A History of the First World War in 100 Moments: A botched coup, sanctified by martyrdom

The failed uprising by Irish nationalists was an important event in the Great War – one that the British still fail to understand

Padraig Pearse was much condemned for the "blood sacrifice" he demanded of Irish republicans in 1916. He spoke of the "red wine of the battlefields" and was sneered at by pragmatic, unromantic Brits. Yet only a year earlier, our beloved Rupert Brooke was talking of the Great War warriors who "poured out the red sweet wine of youth". Blood sacrifice was a crazed European ideal at the time. And blood there was enough in Dublin at Easter 1916.

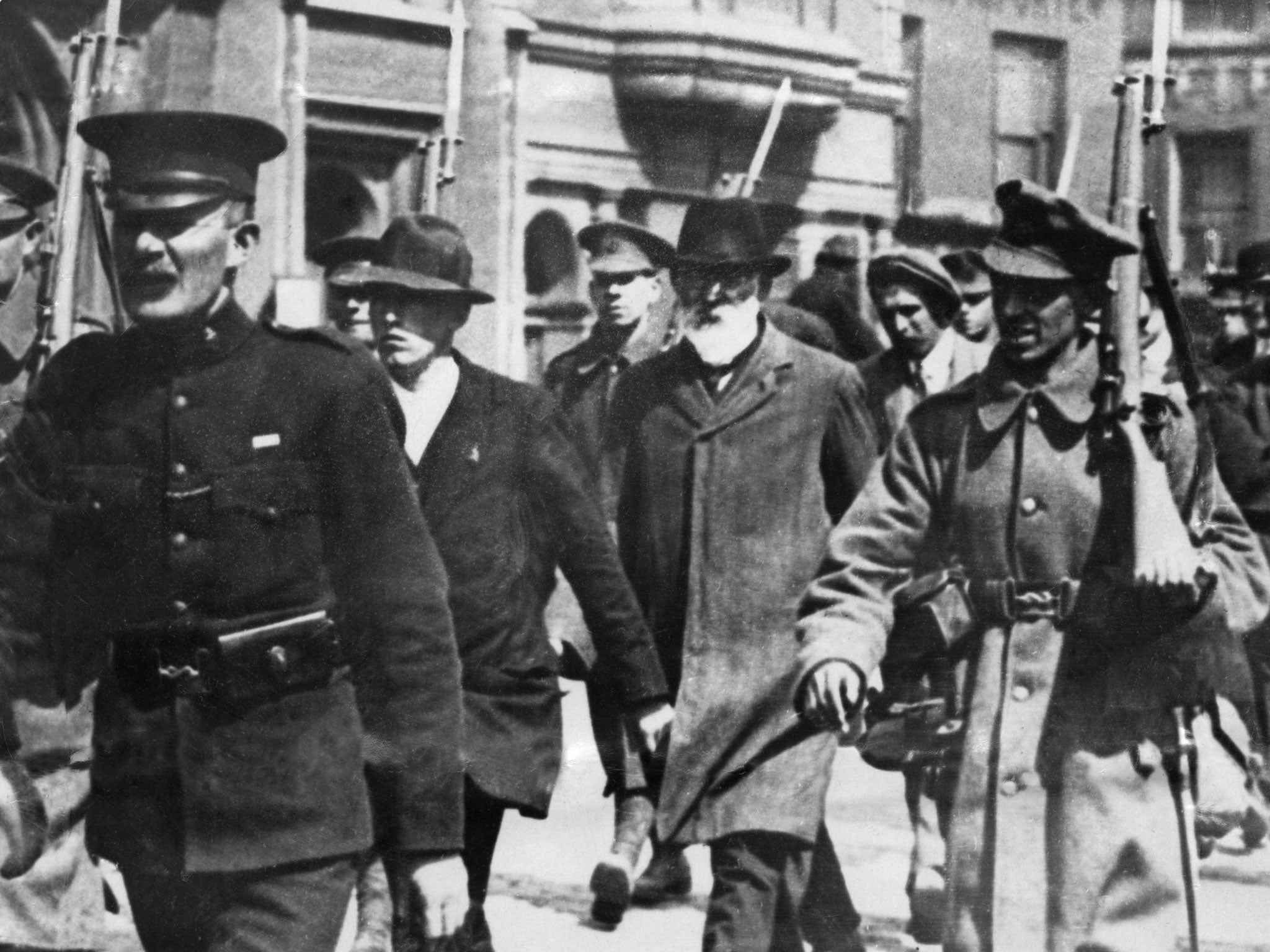

The legend: a group of 400 courageous Irish patriots took over much of the centre of Dublin and held out against overwhelming odds for six days before surrendering, their ringleaders – including Pearse – executed in short order by a British Army which thought nothing of shooting its own soldiers at the stake in France.

The truth: it includes much of the legend. The Irish rebels were courageous. The British used heavy artillery and a gunboat on the Liffey with First World War promiscuity. But the insurgents' planning was abysmal, their rising cancelled elsewhere in the country. By the time they surrendered amid the ruins of Sackville Street, armies of Dublin looters had swarmed into the wreckage amid Irish cries for the insurgents' punishment. The Irish Independent successfully called for their deaths. The execution of 15 of the leaders was more important than the Rising, the British typically turning rebellion into martyrdom.

The only unmentionable: all of the 16 policemen killed by the insurgents and 22 of the 116 British Army fatalities were Irishmen. Indeed, the first engagement of the Rising was fought between Pearse's irregulars and the Royal Irish Regiment. Irishman was fighting Irishman. The dead of both sides still lie in Dublin, one cemetery containing servants of the Crown beneath Commonwealth war grave headstones, the other worthy three years ago of a bow of the head from Her Majesty.

If you look up the 1916 executions in the National Archives at Kew, you'll find them filed with records of death sentences for cowardice for British soldiers in France. For the British, the Rising was just another – albeit infinitesimally small – battle in the Great War. After all, did not Pearse's proclamation of the Republic and its reference to "gallant allies in Europe" – obviously, the Germans – make it so? Yet Britain's later attempt to extend conscription to Ireland only added to popular Irish revulsion at the executions. Within six years, the UK would lose most of Ireland.

But if the Rising symbolised Irish independence, it also gave rise to a certain folly in Britain: the idea that the Irish were, deep in their hearts and despite all evidence to the contrary, still British. Misled they may have been by the Wolfe Tones and the Pearses – crushed, according to Punch magazine, by their own laziness and by alcohol – but the Irish people, so this pernicious legend would have it, never really desired independence from the motherland. Why else were John Redmond's 200,000 Irishmen still fighting for the British in France and Belgium? Even in the Second World War, Churchill – convinced that true Irishmen were on Britain's side – believed that Eamon de Valera's neutral Ireland was "at war, but skulking".

Thus a rising for freedom was translated as treachery; hence the little war crime in 1916 when the British Army slaughtered 15 of the more than 300 rebels and civilians who were to die in the Easter insurrection. The rebels, too, shot recalcitrant civilians. But hence, too, the bloody record of British military operations in Northern Ireland just over half a century later. The innocent 14 dead of Bloody Sunday in 1972 were shot down, ultimately, as rebels against the Crown. Irish President Michael Higgins may have interpreted his state visit to the Queen this year as recognition – at last – of Ireland's independence. But the British, I fear, thought they were welcoming the Irish back to their natural "home". Untrue. Reality must be respected.

Difficult, though, in the aftermath of 1916. One of the young girls killed in the Rising was 15-year old Eleanor Warbrook from a Protestant family, shot in the jaw in Dublin on 24 April. Her brother Thomas was to die five months later – as a British soldier in Canadian uniform at Vimy Ridge.

Tomorrow: A U-boat sinks a steamer

The '100 Moments' already published can be seen at: independent.co.uk/greatwar