Marc Rich: Businessman who was named on the FBI’s ‘Most Wanted Fugitive’ list

He arranged 78 shipments of oil to the apartheid regime of South Africa, breaking the UN embargo

Marc Rich was one of the world’s most influential commodity traders, a veritable godfather of the business, whose former colleagues now run two of the world’s largest trading firms, Glencore and Trafigura. His business philosophy – he once told an interviewer “you can’t run a business on sympathies otherwise you’d be hampered” – was worthy of a villain in the works of Ian Fleming or Eric Ambler.

He specialised in dealing with outcast countries, selling oil to everyone from Pinochet and the Sandinistas in Nicaragua to apartheid-era South Africa, ensuring that for years his name appeared on the FBI’s Most Wanted Fugitives list. Yet he was pardoned by President Clinton just before he left the White House and died, untouched by the law, in the Villa Rosa, a huge, cream-coloured mansion overlooking Lake Lucerne.

He was born Marcell Reich in Antwerp in 1934. In the early 1940s, like thousands of other Jews, the family fled to America to escape the Nazis, settling in Kansas City, where they opened a jewellery store. From the beginning, Rich was different. His preferred languages were French, German and Yiddish, and at school he aimed to attract as little attention as possible. People who worked with him said that before making any decision he always weighed the risks carefully and that his obsession with secrecy knew no bounds – “Marc gave paranoia a bad name,” said one business associate.

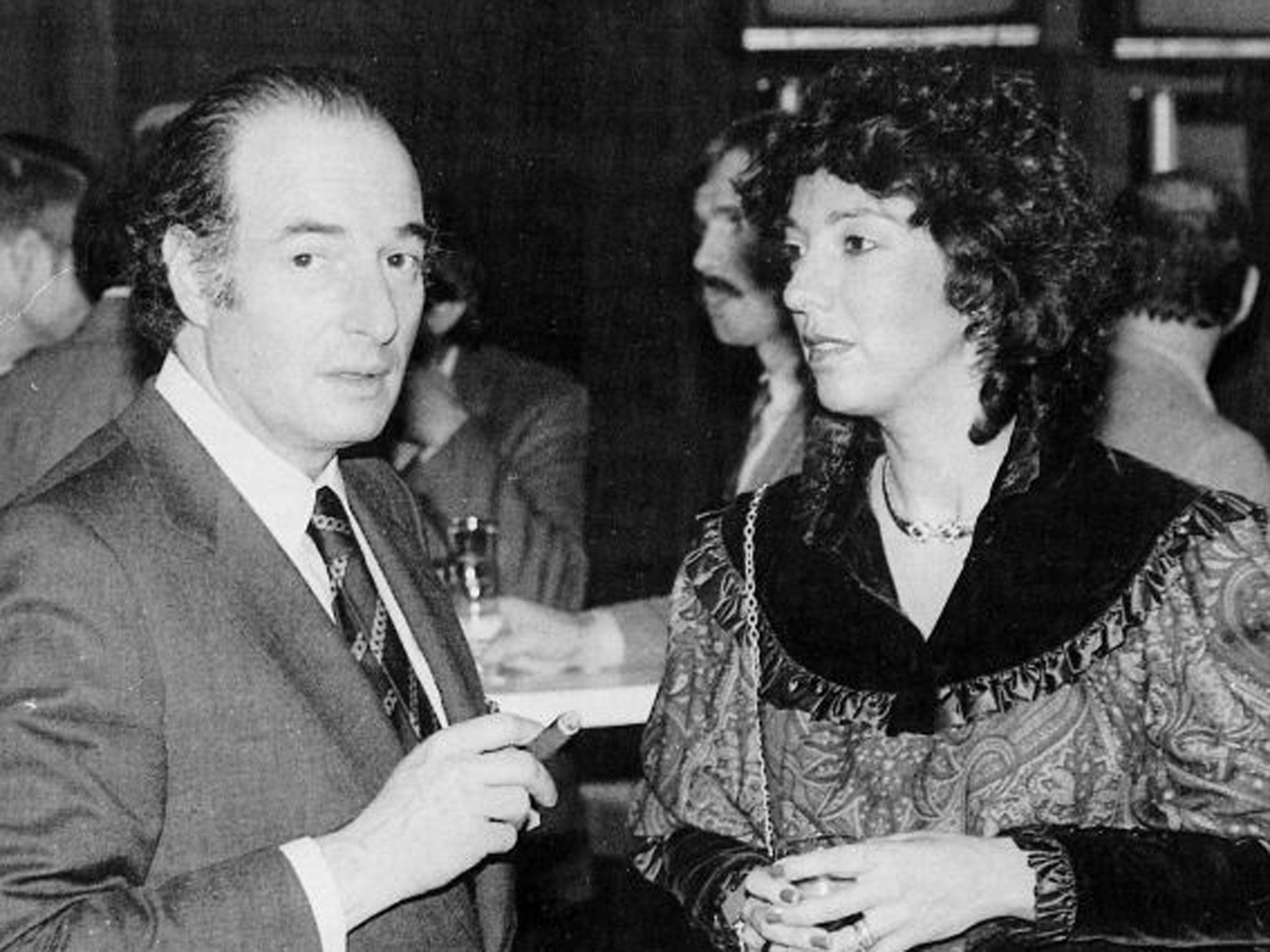

Rich’s career as a deal-maker began in 1954 when he joined Phibro, then the world’s largest raw-materials trading company. From the start he stood apart, if only because of the risks he was prepared to take. By 1966 he was successful enough to marry Denise Joy Eisenberg, a beautiful brunette whose parents, like his, had fled the Nazis. Her father, Emil, was one of the largest shoe manufacturers in the US.

Rich’s big opportunity came in 1973 with rumours that Opec was about to impose an oil embargo. Rich and a colleague, Pincus Green, bought $150m worth of crude oil at $5 above the going rate – the “spot rate”. In the late 1960s he had taken on the so-called “Seven Sisters”, the companies that controlled the world’s oil business and thus invented the spot market for oil. When news of the scale of the deal reached head office, Phillipp Brothers’ board panicked and forced Rich to sell.

But he had been right, and a few months later, when the oil price soared, the board gave Rich a freer hand. A year later when the board refused to pay them the bonuses they thought they were due, he and Green left and set up their own business in Zug, a Swiss canton known for its corporate secrecy and low tax rates, at 10 per cent a mere quarter of that in the US.

The 1970s were good for Rich as he expanded the previously undeveloped oil trade. Exploiting his contacts with the Shah’s courtiers he bought Iranian oil for $15 a barrel and then sold it at far above that figure. By 1976 his pre-tax profits were $367 million. He built what was named “the Dallas building” – a glass tower block in Zug – to house his oil and commodities trading operation, making him appear to Zugites like their very own JR Ewing.

Rich saw no reason to stop dealing with Iran when Ayatollah Khomeni replaced the Shah. But clients like him, Pinochet’s Chile and Ceausescu’s Romania were just the tip of the iceberg. Between 1979 and 1988 he also arranged 78 secret shipments of oil to South Africa, in an obvious breach of the UN embargo against the apartheid regime, disguising the deliveries by filing false shipping reports. By then he was dealing on an awesome scale. In the early 1980s he cornered 40 per cent of the world aluminium market and then, seemingly by accident, the world silver market, too; he bought a 50 per cent share in 20th Century Fox as a tax write-off and managed to keep it secret for six whole months, selling it at a profit to Rupert Murdoch.

According to the 1983 US indictment he illegally bought millions of barrels of oil from Iran during the US hostage crisis in 1979-80 in contravention of the US ban on trading with the enemy. In 1984 he settled wrote the government a cheque for $170m to compensate for tax violations and contempt of court for refusing to surrender subpoenaed documents.

But he was still guilty of trading with the enemy, and he and Denise still could not leave Switzerland without fear of arrest except to go to Spain, where Rich had a villa in Marbella, and Israel, countries in which Rich had taken out citizenship. He had endeared himself to the Swiss through his charitable foundations, donating money to the Zurich opera house, Lucerne’s culture centre and Zug’s modern art museum, and sponsoring the local ice hockey team.

By then the stories – not necessarily accurate – had accumulated: how en route from Switzerland to Finland he had to order his jet to reverse course at 20,000ft to avoid being arrested by the FBI at Helsinki airport; the tunnel he built between the “Dallas building” and the Glashof restaurant opposite so he could slip out to lunch without fear of assassination; or the time he was allegedly held hostage in Azerbaijan while his captors considered whether to sell him to the Russians (who were allegedly fed up with him for getting hold of their reserves of gold and other precious metals); or the rumours that he had slipped in and out of Britain and the US many times under false passports.

In 1996 he and Denise had gone through a bitter divorce but four years later Denise wrote to President Clinton in support of her husband’s application for the controversial presidential pardon he granted Rich on his last day in office despite the misgivings of law enforcement officials. They had barely exchanged a civil word in five years, but as she told one interviewer, “All I thought at the time was, ‘OK, he’s the father of my children, and if that’s what they’ve asked me to do, I’ll do it’.” Probably more relevant were the efforts of Jack Quinn, a former White House counsel, and other senior officials, and a deal with the Israelis, for whom he had found supplies of oil during a crisis in the mid-1970s.

Through a mysterious intermediary, a former Mossad agent, Avner Azulay, Rich managed to exert pressure on Clinton from prominent Israeli politicians including Ehud Barak and former prime minister Shimon Peres. But by then Rich was far less influential than he had been. In 1993 an ill-advised attempt to corner the world zinc market brought him apparently to the edge of bankruptcy, and he sold his business to associates, who renamed it Glencore. He then set up a smaller business which he sold, again to associates, in 2003, living for 10 years in retirement surrounded by a major art collection; he was particularly fond of the works of Picasso.

Marcell David Reich (Marc Rich), businessman: born Antwerp 18 December 1934; married Denise Joy Eisenberg (marriage dissolved); died 26 June 2013.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments