Professor G. K. Hunter: Shakespeare scholar and founding Professor of English Literature at Warwick University

G.K. Hunter was a Renaissance man. But while he was a brilliant champion of marginalised Elizabethan playwrights like Lyly and Marston, his commitment, as scholar, editor and teacher was very much to the present, as his continuous engagement with Shakespeare demonstrated. He was among those pioneering academics who, in the wake of the 1963 Robbins Report, were tasked with tackling elitism, gender discrimination, and class-and-culture prejudice in higher education by widening participation, establishing, from the ground up, seven new universities in the UK. Hunter founded the Department of English and Comparative Literary Studies at Warwick University. His achievement was to imagine a new Humanities ethos for a changing world.

He was born in Glasgow in 1920. After graduating from Glasgow University, he joined the Navy, served on the Atlantic convoys, then, having learned Japanese, was posted to the Allied Pacific Headquarters in Sri Lanka. (Much later, Hunter would be known to introduce some debate or other in faculty meetings with, "as the only Orientalist present . . .") After the Second World War, he took a DPhil in Renaissance English Literature from Oxford, then held lectureships in Hull, Reading and Liverpool before being recruited to Warwick in 1964. His impact was immediate and sensational.

George Hunter saw culture as a continuum, an inheritance that authors have cherished or challenged and scholars have tried to comprehend for as long as writing has existed. Or even before: the European epic tradition, from Gilgamesh and Homer to Dante and Milton, was the foundation stone of the English syllabus he devised. Students were stretched by oral traditions and dizzying national myths while, simultaneously, they burrowed through the evolution of the English language via the Gawain poet, Langland and Chaucer. But Harold Pinter was on this syllabus, too – put there by Hunter before the playwright's name was at all known. For Hunter, past and present were in dialogue, and he was committed to discovering new voices. (One of his last Warwick lectures, after he had gone on to a distinguished career at Yale, introduced Jacobean revenge tragedy via the film Reservoir Dogs).

In establishing a department of "Comparative Literary Studies", Hunter was insisting that English could only properly be understood in a European context. He required all English students to become proficient in at least one foreign language and to take highly demanding courses outside their field. He himself worked fluently in five languages, two of them dead; didn't see the need of translating quotations (because everyone read Latin and Greek – didn't they?); and unhesitatingly gave readers passages of early modern Scots dialect, trusting to a literacy in them as capacious as his own.

To achieve his hugely ambitious vision for English at Warwick, Hunter head-hunted a brilliant team of rising specialists – including Claude Rawson, and Bernard Bergonzi – Americanists, linguists, poets, and such new talents as Gay Clifford (the youngest academic in Britain when she was appointed) and Germaine Greer (who juggled teaching, writing and appearances in a TV comedy show.

For students, these were heady times. The campus under construction on the green field site at the bottom of Gibbet Hill might be a sea of mud – more Wilfred Owens' Somme than William Blake's New Jerusalem – but that didn't matter. Everything there was to be invented: social structures, political structures, the very idea of what a university would be. Intellectual and generational turmoil were the order of the day, with student protest raging not just against what was happening in Vietnam, Mississippi and Northern Ireland but across universities too. He gave students a model of political engagement absent of factionalism.

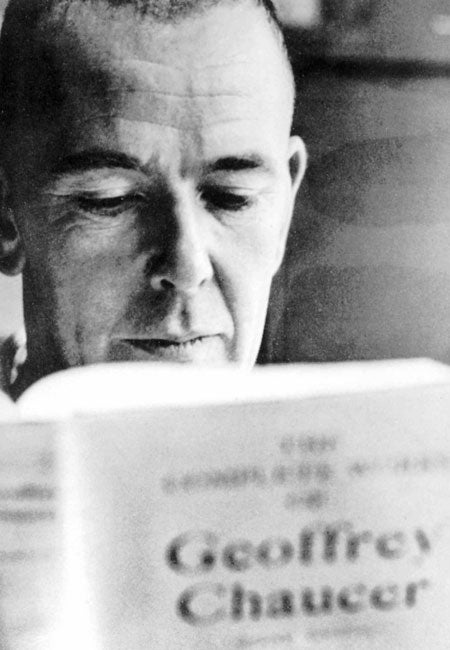

And he created, at the centre of those days' storms, a still space of almost monastic dedication to scholarship. He even looked monkish, shambling between buildings in a belted gabardine, a canvas knapsack over his shoulder, holding his sandwiches – an image at odds with his habits of mind. Absolute clarity was Hunter's trademark. Reading, writing, conversing, arguing – his research was exhaustive, his logic flawless. Everything mattered. Everything he produced was polished.

His remarkable critical and editorial work has remained indispensable because of the absolute standards he set himself and expected of others, whether writing a learned monograph like John Lyly: the Humanist as courtier (1962), contributing to the Oxford History of English Literature or editing Macbeth or King Lear for Penguin – and for the new mass readership the Butler Education Act had created and his new university was built to instruct and serve.

His brilliance was to begin with disarmingly "simple" questions, wondering, for example, what the "theatrical purpose" of Othello's blackness might have been. Astonishingly rich and detailed answers followed, sweeping magisterially across history, geography, myth; etymology, demographics, visual and print culture; finishing with Elizabethan playhouse practice and close readings of text. Essays like "Elizabethans and foreigners" (1964) and "Othello and colour prejudice" (1967), collected in Dramatic Identities and Cultural Tradition (1978) may show their age in their titles but as scholarship remain unsurpassed.

Undoubtedly, he made his greatest mark as a Shakespearean. He respected the pastness of the past, requiring students to encounter Shakespeare as an Elizabethan, a foreigner, on the playwright's cultural terms. He was the perfect go-between: his knowledge of the period was formidable. But he was also one of the first to understand Shakespeare not just as a writer of texts but a "wrighter" of performances, a man of the theatre whose words achieved meaning in the mouths of actors. Hunter forged important relationships with the Royal Shakespeare Company (which flourish at Warwick today), bringing in Peter Hall as an Associate Professor and laying the foundations for pioneering, internationally influential Theatre Studies and Film departments.

His Shakespeare showed how culture learns from the past and teaches the future. Only George Hunter in those days could insist on Shylock's and Othello's inextricability from medieval church art, Venetian journals, Dachau, and Notting Hill. His Shakespeare was in dialogue with all writing: Homer (refracted and savaged in Troilus and Cressida); Petrarch (made to dance by Romeo and Juliet); Tolstoy and Melville (grappling with the nightmares of history, faith and obsession that galvanise King Lear).

And – he made this explicit – his Shakespeare was the crowning experience of the Warwick degree, the place where English students would apply their critical skills and test their imaginations to the limit. Attending his lectures was like going to the theatre. Students didn't take notes. They absorbed the performance – and wrote it up afterwards. His lectures could be inspirational, even hilarious, but dangerous too, as he suddenly leaned across the podium to pick out some hapless individual to explain a dense passage of rhetoric or supply a date.

Combative and witty, suffering no fools gladly but deeply concerned, a perfectionist with a hawk's sharp eye and boots thick with the dust of experience (some of it, students suspected, picked up in a past life on the road between Stratford and London, in deep conversation with Shakespeare), Hunter taught students that the values and humanity which great literature conserves are worth fighting for. He engaged in that battle every day of his life.

Carol Rutter and Tony Howard

George Kirkpatrick Hunter, English scholar: born Glasgow 7 October 1920; Lecturer in English, Hull University 1948-56; Lecturer in English, Reading University 1956-58; Lecturer in English, Liverpool University 1958-64; Professor of English Literature, and Founding Head of Department, Warwick University 1964-75; Professor of English, Yale University 1976-87, Chair of Renaissance Studies 1985-91, Emily Sanford Professor of English 1987-2008; FBA 1988; married 1950 Shelagh Edmunds (one son, two daughters); died Topsham, Maine 10 April 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments