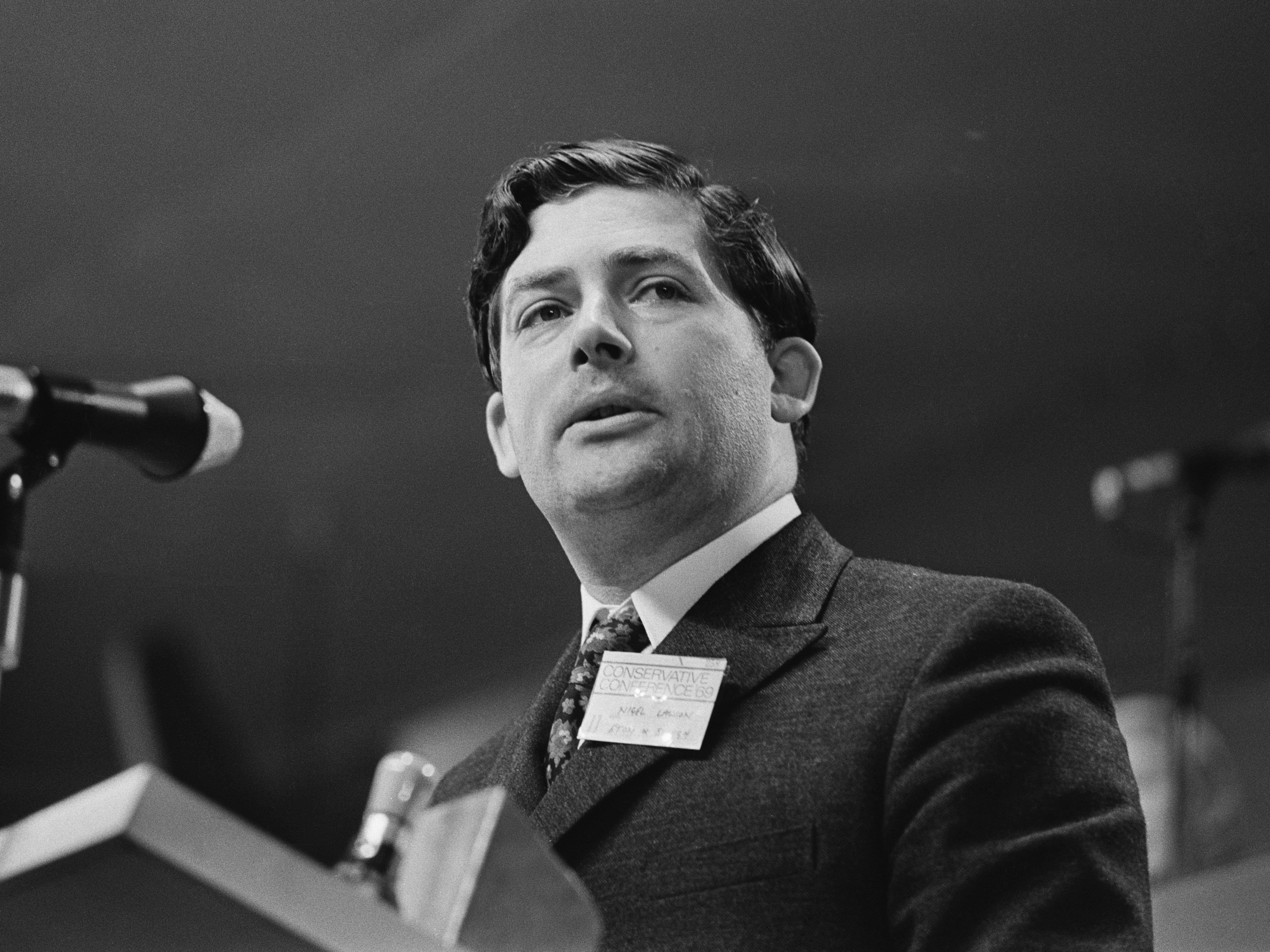

Nigel Lawson: Innovative chancellor who ushered in an economic shift

His various tax reforms made under Thatcher helped move economic policy from Keynesianism to monetarism

A man of powerful intellect, Nigel Lawson, who enjoyed one of the longest tenures of any post-1945 chancellor, provided the underpinnings and coherence for Thatcherism. The latter was a collection of values and instincts which the leader had gained in Grantham and Lawson is one of a handful of politicians who, without becoming prime minister, significantly shaped the British political agenda.

At the time of his tax-cutting Budget in 1988, Thatcher hailed him as a financial genius. He was delivering tax cuts, low inflation and falling unemployment and had pioneered privatisation. In many respects he was the architect of mid-term Thatcherism.

But when he resigned 18 months later, his relationship with Thatcher had collapsed and the verdict of the Daily Mail was that he had become a “bankrupt chancellor”. “The Lawson boom” was a painful legacy for his successors, and Labour politicians made mileage out of the “Tory years of boom and bust”.

Lawson was born in March 1932, the only son of a prosperous tea merchant, a Lithuanian who had fled Russia’s pogroms in the 1890s. His mother’s family were wealthy stockbrokers. He was bright enough to win a scholarship to Westminster and then gained a first in PPE at Christ Church, Oxford, specialising not in economics but philosophy. After graduating, he spent two years with the navy, becoming commander of his own ship.

The noted talent-spotter, Gordon Newton of the Financial Times, recruited Lawson to the paper. He then moved on to the Sunday Telegraph as City editor, inventing its City page, returned to the FT in 1965 and became editor of The Spectator in 1966 in succession to lain Macleod.

At university, Lawson had shown more interest in acting and playing poker than politics. He ignored the Oxford Union and the university’s Conservative Association, both magnets for would-be Tory politicians. But he was on the right and was recruited as a speechwriter for the new Conservative prime minister, Alec Douglas-Home, in 1963. He fought and unexpectedly lost the winnable Eton and Slough in the 1970 general election and had some difficulty finding a safe Conservative seat. Finally, he was chosen for and won the safe Blaby constituency in Leicestershire, in the 1974 election.

As a young man, Lawson had seemed to be assured of a golden future. He was an innovative journalist, his brain power was widely remarked, and aged 23 he had married the 19-year-old Vanessa Salmon. But the loss of The Spectator post in 1970 and election defeat that same year was followed by the failure of his marriage. His wife went off with Sir Alfred Ayer, the philosopher. He had also speculated and lost large sums of money in the 1974 stock market crash.

Before the “who governs?” election in February 1974, he had been taken on at the Conservative Research Department to help with political strategy. He was the first influential adviser to advocate an early general election because of the worsening economic situation. The good days were now over and the government should prepare the public for economic sacrifice. After much discussion, Heath called an election, but too late to catch the favourable tide in public opinion.

When Thatcher became leader of the Conservative Party in 1975, Lawson moved easily into her circle and, along with Norman Tebbit and George Gardiner, helped her to prepare for her Question Time jousts with prime minister, James Callaghan. In Thatcher’s first government, he was made financial secretary to the treasury and was more influential than most such holders of the post. He, with David Hancock, later treasury permanent secretary, and Bank of England officials, played a major part in the decision to abolish exchange controls.

In March 1980, he unveiled the medium-term financial strategy (MTFS), which announced gradually more restrictive monetary and borrowing targets over the next four years. But he was to find that the ending of exchange controls had the unintended consequence of undermining the practical basis of monetarism. His self-confidence and energy made him an imperious subordinate to chancellor Sir Geoffrey Howe.

In September 1981, Lawson was promoted to secretary of state for energy, with a seat in the cabinet. Coming from the Treasury, he was disappointed at the calibre of officials in his new department. He was an evangelist for privatisation and brought the British National Oil Corporation to the market. A young civil servant who caught his eye in preparing the programme was Richard Wilson, later a member of his Private Office at the Treasury and eventually cabinet secretary in 1998. Lawson also began to build up the coal stocks and move them to the power stations, “in case of a miners” strike.

Following the Conservative success in the 1983 general election, Howe moved to the Foreign Office and Lawson became chancellor. This was a remarkable rise after only nine years in the Commons. He was an innovative chancellor, more than able to hold his own with his officials, and was helped by Howe’s legacy of low inflation. The two men achieved the shift in economic policy from Keynesianism to monetarism.

These were happy years for Lawson. He lived in No 11 with his second wife and two young children, and for the first few years he had a friendly neighbour next door at No 10. He continued with the supply-side reforms and incentive measures to make the enterprise economy work. At the Treasury and at Energy, he threw his weight behind the privatisation programme and was an influential member of the key cabinet committee (ENA).

His major achievement, however, was in taxation. The key strategic decision was to pursue fiscal neutrality, an idea worked out in opposition with Howe and advisers. This involved scrapping many tax reliefs and special discriminatory features and using the extra revenue to reduce the overall rate of corporation tax. In 1984 he reformed corporation tax so that the tax bore more heavily on profits than employment. The 1988 Budget was breathtaking in cutting the top rate of income tax from 60 per cent (to which Howe had reduced it) to 40 per cent, and the standard rate to 25 per cent. He failed, however, to persuade Thatcher to abolish completely tax relief on mortgages and also had to allow tax relief for private health insurance premiums for the over-60s.

It is a tribute to his measures that this income and corporation tax structure was largely accepted by his successors, Conservative and Labour, and he did the groundwork for the long-term trends in taxes and public spending.

The growing authority of the Treasury in the 1980s contrasted with its eclipse in the late 1970s. His opposition to the Community Charge or poll tax was subsequently vindicated. He decided not to attend the key meeting at Chequers in March 1985, which gave the scheme momentum. He had believed that its defects were obvious. Some weeks later he wrote to Thatcher dismissing the scheme as “unworkable and politically catastrophic”.

Lawson was a distinctive politician. Formidably clever, resourceful in debate and persuasive on paper, he always appeared to argue from first principles. Because he did not suffer fools gladly, it was easy to understand how fellow MPs felt that some of his affability was forced. He was no orator. His conference speeches were flat (usually drafted at the last minute and he lacked the patience or humility to take advice) and his parliamentary contributions were sometimes delivered in a rushed, almost disdainful manner. But he was effective in the chamber.

His self-confidence often came across as dogmatism and arrogance. But his Treasury officials respected him and some found him delightful. Some economic commentators were more sceptical, even before he dismissed his critics as “teenage scribblers”.

By 1985, Chancellor Lawson had abandoned monetarism. Finding that M3, or broad money, and other monetary indicators were unreliable, he turned to the exchange rate to provide the anchor for anti-inflation policy and to stabilise sterling. Lawson understood that after the abolition of exchange controls, it was difficult to control the monetary aggregates in an economy. In the policy, change lay the seeds of his conflict with Thatcher. She took seriously her title as first lord of the Treasury and insisted on expressing her views on all tax and interest rate changes.

The immediate cause of the conflict was the question of Britain’s membership of the ERM under which a number of governments agreed to limit the fluctuations in their exchange rates against one other. By 1985, Lawson was convinced of the case for Britain joining the ERM. Lawson wanted to use the ERM as the anchor for monetary policy, as a growing number of countries were successfully doing. At meetings with Thatcher in January and then in September and November, the last two with various ministers and officials present, he attracted widespread support for British membership. Thatcher, with a small minority, vetoed the idea.

It is worth noting that, when the issue arose in the late 1980s Lawson opposed full economic and monetary union as a step too far in limiting national sovereignty. The ERM was a halfway house between floating and fixed exchange rates. A frustrated Lawson then decided to shadow the deutsche mark, without announcing it. Thatcher claimed to have heard of it only in late 1987 and was furious, privately describing his behaviour to staff as “traitorous”. She did not believe in fixed exchange rates and, reinforced by Waiters, claimed that one could not “buck” the market. In May 1988, interest rates were down to 7.5 per cent but by the time of the October party conference they had risen to 15 per cent and inflation was rising.

In June, Lawson and Howe threatened a joint resignation unless Thatcher made more positive moves about the ERM at the forthcoming Madrid summit of European leaders. Although she was furious about the joint threat, she accepted membership as a goal at Madrid, once certain conditions were met. In the government reshuffle the following month, she demoted Howe to Leader of the House of Commons and Lawson was exposed.

By now Lawson was totally fed up with the PM, and what he regarded as her arrogance and her “court”. The neighbours were no longer good friends but talked professionally on all economic matters except for monetary policy. His patience finally snapped. On 26 October 1988, he had the first of three tense meetings that day with Thatcher. He insisted that Walters must go or he would resign. She dismissed the suggestion and subsequently claimed to find it difficult to believe that Lawson could be serious.

Lawson was almost certainly correct to resign. Leaving aside the substance of their disagreement, it was politically and economically impossible to have such a fundamental division on economic policy at the top, and to have it publicly aired. It unsettled the markets and the Conservative Party, and encouraged the opposition. He regarded management of the exchange rate as the means of achieving financial discipline and she rejected the idea. His resignation came at a crucial stage in undermining Thatcher. Almost exactly a year later, Howe also resigned and set in motion the events which led to her fall.

Thatcher strongly suspected that Lawson, faced with mounting economic problems, was looking for an excuse to resign. It made no sense, however, for Lawson, conscious of his reputation, to leave at this point with inflation double the figure which he had inherited, interest rates at near-record levels and a large current account deficit.

In the party’s leadership contest in November 1990, he voted for Michael Heseltine over Thatcher. In the second ballot he pointedly did not vote for John Major, who had earlier been his chief secretary at the treasury, supporting Heseltine again. After his resignation, he made few interventions in the House of Commons and retired as MP at the 1992 general election, when he was elevated to the peerage as Lord Lawson of Blaby. He worked hard on his memoirs and in spite of their length (over 1,100 pages) and almost exclusive concentration on the 10 years of his ministerial career, The View from No 11: Memoirs of a Tory Radical (1992) had great impact and were very well reviewed.

Lawson’s first marriage to Vanessa Salmon produced four children, including the journalist Nigella, and the former Sunday Telegraph editor, Dominic. The two were in settled relationships with other partners long before the marriage was dissolved in 1980. That same year, Lawson married his secretary, Terese Maclair and had two children with her.

Nigel Lawson, former chancellor, born March 1932, died 3 April 2023

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies