Why world leaders are losing hearts and minds

Across the developed world, approval ratings for political leaders are plummeting. What's behind this dramatic loss of confidence – and can the power players bounce back?

Cometh the hour, cometh the man. But not as far as Western politics are concerned, apparently. All through Europe and America, as Japan, Western democracies are suffering a collapse of leadership and a catastrophic decline in popular confidence in them. It's not as though the need for leadership is not there. On most accounts, Europe and the US are now facing the greatest crises in their economies cohesion since the end of the Second World War.

Yet everywhere the ratings of democratic leaders have gone into virtual freefall. Mrs Angela Merkel, Germany's Chancellor, who only a year ago was being hailed as the most sensible and reliable leader of the Western world with full voter support, has now seen her ratings fall precipitously. Only 40 per cent of German voters now say they are satisfied with her performance, her lowest scores since she took power nearly six years ago. And her centre-right coalition has fared even worse, with only 12 per cent of voters saying they are satisfied with it.

It's even worse in France, where the ever-hyperactive President Sarkozy, despite a slight rise because the pregnancy of his wife and his leadership of the intervention into Libya, has approval ratings of only just over 20 per cent, compared with ratings of more than 50 per cent recorded by his predecessors, François Mitterand and Jacques Chirac at the same point in their terms, when they were also less than a year away from re-election. Unsurprisingly Silvio Berlusconi, the Italian Prime Minister, has seen his support fall from over 50 per cent only a couple of months ago to around 40 per cent on the latest figures. The wonder may be that he kept his rating so high for so long, considering the trials that now beset him. The Greek Prime Minister, George Papandreou, has meanwhile seen his ratings slide from over a third to around a quarter in two months, while David Cameron's are heading in the same direction with the Murdoch scandal. His latest approval ratings have fallen from 37 per cent to 33 cent over the last month. Of all European leaders only the Irish Prime Minister, Enda Kenny, is enjoying strong support, at 65 per cent, the highest for any Irish leader in nearly a decade – but then he has only been in office for four months.

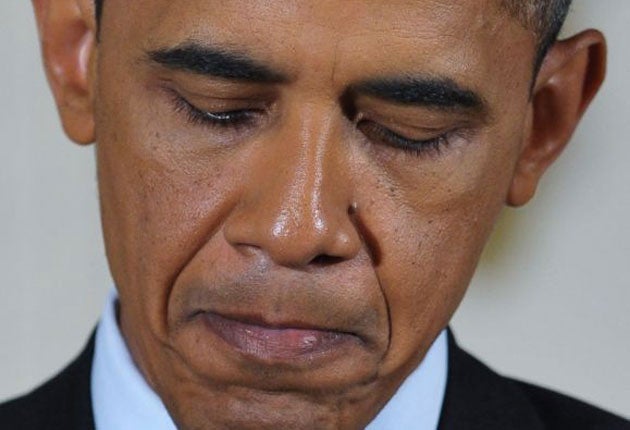

Go outside Europe and the Japanese Prime Minister, Naoto Kan, has managed to achieve the lowest approval scores of any current democratic leader with only 19 per cent of voters backing him. Most troubling of all is President Obama's inability to get his ratings from historically low levels, despite the killing of bin Laden. On the latest Rasmussen daily polling, only 25 per cent said they strongly approved of his performance as president compared with 42 per cent who strongly disapproved – a rating of minus 17, one of the lowest results since President Nixon was hit by the Watergate scandal.

You can't blame this all on a public growing tired with faces that have been there too long. Only Berlusconi has been in position for more than a decade. By post-War standards, Presidents Obama and Sarkozy are relatively fresh faces, still within their first terms, while David Cameron, Naoto Kan and George Papandreou have been in office for only a year or less. Nor can you put it all down to the normal process of disenchantment with leaders who seemed to promise so much when they were voted into office and then failed to deliver as reality overtook expectations.

That is part of it, no doubt, but it does not explain why the loss of confidence in Western leadership is quite so widespread and so dramatic. Nor can it be explained, as so often in the past, by a general shift between right and left. Chancellor Merkel, Nicolas Sarkozy and David Cameron are all of the right, but President Obama, Naoto Kan and George Papandreou are all left of centre – and all elected in a general rejection of their right-wing predecessors.

Economics is clearly the proximate cause. When the financial meltdown first occurred in 2008/9, it caught nearly every government unawares and unprepared. But at least it was perceived as a common threat which, partly thanks to Gordon Brown's leadership, produced a common front. Now that the immediate crisis has passed – or is perceived to have passed – the politics of recession and austerity has become a great deal more muddled and uncertain. On the one hand, most electorates seem to accept the need for belt-tightening. The days of "anything goes" are clearly over. On the other hand, when it comes to the precise nature of the cuts and the sharing of pain, voter support is a lot less certain. Governments – caught between the resentments of the public and the demands for budget reductions by the markets – have retreated into an ever more parochial indecision.

Chancellor Merkel is the most obvious case. Despite ruling over the most successful economy in the West, she has shifted stance, under the threat of widespread national defaults, to a nervous ambivalence between German nationalism and European interest. The demands for total Greek abnegation, along with calls for curbs on immigration and non-commitment on foreign ventures, have vied with a rhetoric of wider eurozone responsibility. Few could blame her for her increasing introversion in the light of her ratings and the drubbing her party has received in recent elections. But leadership it is not.

President Obama seems to be heading in the same direction. After all his talk of the need to keep the economy going through public expenditure, he too has been driven to a dispiriting attempt to meet the demands of opposition and polls in talking of ever deeper cuts to his budget. The peculiar nature of Congressional politics may have forced him in this direction but after all the hopes that the US at least would prove a beacon of Keynesian reflation, his retreat is disillusioning, as is his reluctance to project American leadership in the Middle East and Libya. Even President Sarkozy, while desperately trying to assert French international leadership in Libya and West Africa, has been forced by the polls to address domestic concerns with ever more virulent, and indeed racist, calls to bear down on immigrants.

It is a terrible comment on British politics that Gordon Brown, who really does have something to offer on economic and international affairs, should use only his second speech in the Commons since leaving office to speak on the Murdoch scandal. Of course, given hard times, electorates inevitably turn inwards to their own problems and democratic politicians feel the need to follow them. But leadership in a democracy requires that premiers rise above the imperatives of the polls to give a broader vision of the future in which voters can feel hope and confidence. Instead we have voted in a generation of leaders who seek refuge from the bigger challenges in the discussion of the specific and the parochial.

You can hardly argue that modern electorates don't seek leadership. The expectations loaded on President Obama were precisely because US voters, and many outside, wanted someone who represented a different and more sympathetic vision of the world than that of his predecessor, George Bush. So too with Naoto Kan, who was voted in as the first non-Liberal party premier in three generations. And, if David Cameron aroused much less widespread hope here, he did at least offer a fresh face. It may be that today's voters load politicians with impossibly contradictory demands. On the one hand most citizens – and this applies far wider than Britain – express contempt for politics in general and politicians in particular. Voter turnout has steadily dropped in most countries since the war and shows no signs of stopping its decline. On the other the hand the voters look to politicians to solve instantly problems of recession, budget, policing, health and climate change as if government had the power to wave wands and change everything. People want leadership but they don't actually want to join parties, stand for local elections or participate in the way a healthy democracy requires if it is to thrive.

Which is the chicken and the egg in this – whether lack of political participation is the consequence of failed politics or the cause of it – is a moot point. But either way the result has been a crop of politicians who have seen the job not in terms of belief or service but as a profession in its own right. It is not that government no longer attracts the brightest and the best. If you look across the cabinets of the Western world today, they are extremely well educated and intelligent. But in the search for electoral success they have become practitioners of the polls, ever seeking the nebulous middle ground to ensure their power.

This must be the first time in British history that the leaders of all three parties – David Cameron, Nick Clegg and Ed Miliband – have done nothing other in their lives than seek a career in politics. The same is now becoming true of the US administration and the governments of most European countries. It is also, it should be added, the first moment when virtually no leader of any country has had any experience of war.

Maybe the "vision thing" is not necessary when things are ticking along very nicely, peace is the order of the day and the economies have been growing apace, as most Western countries have in the past decade and more. Then Mrs Merkel's qualities of common sense and caution seemed sufficient and, indeed, much to be envied.

We're no longer in that period, however. The times are more than "interesting"; they have become really challenging and threatening. Look at almost every issue – from the threatened collapse of the euro to the faltering recovery in most economies, from the future of nuclear after Fukushima to the consequences of the Arab Spring – and you are seeing problems that demand both a decisive response and international co-ordination.

Look at the performance of the G8, the EU, and Nato and all you see are premiers simply incapable of rising to the occasion. The public may have unrealistic expectations of politicians but, on this, they are right. The current generation of Western leaders are simply not up to it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments