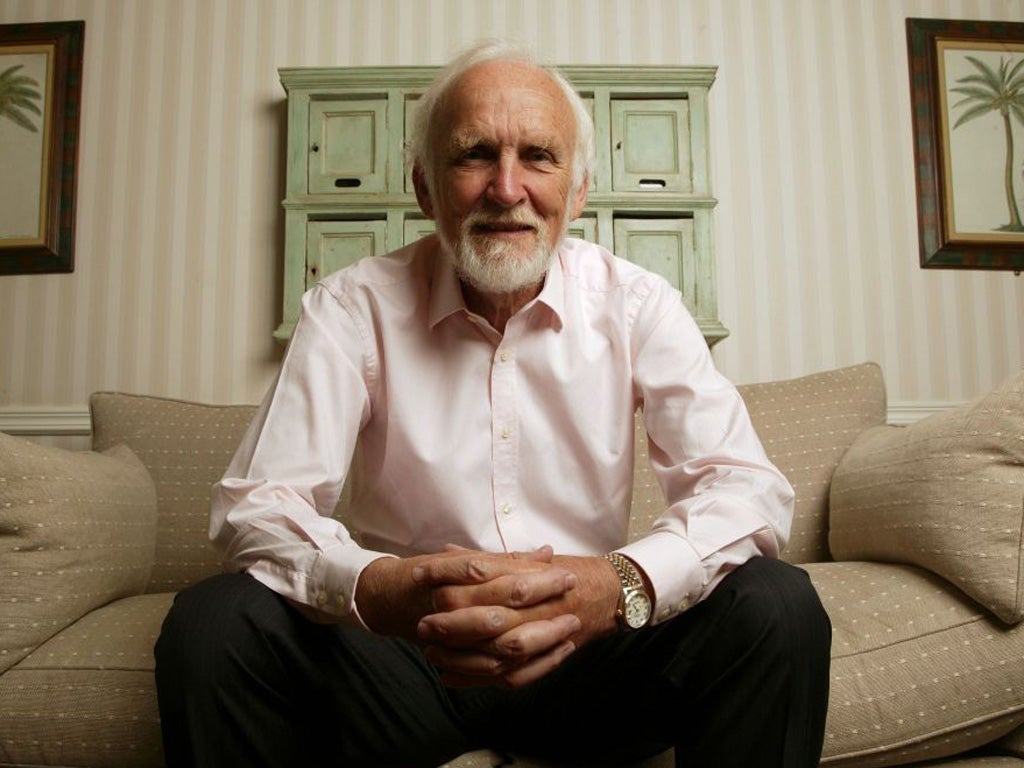

Reginald Hill:Crime writer best known for hisdetectives Dalziel and Pascoe

In a 1993 interview with The Independent, the best-selling crime writer Reginald Hill said: "It is easy to mystify. The good mystery writer's real skill lies in clarification." At the time he was in his 23rd year as a published author but was less generally known than he deserved to be for his series of cunningly constructed mysteries featuring Dalziel and Pascoe. That changed when, in 1996, 11 years of successful TV productions began. The 20-odd Dalziel and Pascoe novels were less than half of Hill's output but he long recognised them as his "bankers". The two characters he created – a modern pairing of Falstaff and Hal – are probably the most interesting characters in modern crime fiction.

Reginald Charles Hill was born in Hartlepool, Co Durham, in 1936. His father was a professional footballer for the town's club. Hill wrote of the town, with typical humour, that its main claim to fame "is that its inhabitants are alleged to have put a shipwrecked monkey on trial during the Napoleonic wars and when it answered all their questions in what they presumed was French, they hanged it as a spy."

At the outbreak of the war his father moved the family when Hill was three, to Cumberland. Hill had two brothers, David and Desmond. His mother was a keen reader, especially of crime fiction, and Hill always said he discovered books collecting them for his mother from the library. Hill was educated from 1947 at what was then the Carlisle Grammar School. Between 1955 and 1957 he did his National Service in Germany.

Demobbed, he studied English at St Catherine's College, Oxford, then taught in Essex: "Armed with a degree in English, I stepped trembling into the real world and found it occupied a space somewhere between the idiocies of the army and the absurdities of Oxford."

At Oxford he had played rugby with a middle-class man whose name was pronounced "De-ell". "It took me a little time to realise this chap, who I was putting my arms around in the scrum, was the same as the person listed on the team sheet as 'Dalziel'. Later when I was looking for a gross Northern copper, I thought how amusing it would be to call him after my rather smooth middle-class friend." He married Patricia Ruell in 1960. They'd known each other for 10 years and remained married until his death. He shifted from schools to college, lecturing at the Doncaster College of Education, Yorkshire, where he remained through the 1960s and '70s.

He recalled: "I had been making up stories as long as I could remember, and writing them down as long as I could write. I had known I would one day become a writer in the full sense ever since I reached an age when looking into the future took me beyond an interest in what I was likely to be getting for tea."

The dozen or so novels he wrote in the 1960s were rejected but he had success in 1970 with his first Dalziel and Pascoe, A Clubbable Woman: "It was as if a block had been removed. I had two published in 1971 and three in 1972. I didn't wait for the heavy thud as the manuscript came back through the door – I started the next one. I can't think where I got the energy for it all."

In the '70s he produced 18 novels, short stories and a play, An Affair of Honour, for the BBC, and a comedy sketch for Dave Allen. He also wrote as Patrick Ruell, Dick Morland and Charles Underhill as well as Reginald Hill.

In 1980 he retired from lecturing to write full time. The hallmark of his novels is that they are intricately plotted, beginning with disparate strands which he weaves together by the final chapter. In the best of them, such as Bones and Silence, An April Shroud or Beulah Heights, even when you think he has given you all the answers, there is always one more thing he tells you that you didn't realise you didn't know.

He explained: "Plot is the basis of narrative interest, the force that drives the reader along paths which seem totally mysterious ahead, but which appear clear as day behind."

Dalziel (large, loud and often loutish) and Pascoe (a social science graduate with a radical wife) represented two sides of his own personality. "When I started I was more inclined towards Pascoe, because I wanted to write about someone like me who might have joined the police after university. Dalziel has shouldered his way centre stage, however." Dalziel often comes across as a stage-Yorkshiremen, blunt, beefy and boorish. "But he can also be sensitive, charming and courteous," Hill argued. "And really Dalziel and Pascoe are one person. I'd like to be Pascoe but Dalziel is always there waiting to burst out."

In 1990 he won the Crime Writers' Association's Gold Dagger award for Bones and Silence and in 1995 the Cartier Diamond Dagger for his outstanding contribution to crime fiction.

Yorkshire Television held the rights to Dalziel and Pascoe for many years. Hill had always seen Brian Blessed as the perfect Dalziel, though in the pilot, A Pinch of Snuff, the detectives were played by the comedians Hale and Pace. It was a disaster and ordinarily that would have been it. But in 1996 the books were picked up by the BBC.

When the company decided to cut Pascoe's wife Ellie from the series, he wrote his next Dalziel and Pascoe, Arms and the Woman, from her viewpoint. Off-stage at the Edinburgh Book Festival that year he said: "Let's see them film that." His most recent Dalziel and Pascoe was published in 2009. Hill said: "I write on a need-to-know basis and my need to know is much greater than that of the readers. I write hundreds of pages too much and then cut it down."

He was the most literate of writers and enjoyed playing around with literature in his novels. But he was no literary snob. Several years ago at a crime festival he was on a panel with the literary writer John Banville (aka crime writer Benjamin Black). Banville was saying how each day he didn't know whether to carve out a few well-honed sentences for a literary novel or write a couple of thousand words for a Benjamin Black. Hill agreed. "I know – every morning I say to my wife, 'Shall I work on my Booker novel today or my best-selling crime novel? But you know, it's funny – every day I say I think I'll do the best-seller." Thank goodness he did.

Reginald Hill, teacher and writer: born Hartlepool 3 April 1936; married Patricia Ruell; died 12 January 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments