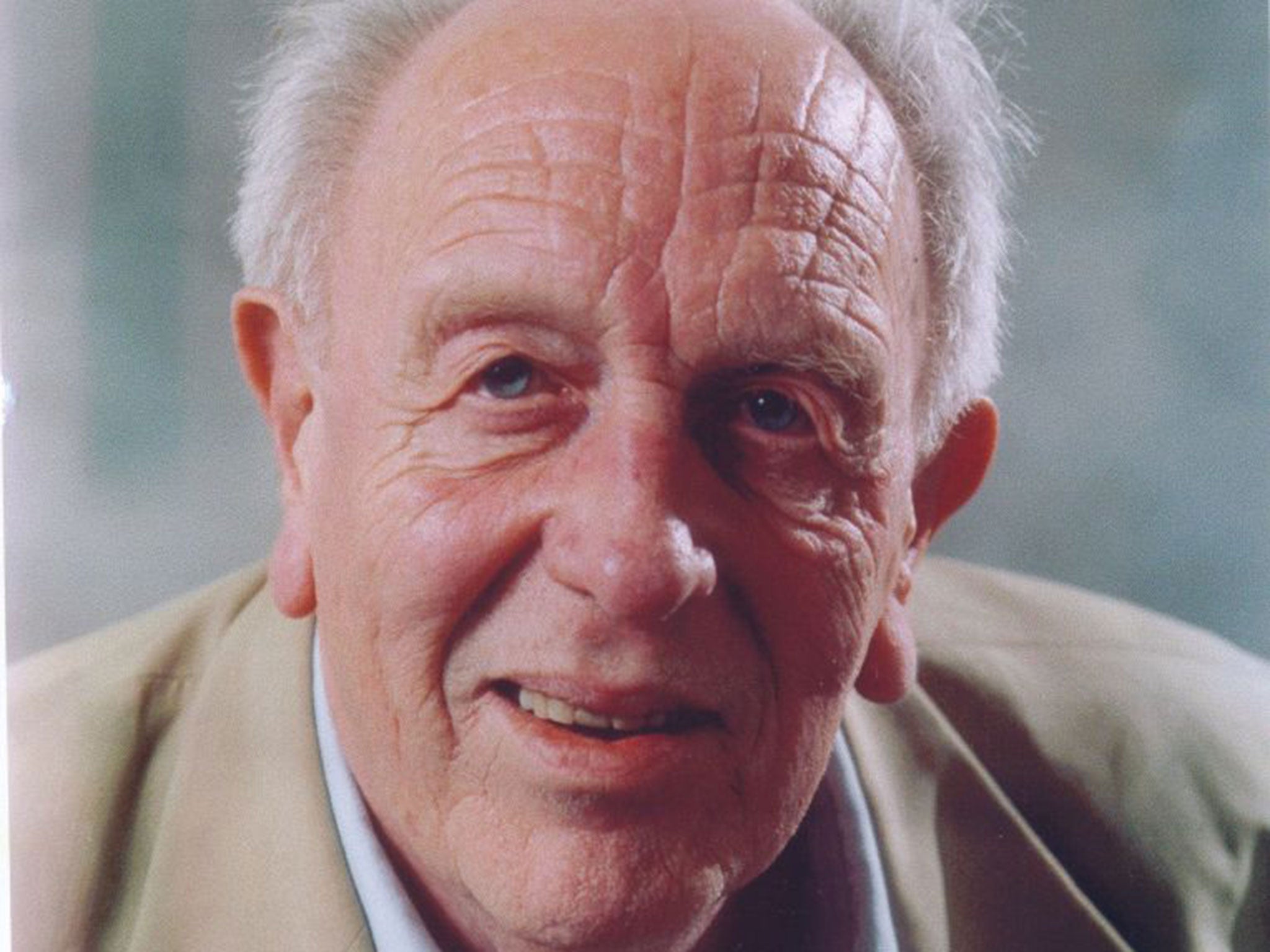

Nigel Calder: Prolific journalist and author who did much to educate the public in the understanding of science

He was a key figure in the creation of a highly successful British weekly science magazine. He was a prolific author who published almost 40 popular books. But most of all he educated, excited and inspired countless millions of television viewers, taking them from the comfort of their living rooms to the exhilarating high frontier of modern science.

Nigel Calder was the son of Lord Peter Ritchie-Calder, a journalist who believed passionately in the potential of technology for improving society. Calder was born in London in 1931 and grew up there through the Second World War; the family were bombed out of their home during the Blitz. He was educated at Merchant Taylors’ School and, after National Service, the University of Cambridge. It was there, studying natural sciences, that he met and married his wife, Liz. They celebrated their diamond wedding anniversary earlier this year.

The place the Calders chose to bring up their family – and, in fact, live for their whole married life – was chosen, as are many things in life, entirely at random. While hitch-hiking, Calder and his wife just happened to be given a lift by the housing officer from Crawley New Town. So, Crawley it was.

After graduating in 1954, Calder took a job as a research physicist with Philips at its Mullard Laboratory in Surrey, not far from Crawley. Everything changed in 1956, however, when Percy Cudlipp, former editor of the London Evening Standard, and Tom Margerison started a weekly science news magazine, New Scientist. Calder, who had always been a communicator as well as a scientist, became Science Editor, commuting to a little office building in a quiet alley leading into Gray’s Inn in London.

“We had to invent a magazine,” wrote Calder in New Scientist’s 50th anniversary edition. “No one, not even the editor, could know exactly what it would be like until the first copies came off the presses.” Sales of the magazine were good but advertising sparse and, by the summer of 1957, the venture was looking precarious. But then, the magazine had an extraordinary piece of luck: the Russians launched Sputnik 1, giving birth to the Space Age, and suddenly everyone was interested in a popular science magazine. New Scientist never looked back.

In 1962 Cudlipp died, at the early age of 57. Calder took over his job, becoming New Scientist’s second editor. There he stayed for four more years. But in 1966, he wrote a science documentary for the BBC, Russia: Beneath the Sputniks. It was well received, and so he gave up a salaried job to pursue a freelance career in television – a brave move given that he was father to three girls and two boys.

Calder blossomed in TV. His forte was coming up with concepts to intrigue, inform and inspire, and turning them into two-hour blockbuster documentaries, accompanied by a best-selling book. The first, in 1969, was The Violent Universe. It was the time of Apollo 11’s landing on the Moon so Calder could not have picked a better time. In the book, subtitled “An Eyewitness Account of the New Astronomy”, Calder wrote: “We live in a relatively peaceful suburb of a quiet galaxy of stars, while all around us, far away in space, events of unimaginable violence occur. There are objects so disorderly that they seem to violate even the laws of physics.”

In 1972, The Restless Earth presented the idea of continental drift, which, despite being proposed by Alfred Wegener in the 1920s, was only just becoming mainstream. It illustrated Calder’s great talent for catching a scientific wave, spotting a new idea in science before it had fully emerged into daylight. “Plate tectonics”, as it became known, was still so controversial that, for a while, geology students had to rely upon The Restless Earth.

During the 1970s Calder unravelled and explained genetics in The Life Game, climate science in The Weather Machine and relativity in Einstein’s Universe. He summed up the immense power of Einstein’s mathematics in 11 words: “His equations incorporate the origin and fate of the entire universe.”

In the 1980s and ’90s Calder worked increasingly closely with the European science community, as a member of the Initiative Group for the Foundation Scientific Europe and general editor of its book, Scientific Europe. He returned to television, switching to Channel 4 for Spaceship Earth, another globe-girdling production about the impact of space technology on our understanding of the planet.

During the 1990s much of his work was for the European Space Agency. It was during this decade that Calder became embroiled in climate debate. In The Manic Sun: Weather Theories Confounded, he reported the controversial work of the Danish physicist Henrik Svensmark, who claims that climate responds principally to cloud cover, which he contends is governed by fluctuations in high-energy particles from space known as cosmic rays.

Calder was predisposed to tell such a story because he had seen how, in the case of Wegener and continental drift, one man, despite being right, had been frozen out by the scientific community. He wrote: “When Nazi scientists showed their solidarity against the Jewish doctrine of relativity, in a book called A Hundred Against Einstein, the hairy fellow growled that one would be enough. He meant that adverse evidence from Nature produced by a solitary researcher could destroy theories that no amount of ranting could touch.”

At the start of the 21st century, Oxford University Press commissioned Calder to write Magic Universe: The Oxford Guide to Modern Science. It was shortlisted for the Aventis Prize for Science Books. In his spare time, Calder was also a keen sailor. He won the Best Book of the Sea award for his 1986 book, The English Channel, about the hydrology, history and economics of that narrow stretch of water.

How will Nigel Calder be remembered? “As someone who explained the universe to the world,” said his son Simon, travel correspondent for The Independent. “And, with my mother, a kind, wise parent who brought up five children and empowered them to do interesting things with their lives.”

Nigel David McKail Ritchie Calder, science writer: born London 2 December 1931; married 1954 Elisabeth Palmer (two sons, three daughters); died Crawley, Sussex 25 June 2014.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments