to bully a bully,” was a Steward war cries.

Steward was a boxing man of the oldest old school. He was equally happy training legends in epic fights, or putting electrical tape on the doors and windows in a motel bathroom to create a steamroom to help a kid of 115 pounds lose two pounds for a tournament in the middle of nowhere. “I taught boxing – few teach boxing now,” he said “Boxers today want to be businessmen and are not interested in becoming good prizefighters.”

He died in hospital following complications after stomach surgery. “He went off fighting like Hearns and Hagler,” said his sister, Diane Steward-Jones. Hearns v Hagler may have been the greatest fight of all time and Steward, who was in the corner on the night, deserves the comparison.

Steve Bunce

Emmanuel Steward, boxing trainer: born Bottom Creek, West Virginia 7 July 1944; married 1964 Marie Steel (two daughters); died Chicago 25 October 2012.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies