Adrian Hamilton: To settle Syria you need an accord between its neighbours

World View: The Syrian revolt clearly presents the Iranians with a problem of loyalty

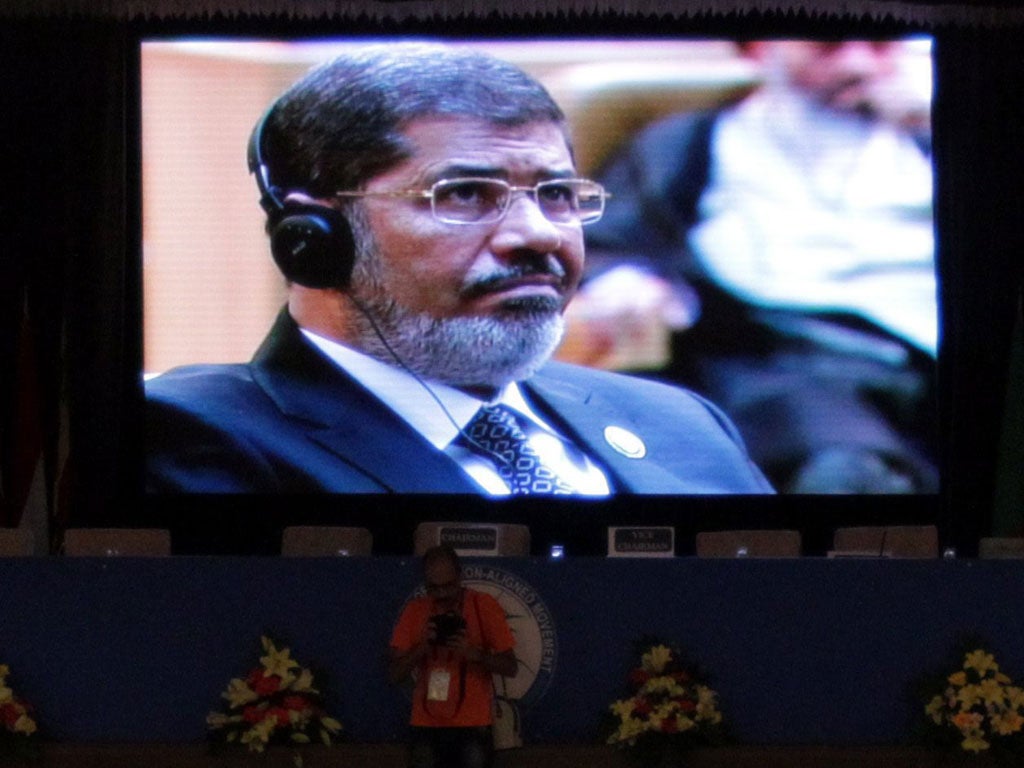

The good news for the Iranian government is that President Morsi has come to the Non-Aligned Movement meeting in Tehran, the first Egyptian president to visit the country in more than 30 years. The bad news is that he came to condemn the Syrian government for its actions and promptly caused a walk-out of Iran's long-time ally as a result.

Such, as ever, are the complexities of Middle East politics. But before anyone in the Foreign Office or US State Department gets too excited by the thought of Morsi raining on Tehran's NAM parade, they should consider the shifting powerplay in the Middle East and what it holds for Western policy.

The Egyptian revolution has certainly brought in a new Islamist government which needs Western money help in rebuilding the country. But Morsi is no Mubarak. To those who dismissed him as a grey man or just a front for the Islamists, he has taken charge of the country with surprising energy and speed.

He arrived in Tehran this week after a two-day visit to China. Next, he plans to go to Brazil and Latin America. Egypt, he is saying, is back in the international business but, unlike the days of its predecessor, it is determined to act as an independent voice of its own. Turkey – also with a Muslim government – is doing the same.

Which leaves Iran as the third independent power in the region. The Arab Spring in general, and the Syrian uprising in particular, have undoubtedly caught it out. On the one hand, its revolutionary origins and its anti-authoritarian rhetoric should put it on the side of the overthrow of pro-Western tyrants.

On the other hand, its close ties with Syria and its own brutal suppression of dissent makes it anxious that the revolutions sweeping the Arab world will unseat its allies and diminish its influence in the region.

It isn't only Syria which has embarrassed its proceedings at the Tehran summit. It also got caught up in the politics of Palestine when the representatives of the official Palestinian government declared they would not attend if Iran's ally in Hamas was invited.

Iran isn't foolish. It has managed the Palestinian problem by not inviting the Hamas leader as an official representative at the summit, but extending a personal invitiation for him to visit Iran's President Ahmadinejad.

It is also going to considerable lengths to play the good host in Tehran to the Saudis and other so-called hostile Gulf monarchies. Ayatollah Khamenei, Iran's supreme ruler, also received the former US assistant secretary of state, Jeff Feltman, who now serves as the UN undersecretary for political affairs.

The Syrian revolt clearly presents Iran with a problem of loyalty. The alliance with the Ba'athist regime in Damascus has been a close one and Iran's security forces are undoubtedly helping the regime in its efforts to suppress the revolt. But if the rebels clearly started to win, it is doubtful that Iran would intervene directly to save President Assad. It doesn't want a pro-Western government in Damascus, but it doesn't require a Shia one. If the Syrian revolution were to produce an independently minded Sunni government on the lines of Egypt and Tunisia, Tehran would work with, not against, it.

At the beginning of the meeting in Tehran, the Iranian government promised to produce an "acceptable and rational proposal" for the Syrian conflict. It hasn't materialised, which is no surprise given the difficulties. But – just as in Afghanistan – any settlement in Syria needs the active support of the neighbours. The West's policy of isolating Iran is only making that more difficult.

Iran and the moral side to nukes

Ayatollah Khamenei's declaration at the Tehran summit that Iran continued to seek nuclear technology but would never develop nuclear weapons was greeted with the usual cynicism, if not downright dismissal here. But why?

Whatever else the Islamic regime of Iran today may be – and it is pretty awful in its treatment of its opponents at home – it does attach great importance to the tenets of the original revolution. Ayatollah Khomenei, the father of the revolution, declared nuclear weapons an anathema.

That Iran wishes to master the technology of nuclear power in all its forms is not in doubt. It would be mad not to given the open threats against it. But it would still be difficult for any government there to develop the weaponry, even in secret, in view of its public principles.

It is a signatory of the Non-Proliferation Treaty governing its activities and, whilst it has not always allowed the International Atomic Energy Agency's inspectors access to all the sites and the information they have demanded, it has not (unlike Saddam Hussein) thrown them out.

What it would like, of course, is to lead a general shift towards the NAM's stated aim to get rid of all nuclear weapons by 2025, including Israel's. But there's the rub…

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies