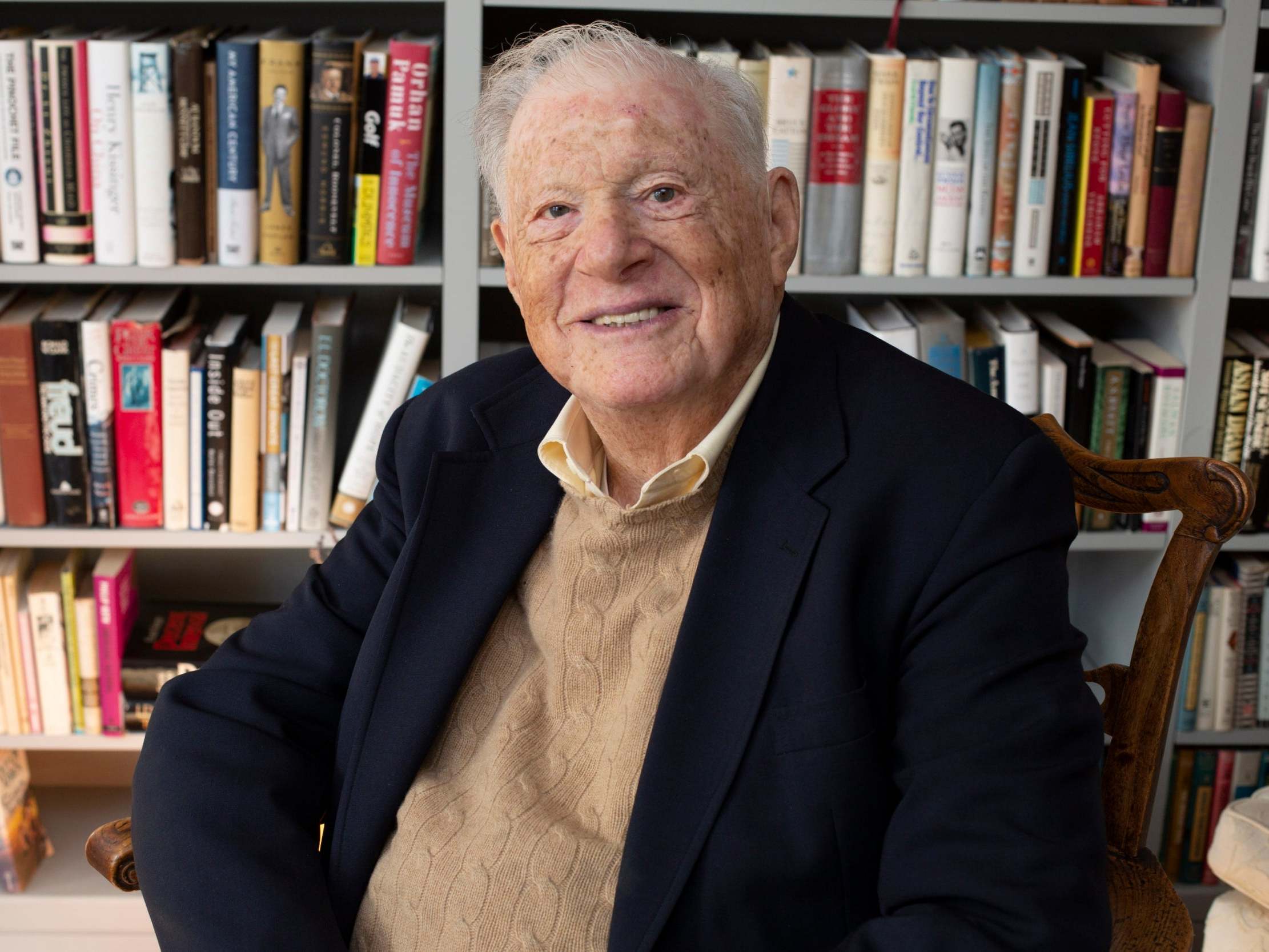

Robert Bernstein: Publishing colossus who led Random House and founded Human Rights Watch

The champion of writers such as Toni Morrison, Norman Mailer and Dr Seuss led a parallel life as a campaigner

Robert Bernstein, who has died aged 96, bestrode the publishing industry for more than two decades as the chief executive of Random House and who helped to pry open closed societies around the world as the founding chair of Human Rights Watch.

At 6ft 3in tall, with freckled features and a low-key leadership style, Bernstein began his career as a junior office boy at Simon & Schuster and rose to become the president, chief executive and chair of America’s most renowned publishing house.

Under his direction, Random House expanded into the world’s largest general-interest publisher, increasing revenue from $40m in 1966, when he was named president, to more than $800m in 1989, when he was forced into retirement.

The company added paperback divisions, enlarged its textbook and nonfiction offerings, and negotiated a lucrative distribution deal with smaller publishers, including Warner Books and Reader’s Digest Press.

As the industry was transformed by corporate consolidation and a growing thirst for bestselling titles, Bernstein retained Random House’s reputation for literary excellence – as well as what The New York Times once described as “the rambling quirkiness of a large bookstore run by somebody with a passion for books”.

A courtly Harvard graduate, Bernstein hired Toni Morrison as an editor, then arranged to release her novels through one of his many imprints, Knopf. He also published writers including Cormac McCarthy, James A Michener, EL Doctorow, William Styron, Norman Mailer, Robert Ludlum and Dr Seuss, who became a family friend.

For decades, he spent what few free hours he had promoting human rights, a passion that deepened in the 1970s when he visited Moscow with a delegation of American publishers.

His meetings with dissidents such as Andrei Sakharov, the nuclear physicist and Nobel Peace Prize laureate, led him to create the Fund for Free Expression, a group of writers, editors and other literary figures concerned with rights abuses around the world.

In the aftermath of the 1975 Helsinki Accords, he also formed Helsinki Watch to monitor the protection of basic freedoms in the Soviet bloc. It was followed by similar organisations centred on the Americas, Africa, Asia and the Middle East, which merged in 1988 to form Human Rights Watch.

Bernstein sometimes held board meetings for the organisation at Random House’s headquarters in Manhattan and participated in its research activities first-hand. In 1985 he flew to Nicaragua and drove “to within 20 miles of the Honduran border”, according to a New York Times report, “to investigate charges that acts of terrorism were being waged by the contras against unarmed civilians”.

Combining his interests, Bernstein published works by dissidents around the world, including Sakharov and his wife, Yelena Bonner; Natan Sharansky, a former Soviet political prisoner; Jacobo Timerman, who was tortured by Argentina’s military government in the 1970s; and Vaclav Havel, the Czech statesman and playwright.

Like his predecessor, Random House co-founder Bennett Cerf, who successfully pressed for the full publication of James Joyce’s “dirty” masterpiece Ulysses, Bernstein also took on government censorship – notably with The CIA and the Cult of Intelligence (1974), a critical account of the agency by Victor Marchetti and John D Marks.

After the CIA demanded the removal of 339 passages on national security grounds, Bernstein and Knopf filed a lawsuit backed by the American Civil Liberties Union. The agency relented on many of the changes, and the book became a bestseller after it was released with 168 blank sections, marked with the word “Deleted”.

Bernstein’s tenure at Random House was shaken by the arrival of SI Newhouse Jr, who bought the company from RCA in 1980 for $70m. Although the two got along well at first – Newhouse had reportedly insisted Bernstein remain to run the company – they ultimately battled over Bernstein’s decentralized approach to management.

Bernstein had described Random House as “a mountain range instead of a mountain” and gave wide latitude to his executives and editors, a group of all-stars that included Jason Epstein, André Schiffrin and Robert Gottlieb. But after Bernstein and Random House acquired imprints including Crown Publishing, Fodor’s travel guides and Schocken, costs soared and profits dried up.

“The company got so big, it needed a more hands-on style of management,” Newhouse said, explaining his decision to replace Bernstein with a more business-minded executive, Alberto Vitale.

Bernstein shifted his focus to Human Rights Watch, which was active in 70 countries by the time he stepped down as chairman in 1998. That same year, President Bill Clinton honoured him as one of the first recipients of the Eleanor Roosevelt Award for Human Rights, calling Bernstein “a pathbreaker for freedom of expression and the protection of rights at home and abroad”.

The older of two children, Robert Louis Bernstein was born in Manhattan in 1923. His father worked in the textile business, and his mother was a homemaker.

Bernstein received a bachelor’s degree from Harvard in 1944, served in India with the army air forces, and was working towards a career in television or radio when a family friend arranged a meeting with Albert Leventhal, an executive at Simon & Schuster.

The friend, Bernstein once said, “thought that I wanted to be a writer. He was wrong.” He kept the appointment anyway, thinking it would be rude to decline, and was offered a job as “assistant to the office boy” – with weekly pay that was $5 better than his radio gig.

Bernstein rose through the ranks but was fired in 1956 amid a wave of cutbacks and battles with executive Leon Shimkin. He was working out of the Plaza Hotel, helping children’s author Kay Thompson develop a merchandise line based on her Eloise character, when Cerf recruited him to join Random House.

Bernstein was named president within a decade, chief executive in 1967 and added the title of chairman in 1975. After leaving the company, he joined John Wiley & Sons as publisher-at-large and founded organisations including Human Rights in China and Advancing Human Rights. Human rights fellowships and institutes were named in his honour at Yale and New York University.

In 2009, he took the unusual step of criticising the organisation he had founded, writing in an op-ed column for The New York Times that Human Rights Watch had issued reports “on the Israeli-Arab conflict that are helping those who wish to turn Israel into a pariah state”.

The group, he argued, was better served focusing on closed authoritarian states such as Iran than condemning violations of international law in Israel. (Two chairs of the organisation disagreed with his reasoning, writing in a letter to The New York Times that “it is essential to hold Israel to the same international human rights standards as other countries”.)

Survivors include his wife of 68 years, the former Helen Walter; three sons, Peter Bernstein, Tom Bernstein and William Bernstein; a sister; 10 grandchildren; and four great-grandchildren.

In interviews, Bernstein often credited his success at Random House to the close ties he fostered with his writers – including Kay Thompson, who celebrated his first day at the publishing house by placing six pigeons in his desk area as a prankish welcome gift “from Eloise”.

“An author has to feel that they know an editor,” Bernstein said in 1991. “A book company is a service company for authors – it edits them, promotes them and, in a way, it has to love them.”

Robert Bernstein, publisher and human rights activist, born 5 January 1923, died 27 May 2019

© Washington Post

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies