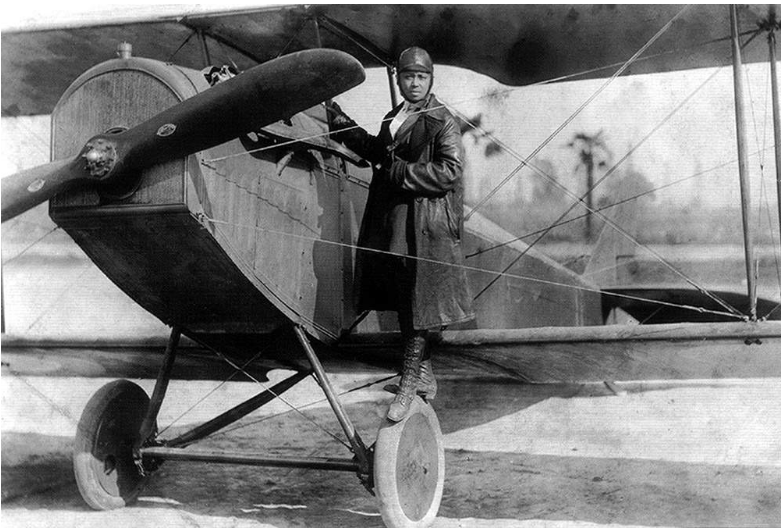

Bessie Coleman: First African American woman to get international pilot licence

Texan travelled to Europe to learn to fly when nobody in the United States would teach her

Pioneering American aviator Bessie Coleman is being honoured with a Google Doodle today, on what would have been her 125th birthday.

In 1921 Coleman became the first African American woman to be awarded an international pilot licence, and in 1922 the first to stage a public flight in the United States.

When flying schools at home denied Ms Coleman, who was also of Native American descent, entry, she taught herself French and earned her licence in Europe in just seven months instead, before returning to work as a stunt pilot.

Here is what you should know about her:

1. Coleman was born in Atlanta, Texas in 1892. She was the 10th of 13 children born to George and Susan Coleman, both farm labourers. Her mother was African-American and her father was part African-American and part Cherokee.

Coleman's family moved to Waxahachie, another city in Texas, when she was a small child. She walked four miles everyday to a tiny school, in which black and white students were segregated.

For several months each year she also helped her mother to harvest cotton. Her father left to move back to Native American territory in Oklahoma when she was seven, in search of better opportunities for the family.

In 1915, aged 23, she moved to Chicago to live with an older brother. She trained as a manicurist and allegedly excelled, becoming the best and fastest nail technician in the city according to one biographer.

Not long after her move to Chicago, she began listening to and reading stories about World War I pilots, which reportedly sparked her initial interest in aviation.

2. Because she was black and female, Coleman could not find any school or individual in the US willing to teach her how to fly.

She lived through several race riots in Chicago, including one of the largest in 1919, in which 38 people were killed, 537 injured and over 1,000 made homeless in four days of fighting after a black man was murdered by a group of white people.

In this period, Coleman befriended several African-American community leaders in the city, including Robert Abbott, who published the nation's largest African American newspaper, the Chicago Defender.

Mr Abbott suggested that Coleman go to France. He said the French were not only less racist and less sexist than Americans, but also world leaders in aviation.

The Defender and an African-American businessman, Jesse Binga, offered to fund Coleman's studies, keen to see a black woman become a pilot.

Coleman learned French, withdrew money she had saved from working two job — as a manicurist and manager of a 'chili parlor' Texan restaurant — and in November 1920 she travelled to Europe.

3. It took Coleman just seven months to learn how to fly at a school in France, where she was the only non-white student in her class.

She was taught in an eight metre biplane (an aeroplane with two wings stacked one above each other) that was known to frequently fail, sometimes in the air.

During her training, Coleman saw a fellow student die in a plane crash, which she described as a "terrible shock" to her nerves. Yet she persisted with the training and in June 1921 the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale awarded her an international pilot licence. She was the first African American woman and the first Native American woman to be awarded this licence.

She returned immediately to the United States, where she had become a minor celebrity, particularly in the African American press. She decided to take advantage of her newfound fame and launch a one-woman airshow, entertaining the public as a stunt pilot. However she needed more training to be able to do tricks, and she still could not find anyone willing to teach her in the US, so she returned to Europe for another year, this time visiting Germany and the Netherlands as well as France.

In 1922, she returned with new skills and more confidence, and began to travel around the US performing aerial acrobatic stunts, wing-walking, parachuting, and diving under the stage name Queen Bess.

Throughout her career, she would only perform at shows if the crowd was desegregated and allowed to enter through the same gates.

Her shows were immensely popular, and she also gave lectures about flying, often to predominantly black audiences who knew little about aviation.

At the height of her fame, she was asked to star in a film, but she walked off set on the first day because she said the film perpetuated racist stereotypes of African Americans.

According to biographer Doris Rich: "She had gladly accepted the role hoping it would help advance her career and provide her with money to establish her own flying school. But when she learned the first scene required her to wear tattered clothes, with a walking stick and a pack on her back, she refused to proceed."

Ms Rich added: "Clearly, her walking off the movie set was a statement of principle.

"Opportunist though she was about her career, she was not an opportunist about race. She had no intention of perpetuating the derogatory image most whites had of most blacks."

4. Coleman died in an accident on April 30, 1926, during a rehearsal in Jacksonville, Florida.

She was only 34. Her mechanic and publicity agent, William Wills, was also killed.

Coleman had recently purchased the plane they were flying in, and it is believed to have been badly maintained by the previous owner.

Mr Wills was flying the plane, and Coleman was preparing for a parachute jump when about 10 minutes into the flight, the plane engine failed. The aircraft went into a dive and then spun around. Coleman was thrown from the plane at 2,000 feet and died on impact with the ground.

Wills could not regain control of the plane and crashed into the ground.

Five thousand mourners attended a memorial service for Coleman in Orlando and an estimated 15,000 people paid their respects in Chicago.

5. When she died, Coleman was in the process of saving up to open her own flight school exclusively for black pilots.

“I decided blacks should not have to experience the difficulties I had faced, so I decided to open a flying school and teach other black women to fly,” she told a reporter.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments