9 things the Sony hack has taught us about Hollywood

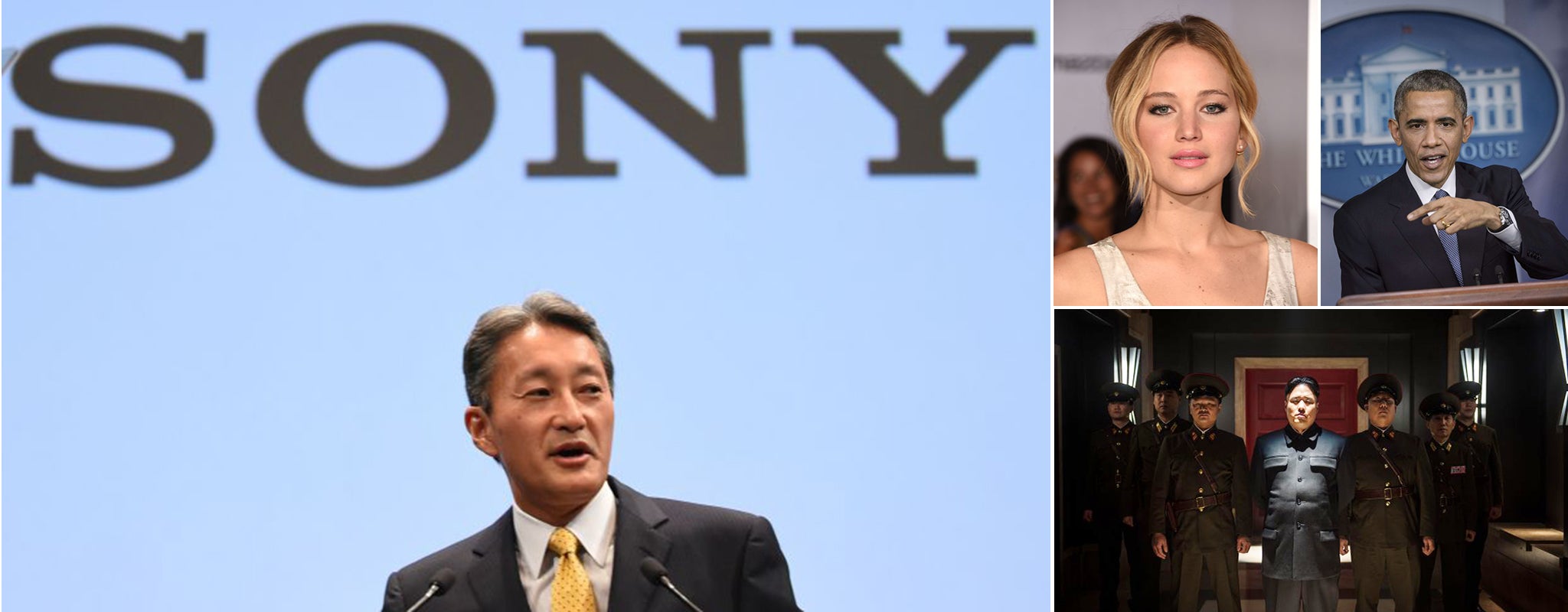

The Sony cyber-attack gives a rare insight into the film business. Tim Walker reports from LA

Call it good timing or a chilling coincidence, but one of the most high-profile movie releases of January 2015 will be director Michael Mann’s thriller Blackhat, in which a brilliant hacker helps the United States authorities to pursue a cyber-criminal who hacks a Chinese nuclear reactor and a Chicago stock exchange with devastating results. The premise alone is enough to strike fear into the hearts of Hollywood executives, following the recent cyber-attack on Sony Pictures Entertainment.

The US today reiterated its belief that North Korea was behind the hack, despite a denial by the country’s Foreign Ministry, which offered to hold a joint inquiry into the attack with American investigators. “As the United States is spreading groundless allegations and slandering us, we propose a joint investigation with it into this incident,” the Pyongyang regime said in a statement, adding that there would be “grave consequences” if the US refused the proposal.

Last month’s cyber-attack, the largest ever on a company on US soil, crippled Sony’s computer systems, reducing some workers to using pen and paper. It also exposed the company to vast leaks of sensitive data, including employees’ details; financial records; and private emails between executives and other Hollywood players. In the process, the data dump provided a rare porthole into the mechanics of the film industry. This is what we have learnt.

Hollywood is more terrified of North Korea than you are

On Wednesday, Sony cancelled the Christmas release of the film that apparently prompted the attack. Hackers had made threats towards any cinema that showed The Interview, a comedy about two US television journalists sent by the CIA to assassinate the North Korean leader, Kim Jong-un.

A day after Sony’s capitulation, Paramount studios vetoed screenings of its 2004 comedy Team America: World Police, which several cinemas planned to show in place of The Interview. In Team America, Kim Jong-il is impaled on a spike and revealed to be an alien cockroach in disguise. In The Interview, his son and successor is killed in a rocket explosion.

Another North Korea-set film was scrapped this week by production company New Regency. Steve Carell was set to star in Pyongyang, a darkly comic thriller based on a graphic novel, which was slated to go into production next March.

President Obama said on Friday that Sony had “made a mistake” in capitulating to the hackers. “We cannot have a society in which some dictator some place can start imposing censorship here in the United States,” he said. “If somebody is able to intimidate folks out of releasing a satirical movie, imagine what they start doing when they see a documentary they don’t like, or news reports they don’t like. Even worse, imagine if producers and distributors and others start engaging in self-censorship because they don’t want to offend the sensibilities of somebody whose sensibilities probably need to be offended.”

The movies are running out of viable villains

Sony Pictures chief Michael Lynton responded to Mr Obama’s remarks by insisting the studio had not “caved”, and that it still hoped to release the film, perhaps via video on demand. “We have not caved, we have not given in, we have persevered and we have not backed down,” he said.

Yet in fact, Hollywood has been engaged in forms of self-censorship for years. Anxious not to offend the censors who control China’s booming movie market, Paramount last year altered its zombie epic World War Z, removing a potentially disparaging reference to China. In 2012, MGM spent $1m (£640,000) to digitally alter its film Red Dawn, transforming its Chinese villains into North Koreans. North Korea was then considered a commercially safe screen baddie. No longer.

Hollywood is increasingly limited in its choice of international antagonists. Earlier this year, some Russian politicians, incensed by the prevalence of Russian villains in Hollywood movies, pushed for new powers to ban foreign film releases that “demonise” Russia.

Sony’s parent company stays out of its creative decisions – with one notable exception

Even before North Korea started issuing threats, Sony bosses were concerned about the consequences of The Interview. For 25 years, the corporation’s Japanese CEO Kazuo Hirai has kept his nose out of its Hollywood production arm, Sony Pictures Entertainment. That tradition was broken this year when, worried about a possible response from Pyongyang, Mr Hirai insisted the film-makers soften a scene depicting the slow-motion death of Mr Kim, reducing the gory detail of a close-up in which the North Korean leader’s head explodes.

The demand led to a lengthy back-and-forth between studio chief Amy Pascal and Seth Rogen, the film’s star and co-director, as they tried to reach a compromise on how graphic the sequence would be. It also emerged in leaked emails that the studio sought the blessing of the US government, and that at least two administration officials screened and approved The Interview.

The studio chief may be female, but the industry still suffers from institutional sexism

A leaked spreadsheet appearing to list the salaries of 6,000 Sony employees showed that 17 of the studio’s US staff earn $1m or more per year. Only one of them is a woman: Ms Pascal, the Sony Pictures co-chair who green-lit The Interview. The studio’s Columbia Pictures division has two co-presidents of production, but Michael De Luca makes almost $1m more per year than his female counterpart, Hannah Minghella.

The pay gap also applies to acting talent. Emails from 2013 suggested the stars of Oscar-nominated American Hustle each had deals entitling them to “points” – a percentage of the revenue from the film. But while Christian Bale, Bradley Cooper and Jeremy Renner all had 9 per cent deals, Amy Adams and Jennifer Lawrence were getting only 7 per cent.

Bankable stars aren’t always beloved by their paymasters

They may be able to draw big audiences, but Hollywood idols don’t always elicit the unconditional affection of their colleagues. During an email discussion about Angelina Jolie’s long-gestating biopic of Cleopatra, producer Scott Rudin described the star as “a minimally talented spoiled brat”. In a separate exchange about Leonardo DiCaprio pulling out of a deal to play Apple founder Steve Jobs, Ms Pascal said his behaviour was “despicable”.

Actors really do use ridiculous aliases

If 2014 is anything to go by, then Hollywood stars have more cause than ever to be concerned about their privacy. Before the Sony hack came the August leaks of private, intimate images of female celebrities including Jennifer Lawrence and supermodel Kate Upton.

Little wonder, then, that actors use false names when their contact details are distributed to colleagues during a film’s production process. The Sony hack revealed, for instance, that Jessica Alba goes by the alias “Cash Money”, while Tom Hanks calls himself either “Harry Lauder”, the name of a Scottish vaudeville performer from the early 20th century, or “Johnny Madrid”, after a character on a 1960s TV Western.

Even top Hollywood execs make off-colour jokes in private

In one unfortunate email exchange leaked by the hackers, Ms Pascal and Mr Rudin joked about the cinematic tastes of President Obama, suggesting he would enjoy black-themed movies such as Django Unchained and 12 Years A Slave. Both apologised for the racially insensitive wisecracks, and Ms Pascal met on Thursday with the Rev Al Sharpton to discuss establishing a “working group” to tackle the lack of diversity in the film industry. Yet the pair were defended by director John Singleton in an article for The Hollywood Reporter. The black film-maker, who has worked with both Mr Rudin and Ms Pascal, wrote: “I don’t think either of these figures is racist or insensitive to any group.”

Studios have the same arguments about art and money as the rest of us

In one document, a Sony employee lamented the “blah-ness” of some of the studio’s product, singling out “mundane, formulaic Adam Sandler films” .Yet Sony is also a studio willing to take commercial risks, on films such as Moneyball, The Social Network, Zero Dark Thirty – and, let’s face it, The Interview.

Every studio wants its own Pixar “story trust”

The success of Pixar is thought to be largely a product of its “story trust” of directors and other filmmakers, who consult extensively on every film the animation studio makes. After Pixar impresario John Lasseter took over Disney Animation, he established a similar group there, and was rewarded with a string of hits including Frozen.

Keen to establish a story trust of its own, Sony this year tried to recruit Phil Lord and Chris Miller, writer-directors of The Lego Movie, to lead its animation division. But they declined the offer, and in emails cited the fact that Sony recently moved its visual effects outfit, Imageworks, to Vancouver for financial reasons, leading to an exodus of talent. “It’s too hard to do great work [at Sony],” Mr Lord wrote.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments