Are faith-specific war memorials the best way to remember the fallen?

Santanu Das on seeing past conflicts through the prism of modern multiculturalism

On Thursday 12 November, the renovated Muslim burial ground at Woking will be inaugurated. The walled structure, with its domed gateway, arches and minarets, was built during the First World War near the Shah Jahan Masjid – Britain's first purpose-built mosque – to receive the bodies of Muslim soldiers from Indian army hospitals along the south coast of England. It eventually housed 27 South Asian graves from two World Wars. We don't know much about these men but we do have their names and regiments – the poignant exception being “Abdullah”, killed on 16 December 1915 and listed simply as a “follower”. Gradually, the grounds fell into disrepair, and in 1968 the bodies were removed to Brookwood Cemetery nearby. Restoration was planned in 2012 with a grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund. The centrepiece will be an Islamic-style peace garden where one can reflect on the “sacrifices made by those servicemen” – and a reminder to Muslim youths of their “shared history” with the country and broader British identity.

Undivided India contributed more than one million men to the war effort, more than any other colony. Woking's is just one in a series of recent faith-specific memorials, and the Muslim counterpart to the Chattri Memorial on the Sussex Downs, which commemorates 53 Sikh and Hindu soldiers. Earlier this month, a new Sikh memorial was unveiled in the National Memorial Arboretum at Staffordshire.

One of the more lasting legacies of the war's centenary will be the recognition of its multiracial nature. In Britain, such commemoration has been marked by a general broadening, and a simultaneous sanitisation, of remembrance to take in the Commonwealth experience. The complex and sometimes contradictory motives and experiences of the South Asian, African and West Indian soldiers are often flattened into a paean of imperial loyalty and brotherhood eerily reminiscent of George V's call to the empire in 1914.

Colonial war memory is increasingly being reinvented as the grand stage on which to showcase the anthem of multiculturalism. Baroness Sayeeda Warsi set the tone in 2013: “Our boys weren't just Tommies – they were Tariqs and Tajinders too, and we have a duty to remember. Tommies and Tariqs fought side by side in the battlefield.” While Warsi is right to stress the diversity, the language of camaraderie veils much that was painful and unattractive. We have a historical duty to remember that, too.

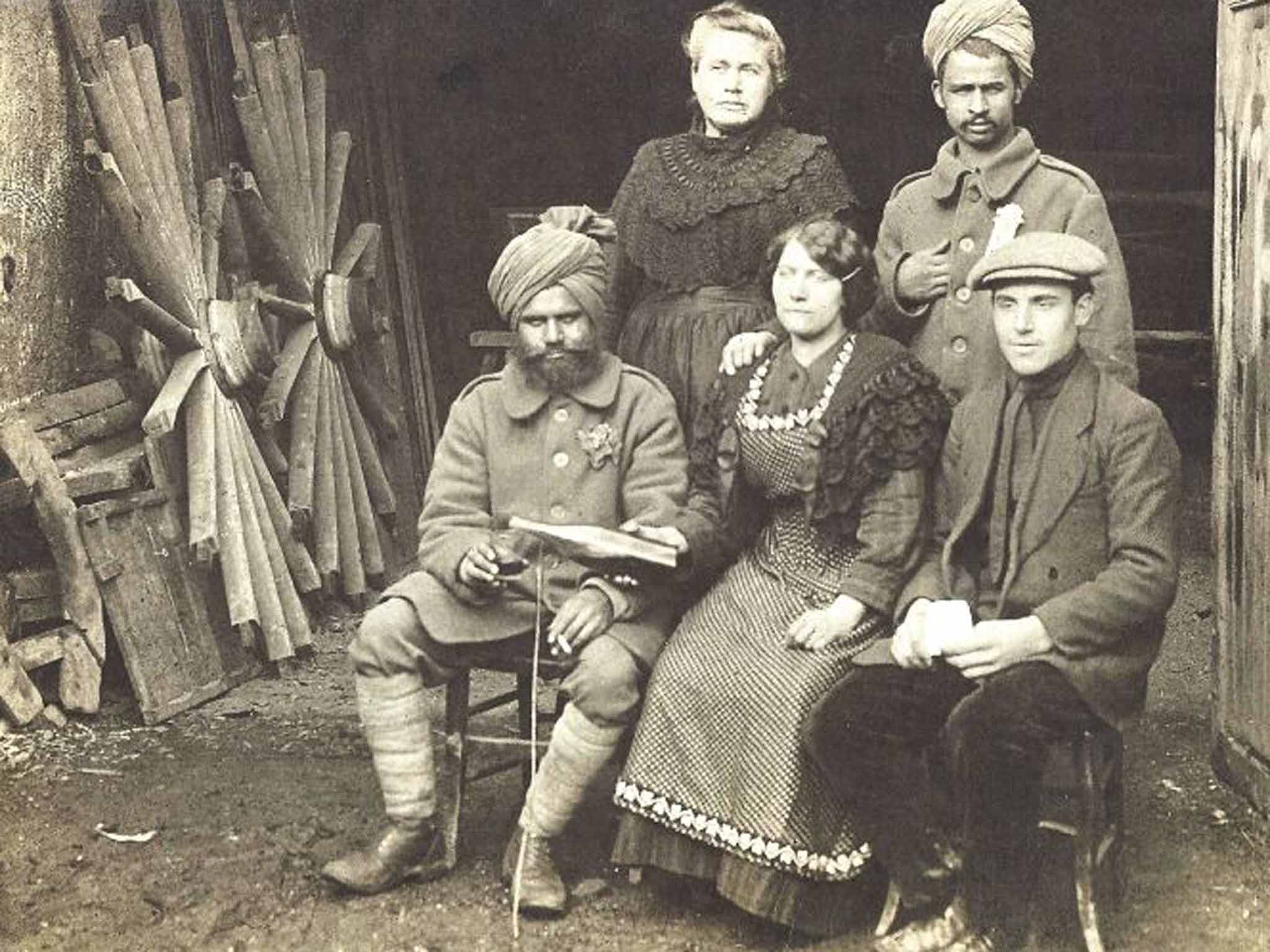

Of course, there are heart-warming tales of Indo-European friendship: British officers and Indian sepoys respected and admired each other; homesick sepoys referred to their French matrons as “mothers”; and when the latrine-sweeper Sukha, an untouchable, died and the Imam of Woking refused to have him, the Vicar of Brockenhurst stepped in and buried him in the local churchyard. Stories abound of sepoys risking their lives to rescue their British officers.

But in all my years of research, I have not come across a single example of a British soldier putting his life under fire for a sepoy. The colonial, military and racial hierarchies were all firmly in place. Indian soldiers, however senior, were always junior to the youngest British officer, and fences around the Brighton Pavilion Hospital kept the Tariqs and Tajinders apart from the Tommies.

The war was particularly difficult for the South Asian Muslims, with the Ottoman empire joining the war on the side of Germany in October 1914; a holy war was declared and the Muslims in the Allied army were promised “the fire of hell”. There were three mutinies in the South Asian Muslim units and the 15th Lancers refused to open fire on their religious brethren in Basrah in 1916. The Paris Peace treaty of 1919 and the dismantling of the Caliphate provoked widespread anguish. Mohammed Iqbal – the national poet of the future Pakistan – referred to the League of Nations as “thieves of grave clothes” set up for “dividing the world's graves”.

The contradictions are epitomised in the story of the Mir brothers. On a dark night in March 1915, Mir Mast, an officer, defected to the German side and went on an extraordinary jihad mission across Central Asia; his brother Mir Dast continued to serve gallantly, saved the lives of his British superiors, and got the Victoria Cross. Some soldiers had a touch of both: one prayed that “our King – God bless him – is going to win”, but inserted a separate note adding “Oh God we repent! Oh God we repent”. The South Asian soldiers were neither all imperial heroes nor martial robots. Many had volunteered to keep debtors at bay, and once in the Western front, they wrote back home: “For God's sake, don't come, don't come, don't come to this war in Europe”.

Commemoration by communities and military organisations often slips into a celebratory mode, as if these forgotten colonial soldiers can only be reclaimed as war heroes. True, some won the first Victoria Crosses for their countries; the majority, though, like the English Tommies, trembled and shat in their trousers as shells burst. If asked about imperial sacrifice, they would have pointed, like Wilfred Owen, to “the old lie” – they were only human in inhuman circumstances.

It is not enough merely to “remember”: we must choose what to remember and how.

'Indian Troops in Europe, 1914–1918' by Santanu Das (£24, Mapin) is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments