Trade Union Bill: how the bakers and other unions are finding new ways to compel employers to act

Changes in the workplace, the law and public attitudes have robbed trade unions of membership and influence. But in today’s labour market, the low-paid need them more than ever. Simon Usborne asks how the comrades are rising to the challenge

There were a lot of horrible jobs in the mid-19th century but for sheer drudgery and reduced life expectancy, you could do little worse than make bread. In London alone thousands of "journeyman" bakers worked 20-hour days, inhaling flour and sleeping in shifts on wooden boards. "With the exception of the unhappy persons employed in bleach works, there is no body of men so painfully placed," the National Magazine told its readers in 1860.

Demand was high, competition rife, and wages as poor as the health of bakers. Yet, as an earlier article read: "It is extremely difficult to see how, according to existing tastes, and in present circumstances, the condition of operative bakers is to be improved."

But millions of workers in newly industrialised countries were organising and in Manchester something stirred. In 1847, a group of bakers formed a union. Public awareness of their plight grew, and by 1863 the government, under pressure, passed the Bakehouse Act. Bad news for employers, but, for their employees, earning a crust became less of a death sentence.

More than 175 years and a few name changes later, the Bakers Union still exists. Its president is Ian Hodson, a former biscuit baker from Blackpool now navigating one of the biggest periods of change in his union's long history, one that is reflected across the labour movement at a crucial moment of renewal and threat.

"Our industry is shrinking," Hodson says from the tiny Tottenham, London HQ of the Bakers, Food & Allied Workers Union. "People aren't going into the massive industrial sectors. Now we're getting members in from KFC, McDonald's, Burger King, Pizza Hut. At our conference recently we had workers from Nando's. And they're all under the age of 24."

As the divisive Trade Union Bill continues through parliament, diversification is, increasingly, one way unions are adapting to a changing workforce, and responding to a slow decline in membership and influence. In 2014, more than 6.4 million people, or 25 per cent of all workers, were members of one of more than 40 unions. Significant, but less than half the movement's peak of 13.2 million in 1979, the year of the bitter Winter of Discontent and Margaret Thatcher's rise to power.

Much of the focus of the Bill has been the proposed thresholds to limit strike action. Yet strikes, even taking in falling membership, have become rare.

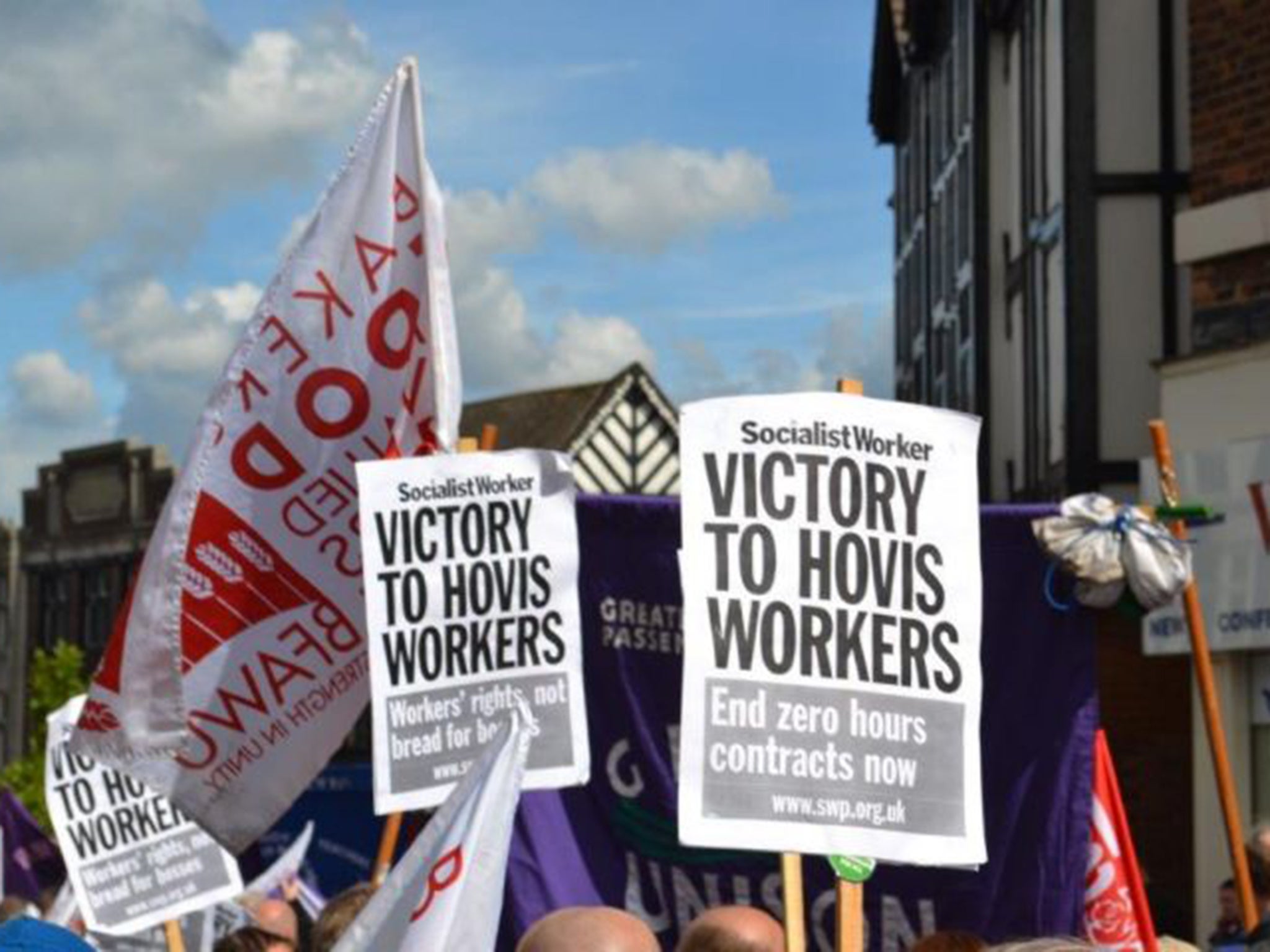

In 1979, Britain lost almost 30 million worker days to walk-outs. Last year, just 788,000 days were lost, even at a time of cuts and economic hardship. "We've had three disputes in the past five years that were really necessary," Hodson says. "And only two of them ended up with workers going on strike." (Last month, the Bakers Union resolved its dispute with a Hovis plant in Wigan over its use of zero-hours contracts.)

Under the new proposals, which would severely limit the way strikes are balloted and conducted, at least half of workers who are members would have to vote, one way or another, for a majority result to lead to action. Additionally, in core public services, at least 40 per cent of members would have to vote "yes" for any walkout to be legal. The Government says the changes are necessary to balance the right to strike with the right to work and to, say, catch a Tube train at 3am or see a GP on a Sunday. But critics have described them as undemocratic (they note that, for example, only 22 per cent of eligible voters elected a majority Conservative government) and a telling statement of intent.

The Government also wants to allow agency workers to replace striking staff, and proposes that picket supervisors would need to tell police the names of strikers. David Davis, the Conservative MP, has asked if this measure might belong in "Franco's" Britain.

Taken together, the changes amount to "the biggest attack on trade unions and workers' rights for more than 30 years", Frances O'Grady, the General Secretary of the Trades Union Congress, tells me. And they come during a period of fraught debate about labour disputes, in the NHS and on London Underground, as well as Labour's leftward shift under Jeremy Corbyn. But a lot of that discussion conceals the already changing face of industrial relations, particularly in the private sector.

Which brings us back to the bakers, as well as the warehouse grabbers, the waiters, the chambermaids and the cinema ushers. While public-sector union membership declines (it's down to 3.8 million), private-sector membership has been quietly rising since 2010, and now stands at 2.7 million. The sector itself is growing too, but unions say the rise reflects a new approach.

For the Bakers Union, it increasingly means looking beyond bakeries to workplaces where old tactics don't cut it any more. In a branch of KFC, a union has little hope of signing up enough members to even push for recognition from the employer. High staff turnover, agency work, language and awareness barriers, employer resistance and employee fear all make those conversations tough. "The more that business globalises and fragments, the harder it is to sit across a table from the employer who holds the purse strings," O'Grady says. "Yet unions are the last line of defence against unfair and unreasonable treatment in a country where most people see the balance of power in the workplace having gone massively in favour of the employer."

It’s very difficult to explain the level of fear there is on site at Sports Direct. It’s palpable

So unions are stepping back from the table – and the picket line – to use other ways to organise workers and compel employers to act. The Bakers Union has led a campaign in the fast food industry for a £10 per hour living wage. Members have staged protests outside branches where customers might not be aware that the 17-year-old inside is earning the hourly minimum for his age of £3.79. Protests are noisy on the pavement and on social media, triggering local media coverage and further momentum.

Unite, Britain's biggest union with more than 1.4 million members, is also working to improve conditions in the sector with the lowest union representation ("accommodation and food services" has only 4 per cent membership. Education tops the league with 50 per cent). In less than 10 years, a campaign led by Dave Turnbull has picked up more than 3,000 workers in the sector, including in hotels. "But they are scattered and disparate," the Unite veteran says.

The union ramped up its campaign for fair tipping this year. More than 85 per cent of waiting staff are paid below the minimum wage, depending on tips to make any sort of living. Yet many profitable chains take a cut of those tips. By following the same route, via protests, and social and old media, Unite made enough noise, without employees needing to negotiate with managers, to prompt Pizza Express to scrap its tip-skimming policy last month, and for the Government to order an inquiry into tipping practises across the industry.

"We've realised that for the type of industries we're looking at you've got to think outside the box and use a bit of leverage on the company's reputation to win for workers," Turnbull says. "That also gives workers the confidence of a platform to organise."

Among many barriers to that kind of organisation, everyone identifies the same big one. "It's very difficult to explain the level of fear there is on site," says Luke Primarolo, who runs Unite's campaign to protect workers at Sports Direct. "It's palpable, you can almost cup it." The sportswear giant employs around 4,000 people at its HQ and warehouse in Derbyshire, the majority via recruitment agencies on minimum wage and zero-hours contracts. So-called "fulfilment centres" have become the mills of the 21st century, part of the modern retail landscape. While unions grew in response to industrialisation, they are having to think smart in the face of globalisation.

Unite began looking seriously at Sports Direct when reports emerged last year that a worker had given birth in a toilet on New Year's Day. Evidence then emerged of a "strike" system in which six misdemeanours would result in dismissal. "Strikes you get for things like 'excessive chatting', long toilet breaks or periods of reported sickness," Primarolo says. But a vanishing proportion of staff – fewer than 100 – have so far dared to join the union.

Unite is working in the community around the warehouse to increase awareness, and offers English lessons for the largely East European workforce. Members who are not employees have staged dozens of demonstrations outside Sports Direct stores, where thousands more staff are also denied a living wage. Last month, a protest outside the company's AGM gained widespread news coverage, alongside a large social media campaign. The company, which is majority-owned by the billionaire Mike Ashley, says it "complies fully with all legal requirements which relate to casual workers" and strongly denies accusations of mistreatment, but it remains under pressure.

Unions are finding that for many demographics, being visible is only part of the battle. Industrial relations mean different things in an increasingly diverse workforce. "People from some parts of Latin America may perceive being in a union as being a huge threat to their personal safety because of the way unions are received in some countries there," says Turnbull, whose work towards a living wage in hotels could not be more international. "Then you've got people from France or Scandinavia who can't understand why we don't have the automatic right to representation."

Youth engagement is another challenge. Twenty-two per cent of union members are under-35 (yet they make up almost 40 per cent of the workforce) compared to almost 33 per cent 20 years ago. Just four per cent are aged under 24. Are stereotypes of militant men of a certain age with red faces and red politics to blame for putting them off? Hodson has pushed the Bakers Union to recent prominence partly as a result of its noisy support for Jeremy Corbyn. He has also called for civil disobedience in the fight against the Trade Union Bill, and in July he compared David Cameron to Hitler in a tweeted attack on the plans to regulate strikes. "Bread and Gutter" was the headline in The Sun. "At the time it felt right, and I never meant to offend anyone," Hodson says. "Look, politicians are not seeing the consequences of their policies so yes we're passionate because we're seeing it first-hand."

"Of course we've got people who can still get a hall going and that's great," adds O'Grady, who points out that 55 per cent of union members are women. "But somehow the old film clips from the '70s are still wheeled out. We need to keep spirits high but we're also a modern, diverse movement and we've got a lot of potential, I think, to reach a whole new generation of workers."

In many workplaces, young people are not even aware of the stereotype. "There's a whole generation of people who don't really know much about trade unions at all," says Melanie Simms, a professor of work and employment at the University of Leicester. But engaging them is not about challenging an image problem, she adds. "They don't even remember Blair, let alone Thatcher. It's important for unions not to bring assumptions about what they know when talking to them. They don't remember the things that you do."

When they are reached, unions find young people are no less inclined to organise. Ask junior doctors, who are threatening to strike in a dispute over a proposed new contract. "All sorts of surveys show that young people are the same in their individual or collectivist values, they just don't join things, whether that's a church, a sports club or a trade union," Simms says.

Those instincts were evident at a cinema in South London which last year became an unlikely symbol of a new kind of dispute. Customers at the Ritzy Cinema in Brixton pay more for a glass of Merlot in a plastic glass than staff earn in an hour. Rents and the cost of living have soared. Staff were fortunate in that union recognition had been won several years earlier, but membership had dwindled to below a third.

There has never been a more important time to build not just union membership but a movement for fairness at work

"There were a few people who you'd say, 'hey, guys, do you know we're unionised… do you know what a union is?' and they'd say, 'No'," recalls Ritzy worker Nia Hughes, who led a campaign for a living wage at the cinema that started in 2013. "But then you'd ask them, 'how much are you worth? Are you happy with what you're being paid?' And that made them think. Often young people have such low expectations. They think it's normal to work 40 hours a week in a gallery for nothing just so they can put it on their CV. We wanted them to be aware that they don't have to choose to be part of that culture."

Within months, Hughes, 33, had helped boost membership at the Ritzy of Bectu, the media and entertainment union, above 80 per cent. Meanwhile, the campaign began to raise awareness outside the cinema, which is part of the formerly independent Picturehouse chain now owned by Cineworld. Local newspapers and blogs picked up the story and residents began to tweet. When management refused to budge, workers began a series of walkouts last year. Coverage intensified and went national. Film heavyweights Ken Loach, Terry Jones and Eric Cantona lent their support, and cinemagoers boycotted other Picturehouses. Eventually, the company agreed to a 26 per cent pay rise over three years.

The Ritzy dispute included a picket line but Hughes says social media was the bigger force. "It was essential," she says. "The picket line has its place but it's not the only way to implement change now. Unions have a reputation for being old school but I think we showed that you can go about protesting in a contemporary, modern way. We also showed how important awareness is."

"A lot of them don't know the alternative," Hodson adds. "They don't know that there used to be some guarantees." The 52-year-old started out as a baker when unions were at their peak. "We worked with leaflets but young people do it through music or film or social media. They have ideas of their own, and it's really refreshing."

The coverage and tone of the reforms – and the proposals themselves – suggest the status of the unions is uncertain, longer term. While only 25 per cent of workers are union members, 43 per cent work in places with a union. That's a big gap, and efforts to organise and appeal outside traditional industrial relations can only achieve so much. O'Grady is bound to be positive but she says more can be done. "I think in many ways we may be facing the biggest threat but we're also facing the biggest opportunity, because there has never been a more important time to build not just union membership but a movement for fairness at work."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments