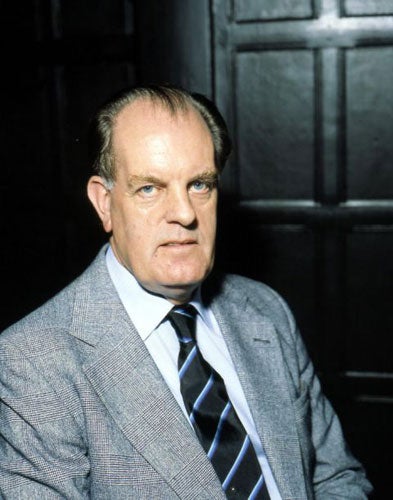

Sir Denis Rooke: Engineer and chairman of British Gas who battled Nigel Lawson over the privatisation of the industry

The Queen bestows the Order of Merit only on a few who have achieved exceptional distinction. Denis Rooke, OM, Fellow of the Royal Society, pioneer of liquid petroleum gas, and chairman of British Gas plc and under its previous nomenclatures from 1976 to 1989, richly deserved the honour.

He was also held in the highest regard by discerning politicians in a position to know – by James Callaghan, Prime Minister during Rooke's first years as British Gas chairman, Tony Benn, then Secretary of State for Energy, John Smith, with whom as minister of state Rooke had day-to-day working relations; and equally on the Conservative side, the Energy Secretary Peter Walker, and William Waldegrave, Science minister in the early 1980s, who said that Rooke "was of that great period when engineering and scientific knowledge was still allied to the highest managerial abilities".

However, Rooke's relations with Nigel Lawson, Secretary of State for Energy between 1981 and 1983, were, as he told me (using one of his favourite words), "cryogenic". This was because Lawson was trying to break up Rooke's beloved gas industry and privatise it as several separate companies.

The high opinion of key ministers was shared by those of us who were regular attendees at the Parliamentary and Scientific Committee to which Rooke regularly came. His contributions to our discussions after the guest speakers had spoken, and at the formal discussion sessions at the dinners which followed in Dining Room A of the House of Commons, were a powerful combination of modesty and blunt forthrightness. He was the arch enemy of any sign of cant among politicians, scratching for easy options.

As Secretary of the Parliamentary and Scientific Committee, often sitting next to him, I asked the direct question: "Denis, why did you decline the offer which I know from John Smith was made to you by James Callaghan, and subsequently on at least one occasion by the Conservative government, to go to the House of Lords?" His reply encapsulated his character: "I have many friends in the Lords, whom I respect greatly, and frankly their Select Committees on energy and science matters do a better job than yours in the House of Commons. But throughout my life, I have taken the view that either I do a job properly or not at all. To 'do the Lords properly' I believe that one has to be a regular attendee, week in and week out. My other interests simply do not permit anything approaching acceptable attendance." He was the clearest of thinkers, not least about his own position.

Rooke's great technical achievement and lasting legacy was to build Britain's gas distribution network and unite the hitherto somewhat diverse gas industry, which had its roots in Morrisonian municipalisation making domestic gas a cheap and convenient fuel source for millions of people. As deputy chairman, Rooke oversaw the restructuring that turned the 12 area boards of 1948 into regions of the newly created British Gas Corporation in 1973. And indeed the British Gas Corporation did provide excellent service. Overwhelmingly, his employees were enthusiastically loyal to Rooke and regarded him as the defender of their gas company against any silliness from political meddling.

After a great deal of argument and much hectoring from Margaret Thatcher, Rooke struck a deal with Peter Walker, Lawson's successor as Secretary of State for Energy, whom he greatly respected. Instead of breaking up the industry into separate enterprises, the gas transmission, distribution and retailing business was turned, by Act of Parliament in 1986, from a publicly owned single monopoly into a single private sector monopoly, British Gas plc. Without Rooke this beneficial outcome would certainly not have happened. Seldom has one man had such a decisive influence on major public decision-making by the force of his character. His physical presence – large, craggy, with a lantern jaw – no doubt helped.

Denis Rooke was born in 1924, at New Cross, south-east London, the son of a printer who was also from time to time a commercial traveller for print machinery; Rooke always said that he understood the importance of manual dexterity for an engineer from the example of his father. After attending Westminster City School and Addey and Stanhope School, in New Cross, he went to University College London where he graduated in 1944 in mechanical and chemical engineering.

His first-class degree smoothed the way to a commission and rapid promotion to the rank of major in the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers. He was sent to India at a time when there was a real threat from the Japanese army towards the end of the Second World War. Later, he reflected that this was a seminal experience and brought home to him a determination that the problems of world poverty would only be solved by technological skill and advances.

On demobilisation he joined the staff of the South Eastern Gas Board as an assistant mechanical engineer specialising in coal-tar by-products. He became a deputy manager of works in 1954 and was seconded to the North Thames Gas Board in 1957.

He told me that it was a stroke of luck that had brought him, a working-class, self-made boy, to the attention of the chiefs of the gas industry. There was a very dangerous cargo in the London docks which, had it not been dealt with correctly, could have created an explosion, wreaking havoc. Rooke was the young manager who led the team on to the ship and made the right decisions to quell the chances of catastrophe. Contemporaries in the industry long since dead told me that Rooke had been extremely brave as well as technically superb.

The industry chiefs realised what they owed him and smoothed the way for him to take charge of the work in Britain and America on liquefied natural gas and of a technical team which sailed in the tanker Methane Pioneer on the first voyage bringing liquefied natural gas across the Atlantic to Britain in 1959. He became chief development engineer of the Gas Council in 1960 and member for production and supplies 1966-71. After four years as deputy chairman he was to spend the next 13 years as chairman of the Gas Council, which became the British Gas Corporation in 1973 and from 1986, British Gas plc.

Tony Benn told me that Harold Wilson had wanted to make Rooke chairman of the British National Oil Corporation in 1974. "As Secretary of State I put this offer to Rooke but he was not keen on it, and so Sir Frank Kearton was appointed instead." Later, when I talked about this offer to Rooke, he told me that his instinct was that there would be too much ministerial meddling and interference for his taste and that he wouldn't touch it with the proverbial barge pole.

Rooke had many tangential interests. From 1978 to 1983 he was chairman of the Council for National Academic Awards; from 1972 to 1977 he was a member of the Government's advisory council on research and development and agreed to serve on the board of the British National Oil Corporation, 1976-82. He was an important member of Neddy (the National Economic Development Council) from 1976 to 1980 and president of the Fellowship of Engineering 1986-91.

A very particular interest was as a trustee of the National Museums of Science and Industry, of which he became chairman in 1995. A fellow trustee, Sir Michael Quinlan, former Permanent Secretary at the Ministry of Defence, and a connoisseur of quality chairmanship, told me that Rooke was a "hugely effective" chairman of trustees. Quinlan added that not only did he concern himself with the world-famous Science Museum in Kensington but that he took a special interest in developing the Railway Museum in York and the National Museum of Photography in Bradford. Rooke himself showed us superb pictures of wild flowers that he had taken as an amateur photographer.

From 1989 to 2003 Rooke was Chancellor of Loughborough University. Sir David Wallace FRS, Vice-Chancellor of Loughborough 1994 to 2005 (and now Master of Churchill College, Cambridge) told me that Rooke was "absolutely engaged with the university. In 12 years he only missed graduation on two occasions, when he was called to receive the Order of Merit and when he went to Cambridge University to collect an honorary degree. He shook the hand of every single graduate, all 3,000 of them. He participated in Court beyond anything one might reasonably expect of a chancellor of a university."

Tam Dalyell

Denis Eric Rooke, engineer and industrialist: born London 2 April 1924; assistant mechanical engineer, South Eastern Gas Board 1949-54, deputy manager of works 1954-59 (seconded to North Thames Gas Board 1957-59), development engineer 1959-60; development engineer, Gas Council (British Gas Corporation from 1973, British Gas plc from 1986) 1960-66, member for production and supplies 1966-71, deputy chairman 1972-76, chairman 1976-89; CBE 1970; Kt 1977; FRS 1978; Chancellor, Loughborough University 1989-2003; OM 1997; married 1949 Elizabeth Evans (one daughter); died London 2 September 2008.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies