Adrian Hamilton: Breaking with the past is key to Turkey's future

World View

With all that was going on in Europe at the time, the Dersim massacre of the Tunceli Alevi in eastern Turkey between 1937 and 1938 aroused little attention. But it was a fearful crime nonetheless. A total of 13,806 people, many of them civilians, were killed, according to documents released last week by Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan. As many as 22,000 were deported from the area, according to the musicologist Hasan Saltuk, who has a book on the subject coming out in May. In style, in brutality and in intent, it was reminiscent of the much bigger killings of the Armenians at the end of the First World War.

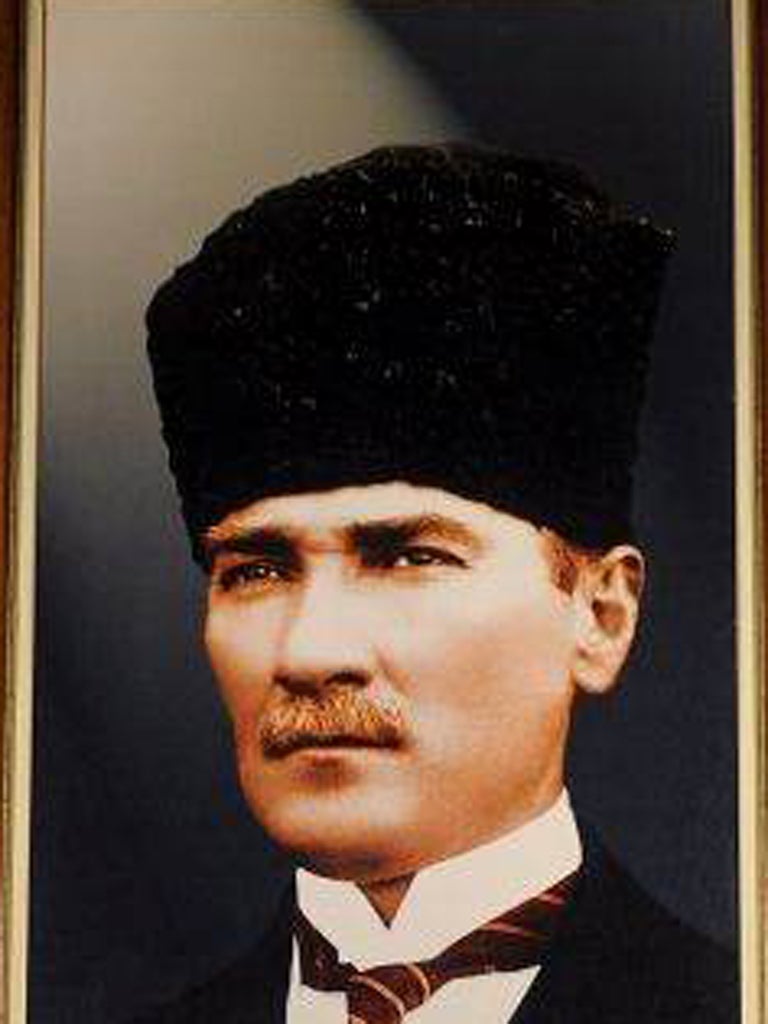

It's hard to overestimate the significance of the decision to release these documents and for the Prime Minister to publicly "apologise" for the action. Ever since their defeat in the First World War and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the Turks have been living under the narrative created by President Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, the "father" of the nation – that of a modern westernised secular state which had rejected its past, abandoned its Muslim status and had reformed itself into a centralised nation. Even today it is a crime, punishable by imprisonment, to speak ill of him.

But that is what, by implication, Erdogan is now dong, although he's too shrewd to do so openly. The opposition, the Republican People's Party (CHP), has been quick to dismiss the move as a political ploy to put them on the spot as it was the CHP – the only party allowed at the time – which could be held responsible. And there is undoubtedly truth to its charge. After 12 years in office, and successive popular wins at the polls, Erdogan shows growing impatience with any opposition, whether from the press or from other parties. He and his Islamism-based Justice party clearly want a complete break with the country's secularist constitution and its military-dominated post-war history.

By directly implicating Ataturk himself in this affair, however, the government is also breaching a whole wall of secrecy and denial about the past. With the Dersim documents out in the open, do we now move to open admission of state responsibility for the Armenian genocide? Does Ankara accept what it has done to the Kurds within its territories?

With the centenary of the Armenian massacres due in 2015, the opportunity for a grand gesture of responsibility is clearly there. It's what traditionalists fear, concerned that, in raking up the past, the government will now release the forces of fragmentation of the state, and liberals dearly wish for, eager to see the country face up to its past. Even those who distrust Erdogan's religious aspirations nevertheless welcome the moves to dismantle the judicial-military network which has dominated the country since the last war.

One of the truly great figures of the 20th century, Ataturk managed to get a country in the ruins of a once-powerful past to come to terms with its defeat and face the future. No other imperial power managed that feat. One asks whether the US now or Britain can do it as effectively. But it was at a cost to tolerance, to the minorities and to freedom.

Nearly a century later, we are in a very different world in which a resurgent Turkey is laying claim to a regional influence and an example of moderate political Islamism which it has not seen since the Ottoman days. For the outside world, it is its foreign policy that fascinates, its break with the US and its support of the overthrow of the regimes of Libya and Syria. But it is the story of change within the country which is just as fascinating and uncertain. Nowhere does history matter as much as in the Middle East. In confronting its past Turkey is now preparing itself for a different future.

The ICC is a white man's idea of justice imposed on the developing world

Laurent Gbagbo, who was flown from Ivory Coast to The Hague yesterday, is the first former head of state to face trial by the International Criminal Court since its founding 10 years ago. A moment of rejoicing, it could be said, by those who seek to make the Court the place where murderous dictators are brought to account.

I wish I could share their optimism. Over the decades, when we have had to watch tyrants act with impunity, there has been an ovewhelming sense that they shouldn't get away with it, that there ought to be a system of justice that makes them aware of the consequences of their misdeeds – if not at home then before the international community.

But the end result is a court which, by the nature of its centre and staffing, has become something of a white man's idea of justice imposed on the developing world. Nearly all the proceedings initiated by the Court have been against individuals in Africa. Too often it is seen as a means of new rulers getting rid of the problem of managing deposed old ones. That's how it seems with Gbagbo.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies