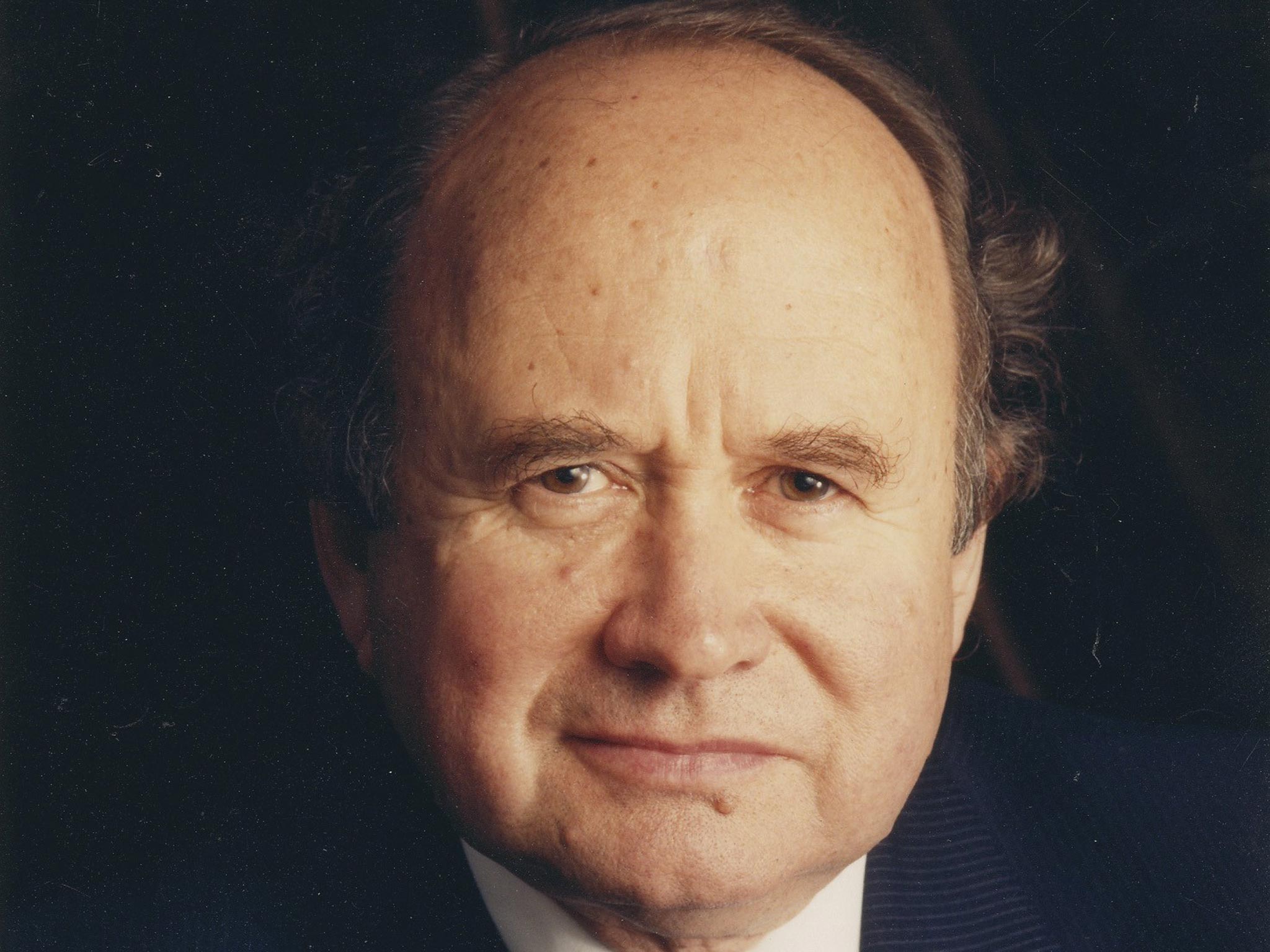

Sir Graham Hills

Scientist whose distinguished career in chemistry was followed by huge success as Vice-Chancellor at Strathclyde

The huge success of the University of Strathclyde can be in no small measure to its first two vice-chancellors, Sir Sam Curran (1964-80) and Sir Graham Hills (1980-91).

I can testify to that success. As a Central Scotland MP I talked to many constituents who had graduated from Strathclyde, often in their late twenties, after working in industry. Invariably their experience had been first class.

I asked Curran about his successor. “Hills is aware of the importance of practical skills and industrial partnerships,” he said. Apart from being a first-class chemist he has the experience of management gained from being Dean of Science and Deputy Vice-Chancellor of the excellent University of Southampton.” Curran’s hopes were more than fulfilled.

Born in 1937 in Leigh-on-Sea, a fishing village in the Thames estuary, the son of a Wesleyan Methodist builder, Hills won a scholarship to Westcliff High School, but had to leave with a minimum of qualifications at 15. The family had been bombed out of their home and had to rely on various boarding houses.

He took work as a laboratory assistant – but, as he said, “I struck lucky. May and Baker were a leading chemical company. Two of their employees, over 70 and called back from retirement to replace men called up into the Army, took a kindly interest in me.” Hills gained a practical experience of industry, invaluable to him at Southampton and Strathclyde.

They encouraged their lab assistant to enrol part-time at Birkbeck College. Hills attended evening classes and devoted his weekends to serious study, achieving a BSc in chemistry in 1946. It is understandable that he became an outspoken champion of widening access to higher education before it became conventional wisdom. “There was a lively chemistry department which was continuing to educate gifted strays, especially refugees from Hitler’s Germany,” he recalled. “Standards were high, conversation and debates outstanding. This was the Birkbeck of Joad, Bernal, Blackett, Cookson, Ingram, Bradley and Ives. It was from Ives that I acquired a mastery of thermodynamics which was to last a lifetime.”

In 1950 Hills received his doctorate and was invited by Imperial College to become a lecturer in physical chemistry. He told me that he was once more lucky in his departmental seniors. Professor Frank Hartley took an interest in Hills’ research in electrochemistry, and was in a position to make sure crucial funding was available. And there was the patronage of the formidable (and irascible) Sir Ernest Chain, Nobel Prize-winner.

In 1962 Imperial recommended Hills to Neil Adams, Dean of Science at Southampton University, for the Chair of Physical Chemistry, which he was to occupy for 18 years, developing the department into one of the leading faculties in Europe. Later, his contribution to electro-chemistry and the electrical sciences was recognised by his election as President of the International Society of Electro-Chemistry (1983-85). He was Visiting Professor at Western Ontario in 1968, Case Western Reserve University in 1969, and Buenos Aires in 1977 (he later let it be known to students that he was opposed to the Falklands War). He would invite any international students to spend Christmas in his home.

The 1980s were a difficult time for university finances but Strathclyde weathered the storm better than most, thanks to Hills’ persistence in establishing links outside the academic world, enabling it to tap into new sources of funding. I attended several of his dinner parties and marvelled at the way he set about getting serious money from the guests. He was so cheerful and open about it all – so disarming! New students’ residences were built on campus; the Barony Church was bought and restored for use as a ceremonial hall.

Hills had an up-and-down relationship with his colleagues on the Committee of Scottish Vice-Chancellors. The fact that he was a pungent, witty and much sought-after after-dinner speaker may not have helped. And, he told all of us who cared to listen that “My hobby is rocking the boat.” His stream of contentious letters to the Scotsman and Glasgow Herald were, as one Scots Principal sighed to me, “A cross that has to be borne.” Sir David Smith, Vice-Chancellor at Edinburgh from 1987-93, told me, “Graham was good at his job, very quick-witted, and he made us fellow vice-chancellors just a little nervous.”

After he retired Hills directed his thrusting energies to the creation of the University of the Highlands and Islands. He served a five-year term as the BBC’s National Governor in Scotland and cultivated international academic contacts, particularly with the University of Lodz in Poland. He had shown a special interest in the Polish community in Scotland, and in his many half-Polish/half-Scottish students. Hills, and his ever-supportive second wife Mary McNaughton, received honorary doctorates from Strathclyde on the same day in 1991. Hills was described as “a remarkable man, a man of vision, intellect and compassion whose considerable talents were used for the benefit of the University on the local and international stage.” Very true.

Graham John Hills, chemist: born Leigh-on-Sea 9 April 1926; Kt 1988; married 1950 Brenda Stubbington (died 1974; one son, three daughters), secondly Mary McNaughton (died 2013); died Edinburgh 9 February 2014.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies